The last couple of decades has seen tremendous economic growth in the countries that make up the Association of South East Asian Nations (ASEAN) – Brunei Darussalam, Cambodia, Indonesia, Lao People’s Democratic Republic, Malaysia, Myanmar, Philippines, Singapore, Thailand and Vietnam. This has brought enormous benefits and opportunities to the region, together with many challenges. Demand for energy, particularly for access to electricity, continues to rise and is projected to grow by an average of 4.7% per year until 2035 across the region. Incomes have increased substantially and fewer people are living in poverty, but with growth has come higher levels of air pollution and increases in CO₂ and other emissions.

Coal and Gas Dominate Electricity

Since 2000, overall energy demand in the region has risen by over 80% and most of it has been satisfied by fossil fuels, particularly coal. In fact, according to the International Energy Agency (IEA), South East Asia is one of a few regions in the world where the share of coal in the power mix increased through the last decade. Based on present policies, it is projected to continue rising, possibly not peaking until 2027, according to Wood Mackenzie. Part of the attraction of coal is that it is mostly supplied from within the region, thus reducing its cost.

Energy demand is driven by rapid growth in electricity consumption, particularly for cooling, which is set to continue, since less than 20% of households in the region have air conditioning at present. Coal is predominantly used in electricity generation, with new plants still being built. In 2018 it accounted for about 40% of electrification in South East Asia and some estimates suggest it may still be contributing as much as 36% in 2040. Change is in the air, however; the Philippines, for example, recently announced a moratorium on any increases in coal-fired power generation, and in the first-half of 2019 approvals for new coal-fired projects were exceeded by additions of solar capacity for the first time.

Gas accounted for 35% of electricity generation in 2018 and is projected to increase its share slightly in coming years. However, local gas production is not anticipated to be able to cover the projected increase in demand and the region may change from being self-sufficient in gas to becoming a net importer by the end of this decade, unless major new fields are discovered.

Scope for Renewables

South East Asia has considerable potential for renewable energy but in 2018 these only accounted for 15% of the region’s total energy demand (IEA). ASEAN has set an ambitious target of securing 23% of its primary energy from renewable sources by 2025.

About 22% of the region’s electricity comes from hydropower, output of which has quadrupled since 2000. Vietnam is the main producer, but there is also potential in other countries such as Cambodia, Indonesia and Thailand. However, the overall financial cost is similar to that of coal and there are environmental issues associated with the dams involved, such as damage to communities and soil health.

As of 2018, other renewable energy sources accounted for less than 10% of South East Asia’s electricity supply, but this is set to increase rapidly, with Wood Mackenzie projecting that solar and wind power plants will contribute 35% of the region’s power mix by 2040. Vietnam, for example, had a tenfold expansion in installed solar capacity in 2019, partly driven by a generous 20-year feed-in contract. The region is an important producer of components such as photovoltaic (PV) cells; Malaysia is already the world’s third-largest producer of them, while Thailand is increasing PV output for both home and global markets. This will assist in energy security for the region, alleviating the increasing dependency on imported hydrocarbons.

Another source ripe for development is geothermal energy. The Philippines is the world’s second-largest producer of geothermal electricity after the US, and Indonesia is also producing an increasing volume, with plenty of scope for expansion. The use of bioenergy (excluding the traditional use of biomass for cooking) in heating and transport has also increased rapidly in recent years, accounting for about 15% of power generation at the moment. Thailand is the leader in this sector both for energy production and in the use of gasohol, a blended fuel of gasoline and bioethanol derived from crops such as molasses, cassava and sugarcane juice.

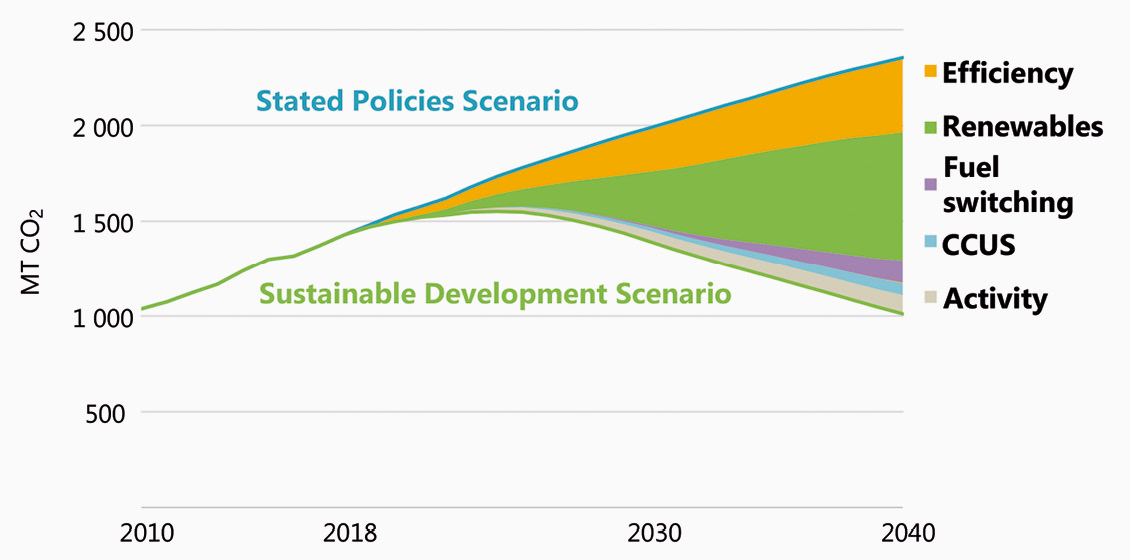

In late 2020 the ASEAN nations launched the Energy Transition Partnership, which aims to support sustainable energy transition in South East Asia in line with the Paris Agreement, with an initial focus on countries like Indonesia, Vietnam and the Philippines, which have significant coal consumption. There is plenty of scope for a variety of energy sources in ASEAN countries and the use of sustainable energy sources both domestically and industrially are increasing fast. However, to deliver on the Paris Agreement level of emissions, coal-fired power plants need to be switching to gas, while the uptake of renewables will need to grow substantially; the IEA, for example, estimates that the share of renewables in power generation will need to reach about 70% by 2040 to achieve this.

Regional Policies Needed

Regional power system integration could hugely help the uptake of renewables in South East Asia, allowing access to a flexible variety of energy sources to help reduce the innate variability of wind and solar energy. Such integration will need high levels of investment from both government and the private sector, as well as commitment through consistent government policies, including the phasing out of fossil fuel subsidies, increased use of carbon capture and encouraging ways to improve energy efficiency.

With the help of renewable energy sources, universal access to electricity across South East Asia is within reach, which would be a major achievement for this rapidly growing region.