A perfect energy storm has been brewing during 2021. A cold winter around the world in 2020 saw gas demand rising, severely depleting gas stores. Those reserves would normally be replenished over the summer, but gas output has declined because many major producers have been catching up with maintenance postponed during the Covid-19 pandemic lockdowns. This has meant natural gas storage in Europe is currently low at around 76 percent, according to Gas Infrastructure Europe. This time last year, it was at around 95 percent.

A Perfect Energy Storm

To add to this, calm weather reduced the amount of electricity generated by wind power, especially for countries like the United Kingdom and as a result, wholesale gas prices have more than quadrupled over the last year. This rise in global wholesale gas prices has been felt across all of Europe and countries that rely heavily on imported gas, such as Italy and Spain, have been particularly hard hit. Their governments have directly cut gas prices and raised taxes on energy company profits to try to address the situation.

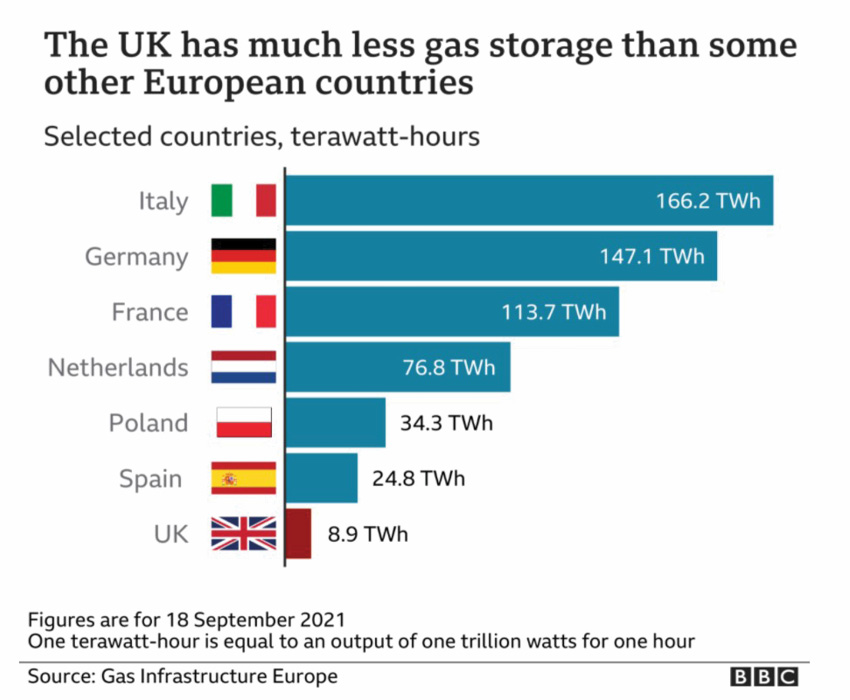

For the UK, as one of Europe’s biggest consumers of natural gas (over 85% of homes using gas central heating, and with around 30% of electricity generation from gas), the challenge is clear. Given the current supply issues, a harsh winter in Europe dramatically increasing demand could have very significant consequences.

Flexing Supply Muscle?

Russia has the largest natural gas reserves in the world (47,800 Bcm) and supplies much of the gas used by Europe (around one-third of the EU’s gas consumption) and by 2035, the EU will need to import about 120 Bcm more gas per year. In terms of supply, Russia and Europe are somewhat co-dependent in that Europe is Russia’s main market, and as long as its gas remains competitive, Russia is likely to remain Europe’s main supplier and demand for gas is expected to continue, owing to its lower CO2 emissions compared with coal and oil. This suggests that in the medium term at least, the EU will need to import more gas, especially as the European production outlook for the major gas producers such as the Netherlands and UK, as well as Norway, are falling.

How much Russian gas Europe imports in the future will depend on competition between Russian gas and other sources such as LNG. Suppliers from many different countries now compete to supply the EU internal market. In addition to import pipelines, there are currently 22 LNG terminals in the EU which can receive LNG from anywhere in the world. With a capacity of 216 Bcm, these terminals could import 50 percent of the EU’s current demand, but they are currently only utilised at some 27 percent of capacity.

When Russian President Vladimir Putin indicated in early October that Russia could be ready to ease Europe’s energy crisis, the markets breathed a collective sigh of relief, but some European politicians and experts are concerned that Russia is attempting to pressure regulators to approve the newly completed Nord Stream 2 pipeline, which will have the capacity to meet about one-third of the EU’s import requirement. Other experts argue that Russia doesn’t have sufficient spare gas and is trying to fill up its own storage facilities ahead of winter.

Pipeline Politicking

Nord Stream 2 will deliver gas to Europe from the vast natural gas field Bovanenkovo, located in Northern Russia’s Yamal Peninsula, which holds some 4.9 trillion cubic metres of gas reserves and is expected to produce gas until at least 2028. This field alone holds more than twice as much gas as the total proven reserves of the EU (1.9 trillion).

The pipeline will travel 1,230 km through the Baltic Sea, starting from the Russian coast at Narva Bay and reaching landfall near Greifswald in Germany. It will run roughly parallel to the existing Nord Stream pipeline.

Some experts argue that Putin wants to pressure the European Union to rewrite its gas market rules and to push the EU away from spot-pricing toward long-term contracts favoured by Russia’s Gazprom. Seeking rapid certification of the Nord Stream 2 pipeline to boost German gas deliveries could be part of the strategy.

Why is Nord Stream 2 such a sensitive issue? Part of the challenge is Ukraine’s concern that the new pipeline will tighten Moscow’s grip over the region’s energy supply and further strengthen its influence. During German Chancellor Angela Merkel’s final visit in October to Kyiv before leaving office, she acknowledged Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky’s concerns over the project. As well as unease about the regional energy supply balance, Mr Zelensky is worried about what happens in three years when the contract to deliver Russian gas through Ukrainian pipelines terminates. The loss of billions of dollars in transit fees would hit Ukraine’s economy hard.

Mrs Merkel, who also held talks with the Russian President, promised to provide more than a billion dollars to help expand Ukraine’s renewable energy sector but also said sanctions could be used against Moscow under an agreement between Germany and the US, if gas was “used as a weapon”.

Healthy Scepticism or Not?

These complex factors may also be overprinted by a degree of paranoia around Russia’s intentions should Europe become too reliant on Russian gas. But is this concern premature? According to the statistics that Gazprom has been publishing over the last few quarters, it seems that they are close to their full productive capacity, and it could therefore be very challenging for them to simultaneously meet domestic demand, replenish their own storage facilities, and meet their export commitments to Europe in the short term.

The concerns around Ukrainian gas transit fee losses are not clear cut. In 2018 Gazprom delivered more than 200 Bcm of gas to Europe (including non-EU countries), of which 87 Bcm transited through Ukraine. With forecast sales of over 200 Bcm to Europe beyond 2019, Gazprom sees a continuing role for Ukraine and looking further ahead, the steep decline in European gas production will leave a supply gap to be filled by increased imports of approximately 120 Bcm per year. Nord Stream 2 will be able to transport 55 Bcm per year, so even at full capacity it could not meet all the extra demand, theoretically retaining a need for Ukrainian pipeline capacity. This does not mean that Russia couldn’t put pressure on Ukraine by restricting gas supplies through their territory, but it would be a lose-lose scenario. There has also been concern that Germany undermines EU energy solidarity by supporting Nord Stream 2, but because of the increasingly integrated and interconnected nature of the EU internal gas market, this is a project that could benefit all of Europe. The offshore pipeline will be connected to the EU internal market at the German landfall, from which gas can flow anywhere it is needed in Europe, at prices set by the market.

The reality is that with EU gas production projected to decline by half in the face of continuing demand for gas, Europe’s future energy security will depend on reliable imports and this supply gap will need to be closed by Russian gas and LNG in competition with each other – or some other supply. The EU has created a functioning internal energy market in which natural gas competes with other energy sources – and gas-exporting countries compete to supply the market.

A Short-term Problem?

The EU may be hoping the current gas crisis is a short-term phenomenon, but it would be unwise to assume so. A very mild winter might allow Northern European countries to limp through until gas demand slackens in the spring and gas stores replenish, but longer term, secure gas supplies will be needed. If less reliance on Russian gas is considered a good thing, then perhaps working to improve Europe’s indigenous gas supply situation might be sensible – though environmental, social and corporate governance barriers seem to be an impediment to progress here. At least until the lights go out.

Thumbnail image source: Shutterstock