In late Permian times, around 255 million years ago, the area that now occupies the North Sea, parts of Britain and the area stretching from the Netherlands to Poland, formed an amalgamation of deserts and ephemeral fluvial systems that ultimately drained into a playa lake. This is what is currently called the Southern Permian Basin.

It is the time of Pangea, when all continents were still welded together. The Southern Permian Basin was far from the open ocean, with the closest connection probably being situated in the north towards the Arctic. In this setting, whilst subsidence did take place with the resulting deposition of the typical Rotliegend facies associations, the area gradually “sunk” below global sea level.

So, when Pangea started to break up again in late Permian times, sea water that probably originated from the north could make its way into what must have become the equivalent of a nearly dried up pool. The aeolian landscape of the Southern Permian Basin drowned and turned into a shallow sea.

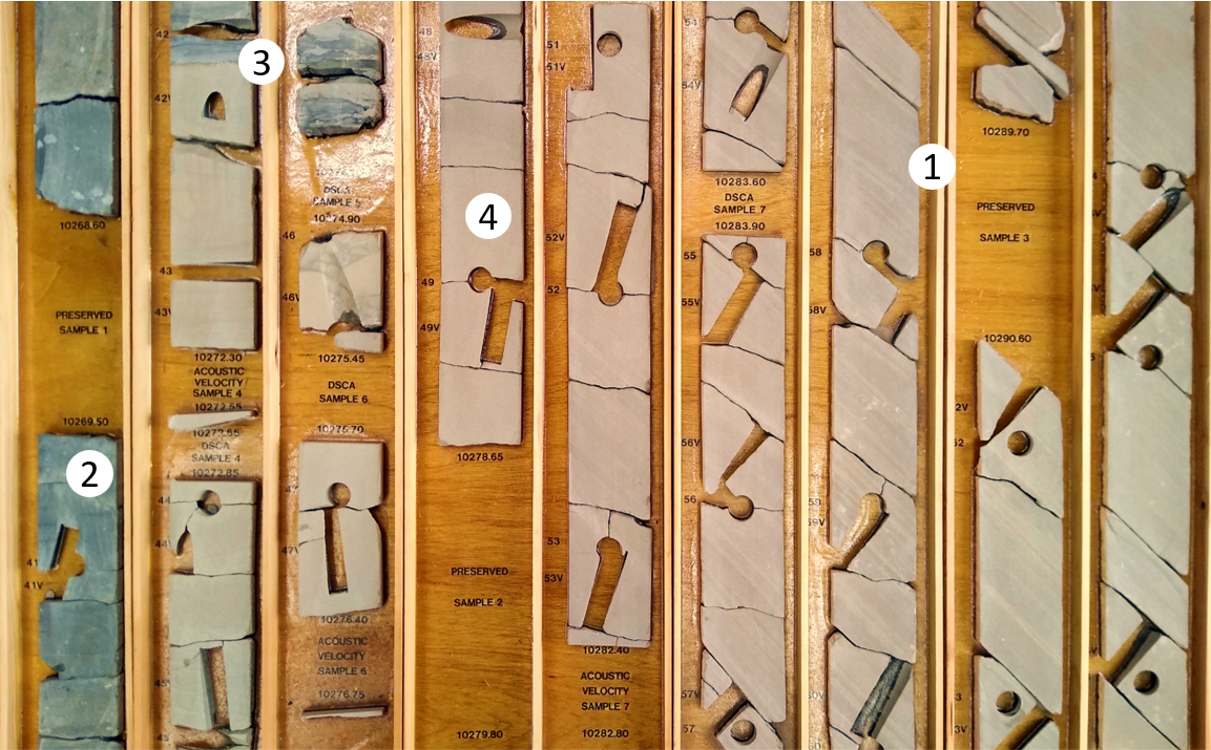

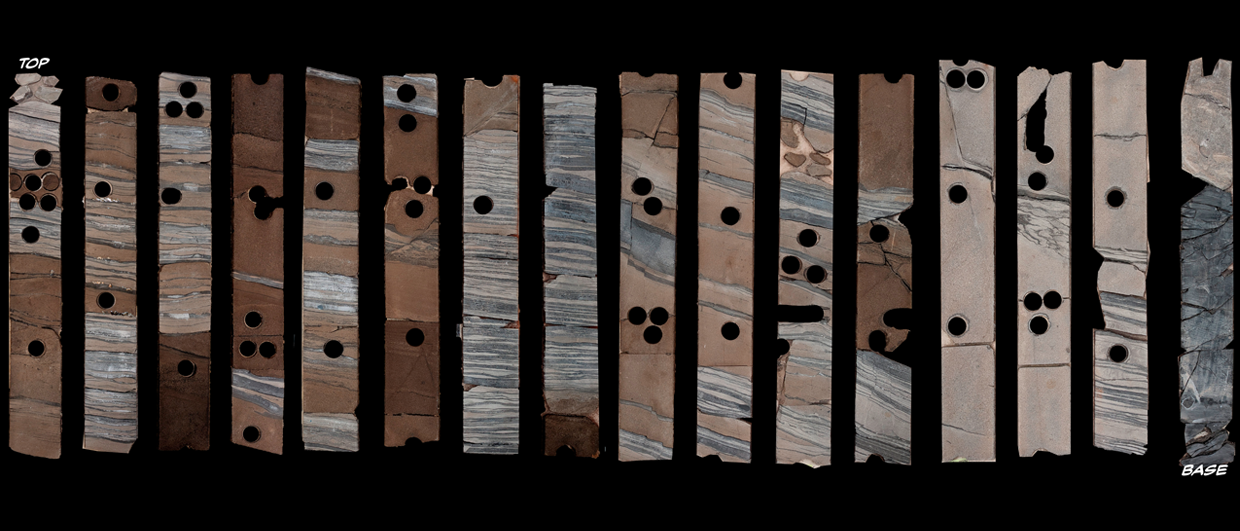

This event is recorded in the cored section shown above. It is from development well 48/11b-A5 in the Pickerill field in the UK Southern North Sea and shows the transition from parallel laminated dune sands on the right to the darker Zechsteinkalk to the left. In many places across the basin, the so-called Kupferschiefer black shale is directly overlying the Rotliegend sands. Here, it is lacking, which is probably because of the peripheral location of the well with respect to the basin boundaries (see map).

This peripheral setting is probably also the reason why the Rotliegend-Zechstein transition was cored in the first place, as the aeolian succession is relatively thin in the area. In order to ensure that the Rotliegend would be fully cored – which is where the gas used to reside – drillers must have decided to start coring just before the expected top Rotliegend.

Sections such as these tell the fascinating story of the geological history of the wider North Sea area and form a reminder that under certain geological circumstances, environmental changes can happen within “split seconds” of geological time.

The cored section used for this article is held by North Sea Core CIC, an organisation that takes delivery of redundant core from the UK Oil and Gas Industry in order to save it from going to landfill and make it available for the wider geological community.