One of the most significant oil and gas discoveries ever made in the United Kingdom Continental Shelf (UKCS).

The Brent Field, one of the most significant oil and gas discoveries ever made in the United Kingdom Continental Shelf (UKCS), celebrated its 40th anniversary in November, 2016. Having produced nearly 4 Bboe and given its name to one of the industry’s major crude oil pricing benchmarks, this aging giant is preparing to close down.

Discovered in 1971, the Brent field opened up the Northern North Sea sector of the United Kingdom continental shelf (UKCS) and was one of the first UK fields to come on stream. It lies about 180 km north-east of the Shetland Islands, close to the border with Norway, and when discovered was estimated to contain 1.8 Bb recoverable oil. Since that time it has produced over 2 Bbo and 5.7 Tcf, and at its peak in the early ’80s it was producing more than 0.5 MMbopd, supplying 13% of the UK’s oil and 10% of its gas needs. Since its discovery, Brent has been a 50:50 joint venture between Esso and Shell, with the latter as operator.

This article first appeared as the lead story in Vol. 14. No. 2. (see Cover Photo, opposite) For more information about getting a hard copy of our magazine, see the ‘Print subscription’ feature at the top of this page.

Classic North Sea Petroleum System

Brent proved to be the archetype for many of the fields in the area: a tilted fault block unconformity trap with bounding faults that allowed migration from the Kimmeridge Clay, the most prolific hydrocarbon source in the North Sea.

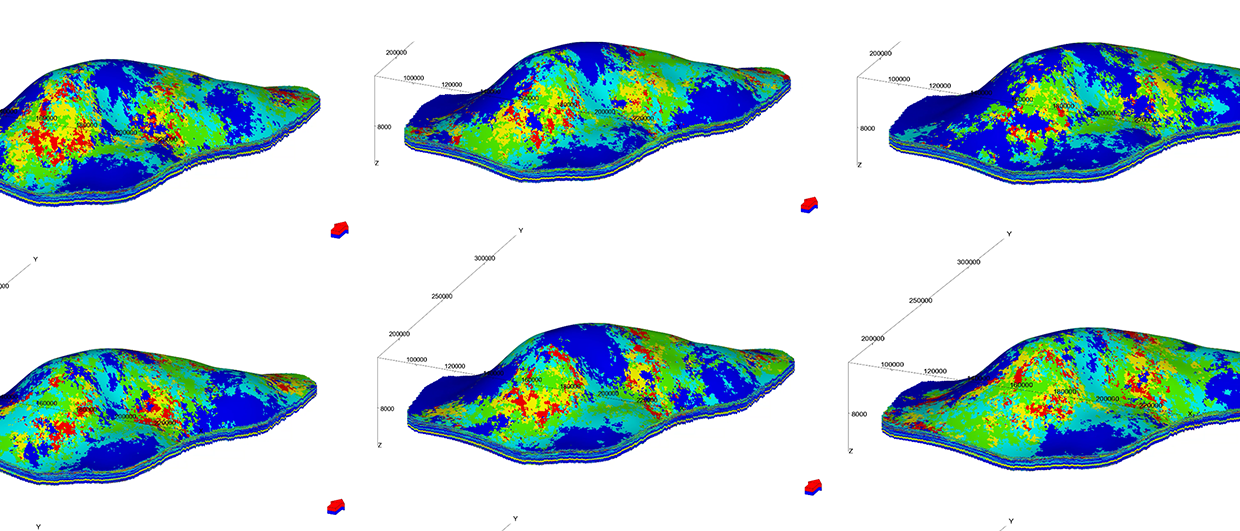

The Brent Field. (Source: Shell)

The field, approximately 16 km from north to south and 5 km across, is located in the central part of a 65 km-long fault terrace on the western margin of the Viking Graben, the northern extension of a 1,000 km rift system extending northwards from the Central North Sea Graben. Two major east-west oriented faults divide the northern area of the field into a wide graben and horst feature, creating three separate production areas, whilst a structurally complex zone along the crest of the field, known as the Brent and Statfjord Slumps, forms a fourth production area.

There are two main reservoirs. These are the Middle Jurassic Brent Group, which is, in economic terms, the most important hydrocarbon reservoir in north-west Europe, and the Lower Jurassic/Triassic Statfjord Formation. The latter comprises an upwards-coarsening fluvial sandstone sequence, ranging in thickness from 270m to 300m from south to north. The mud and siltstones of the Dunlin Group separate it from the approximately 240m-thick interbedded sandstones, siltstones, shales and coals of the Brent Group, which were deposited within a shallow marine and coastal plain environment. The Group consists of five formations, known as Broom, Rannoch, Etive, Ness and Tarbert – hence the name.

The hydrocarbons are trapped in a simple fault-bounded, monoclinal structure, dipping about 8° to the west, with in addition some crestal truncation unconformity traps caused by the slumping. The Statfjord Formation is also trapped in the east by faulted Lower Cretaceous mudstones. Seal is provided by a series of mudstones or calcareous mudstones and marls overlying the unconformity surfaces.

The main source rock is the Upper Jurassic Kimmeridge Clay formation, migrating from both the Viking Graben and the East Shetland Basin, where it has an average TOC of 5.6%. It could be also migrating vertically up the steep, faulted eastern scarp or along the shallower western dip slope of the block, and there is also evidence for lateral migration along the major fault terrace.

Schematic cross-section over the Brent field. (Modified after Taylor et al., 2003)

Highest Performing North Sea Field

To access the light, sweet crude which is now an industry benchmark, four platforms – Brent Alpha, Bravo, Charlie and Delta – were constructed between 1975 and 1978 in a line running roughly 10 km south-south-west to north-north-east over the field (see the schematic image at the end of this article).

Brent B, the first Brent platform to be commissioned, was built in Stavanger, Norway and towed out to its location on the field in August 1975. (Source: Shell)

This was a major engineering feat, since at the time Brent, in water depths up to 150m, was one of the deepest offshore oil fields in the world. Brent Alpha is a steel jacket, while the others have concrete gravity base structures weighing more than 300,000 tonnes each. From the seabed to the top of the platforms, they stretch up over 300m, including the ‘topsides’, which has the equipment for drilling, producing and processing oil and gas, as well as the accommodation block and helipad. Brent Delta, for example, could accommodate 161 people on board at any one time.

A fifth installation, the floating Brent Spar, which served as a storage- and tanker-loading buoy, was constructed in 1976, loading the first tanker of crude from the field in December the same year. In the late ’70s three enormous gas compression modules, containing what were at the time the world’s largest offshore reciprocating compressors, were built to re-inject gas into the reservoir. Initially transported by tanker, from 1982 most of the oil was pumped via a 147 km-long pipeline to Sullom Voe in Shetland, while gas was piped 450 km to Scotland.

As oil output began to decline in the 1980s, Shell created a development plan designed to switch the main production from oil to gas, because the high solution gas: oil ratio meant that substantial gas reserves remained in situ. The Brent redevelopment project cost £1.2 billion and involved depressurizing the entire reservoir in order to release solution gas from the bypassed and remaining oil and making extensive modifications to three of the four platforms, thus extending the field’s life beyond 2010. In 2000 Brent was externally benchmarked as the highest-performing North Sea field, and by 2001 it was producing record levels of gas.

Brent Charlie in high seas: the rough weather in the Northern North Sea is one of the many challenges to be overcome in planning the decommissioning of the Brent field. (Source: Shell)

Detailed Planning Required

When the Brent Field was discovered, it was expected to have a total life span of 25 years. With careful management, continuous investment and the use of cutting-edge technology, that has now been extended to 40 years. But with an estimated 99.5% of the economically recoverable reserves in the field produced, it is time to commence the long, complex and technically demanding task of decommissioning.

Production from Brent Delta stopped in December 2011 and all 48 of its wells have now been plugged and abandoned. Both Alpha and Bravo ceased producing in November 2014, while production from Charlie is expected to finish within the next few years.

Decommissioning fields and pipelines in the UKCS is a tightly defined regulatory process overseen by the government’s Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (BEIS). It requires that decommissioning is carried out in a way that is technically achievable and economically responsible, while having minimal impact on the environment or involved communities. The safety of those working on the project is of paramount importance.

Brent oil and gas production. (Source: Data source: UK Oil and Gas Authority)

The decision to decommission a field is therefore not an easy one, and Shell and Esso only took this after many other options of how to re-use the platforms – from carbon capture and storage facilities, to wind farms and even offshore prisons and casinos – had been considered. However, after consultation with BEIS, it was decided that the age of the infrastructure, distance from shore, the lack of demand for re-use, as well as the cost of modernizing the facilities, put alternatives out of the question; decommissioning was the only viable option.

Shell began the long-term planning of this task back in 2006. From early in the process this included an independent review group which objectively looked at all the scientific and engineering methods which could be required, involving many meetings with stakeholders. Much had been learnt from the decommissioning of the redundant Brent Spar 20 years ago, when both the operator and the UK government had determined that the safest place to dispose of it was deep in the Atlantic, but an outcry from the public, activists and several European countries halted that plan. Eventually, in 1999, after a long series of discussions and many imaginative suggestions, the solution was to use the lifted, cleaned and broken up installation as the base for a ferry quay in a Norwegian fjord. This proved effective but far more expensive than originally planned and many valuable lessons, particularly on engaging with communities and the recycling of materials, were learnt from the experience.

Recycle or Leave?

Shell have now submitted two detailed decommissioning programs to BEIS, one to cover the Brent platforms and the 154 wells, and the other dealing with the pipelines and other subsea infrastructure. Plans must include the removal to shore and subsequent recycling of the platform’s topsides, the recovery of associated debris from the seabed and the removal of trapped oil, among many other issues.

The concrete pillars supporting Brent B, C, and D will probably be left in situ. (Source: Shell)

Contracts to remove, transport, reuse and recycle the platform topsides have been awarded and include the use of a giant vessel, Allseas Pioneering Spirit, which at 382m long and 124m wide is the largest construction vessel ever built (see Decommissioning in the North Sea). It will lift the topsides in one go and transport it to shore. The target is to recycle at least 97% of the topsides material.

For the base of the platforms, the plan is to cut the upper portion of the Brent Alpha steel jacket and recycle it, but working out how to deal with the heavy concrete gravity base structures of the other platforms was less easy. Each base comprises a cluster of concrete storage tanks and not just their weight but their contents had to be taken into account. As well as containing sand ballast, they had been used for oil storage, but assessing their contents was difficult since they are deep underwater and have very thick walls. Help came from a surprising source – NASA. Special gold-painted ‘sonar spheres’ the size of a bowling ball were designed to access the cells and take sonar images of the cell sediment so that Shell could identify their physical characterization.

The final recommendation, which has yet to be officially approved, is to leave in place the giant concrete structures, as well as the Brent Alpha footings, the drill cuttings and cell contents, due to the technical and safety issues as well as the huge cost involved in attempting to recycle them. Although it is difficult to predict how and when these structures will eventually collapse, studies suggest that the visible part of the legs will remain in place for up to 250 years, the section under the sea may last another 300 to 500 years, while the oil storage cells are expected to remain largely intact for at least 1,000 years. Pipeline infrastructure in the field includes 28 lines totaling approximately 103 km and thousands of tonnes of steel, concrete and rocks, as well as several subsea structures. A range of options is being considered for the pipelines, depending on their age and condition, including complete removal, cutting and sealing the ends, leaving in place with a covering of rock or trenching and burying them.

Complex Project

Given the harsh marine environment of the Northern North Sea and the complexity and relative age of the structures, retiring the Brent field was always going to be a challenging technological project, requiring careful implementation and considerable innovation, which is expected to take until the mid-2020s to complete. As one of the first major decommissioning undertakings in the world, many eyes will be on this project and despite the steep learning curve it is expected to set an example for the industry to follow.

Over its 40-year life, the Brent field has generated more than £20 billion in tax revenues (in today’s money), delivered a significant amount of the UK’s energy needs, provided tens of thousands of highly skilled jobs and considerably increased technological knowledge and competence within the oil and gas industry throughout the world. We have much to thank it for.

Acknowledgement

Many thanks to Shell for assistance with this article.

References

Taylor, S. R., Almond, J, Arnott, S., Kemshell, D. & Taylor, D. The Brent Field, Block 211/29, UK North Sea, Geological Society, London, Memoirs 2003, v. 20, p. 233-250

http://www.independent.co.uk/news/business/news/shell-declares-end-of-pipeline-for-brent-oilfield-10019486.html

http://www.shell.co.uk/sustainability/decommissioning/brent-field-decommissioning/

Struijk, A. P., & Green, R. T. The Brent Field, Block 211/29, UK North Sea, 1991. Geological Society, London, Memoirs v. 14, p. 63-72

Morton, A. C., Haszeldine, R. S., Giles, M. R. & Brown, S. (eds), 1992, Geology of the Brent Group. Geological Society Special Publication No. 61, pp. 1-2.

UK Oil and Gas Authority: www.ogauthority.co.uk/decommissioning

Further reading from the GEO ExPro Archive

Decommissioning in the North Sea – GEO ExPro talking to Greg Coleman. This article appeared in Vol. 14, No. 2

Is There a G in Decommissioning? by John Simpson and John McNab, Exceed Ltd. This article appeared in Vol. 14, No. 2

Endgame for the North Sea? by Will Thornton. This article appeared in Vol. 12, No. 6

A Golden Celebration for Silver Seas by Will Thornton. This article appeared in Vol. 12, No. 4