“ In some ways, knowing the reservoir storage capacity of a CCS project is even more critical than knowing the size of the same reservoir prior to gas production,” said Alan Johnson at the start of his presentation at the Aberdeen Formation Evaluation Society.

This is mainly because storage contracts will often need to be signed before FID for a CO2 capture project is considered. Of course, this is all still a bit theoretical, as there are not that many examples of CO2 storage projects that have experienced FID, but the reasoning makes sense. At the end of the day, a chain of investments on the capture side is heavily dependent on the ability to store the CO2 at the downstream end of the line.

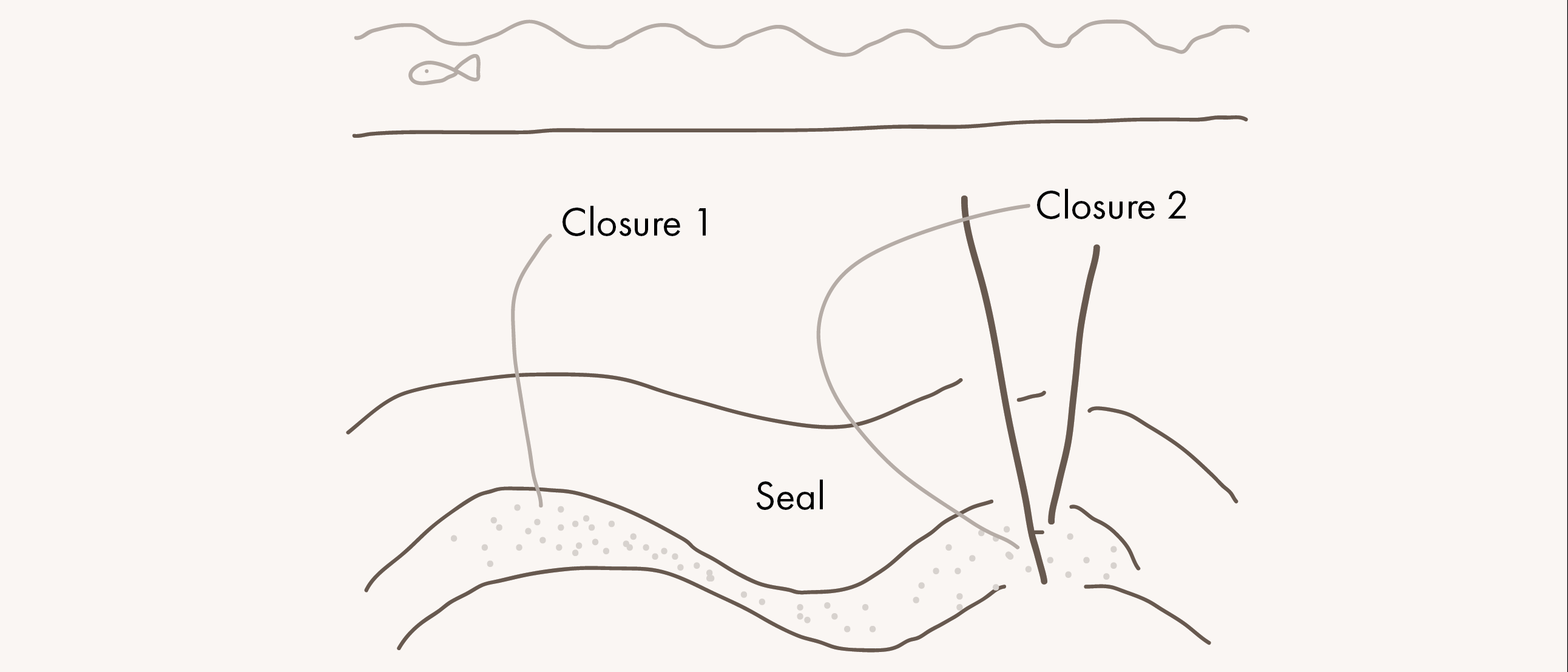

For that reason, Harbour UK asked Alan to carefully assess the subsurface data of the Viking A depleted Rotliegend reservoir in the UK Southern North Sea, with the main underlying question of how reliable the core and wireline data are as input to calculating its ultimate storage capacity. The Viking A field is one of the earliest discoveries made in the UK North Sea, 1969 to be precise.

Having started his career in petrophysics in 1974, just a few years after the first major gas discoveries were announced, it is easy to see why Harbour asked Alan to carry out this job. He worked with the data types used back then and knew about the uncertainties, which is surely an advantage when revisiting it 50 years later.

One of the main questions centred around the reliability of porosity data from core measurements carried out in those early years. Often, core reports from back then do not accurately describe the ways the cores were dried, which might have had implications for the amount of water still in the core at the moment a porosity calculation is made. For instance, statements such as “Thoroughly dried” are a common occurrence, which clearly leaves room for speculation at which temperature the cores were actually dried.

However, despite these uncertainties, a careful analysis of various ways in which cores were prepared for analysis indicated that the drying methodology was not of detrimental effect on the reliability of the data. Why is that?

“The Rotliegend reservoir sands are quite forgiving,” concluded Alan at the end of his presentation. As the sands are often quite well sorted and without significant clay content, he concluded that the drying method has ultimately had little effect on the reliability of the porosity data. This is good news when it comes to using old data to calculate storage space in this area. However, if it would have been another reservoir with more of a mix of lithologies, this certainly would have been a little harder to conclude.