“I spent days, if not weeks, trawling through high-resolution photos,” a geoscientist from an oil and gas company recently told me. Why did he do that? He carried out this task because of a new field development, which demanded a new gas pipeline to be built. Before that work can begin, it is common practice to have an ROV capture the trajectory in high-resolution photos and videos, resulting in a massive amount of data to be analysed.

The geoscientist described going through the photos one by one, describing what he saw and trying to find any obstacles or gullies that could compromise the integrity of the pipeline. It all sounded like a monumental task, especially because of the amount of data available for analysis.

Mapping life

Then, totally independent of this initial story, I saw a post on LI the other day from Dani Schmid. He is the founder of Norway-based Bergwerk, a company that specialises in developing tools that help minimise the impact of natural resource extraction.

One of the projects that Bergwerk has recently been involved with is the use of seabed imagery to automatically detect and classify marine benthic life. The main driver for the project is Norway’s ambition – or at least for some people in Norway – to start a seabed minerals industry. One of the key aspects of this future industry is the emphasis on environmental monitoring; a detailed environmental baseline assessment will always be required before any activity can take place.

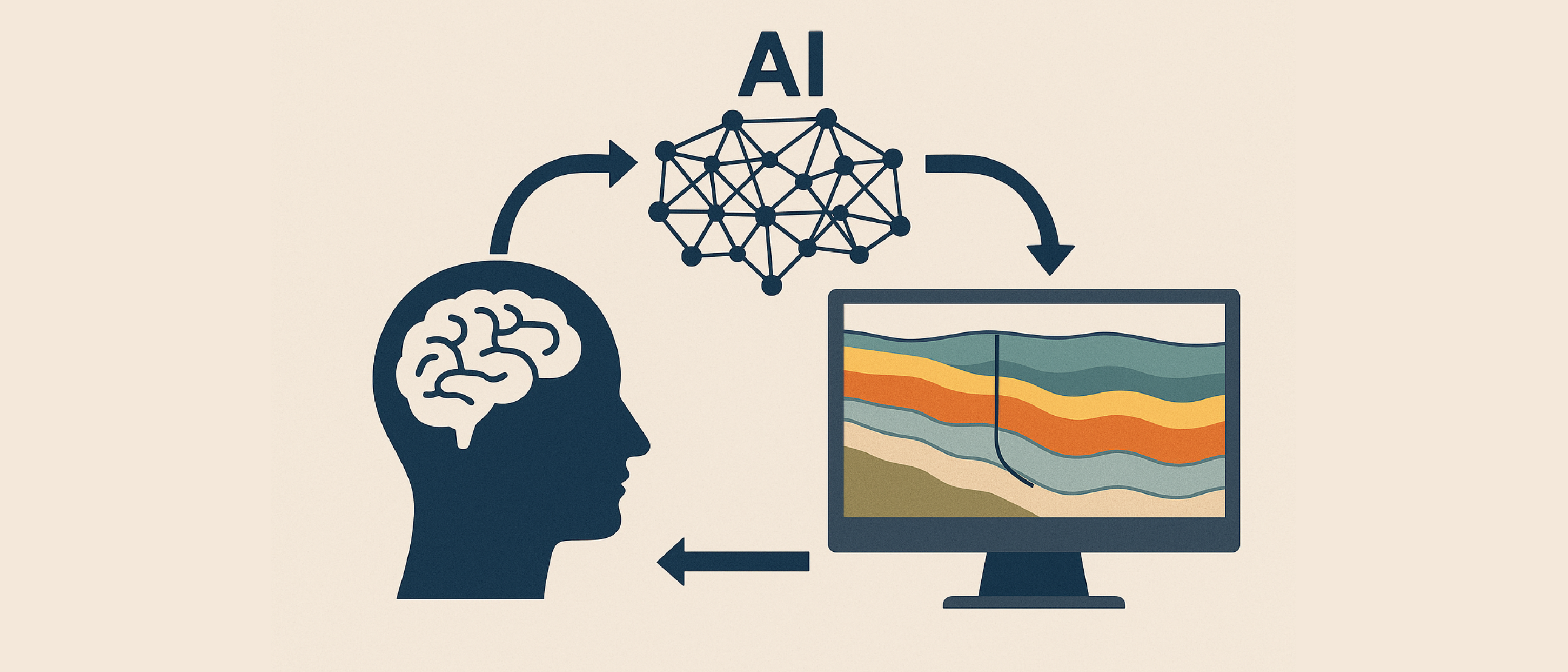

In collaboration with Aker BP, an oil and gas company with a strong presence on the Norwegian Continental Shelf and a commitment to gathering and sharing seabed data, Bergwerk developed an AI-powered methodology to detect marine organisms characteristic of the North Atlantic region. The results were published earlier this year in Frontiers in Marine Science.

The team used the so-called DeepSee dataset, which is a comprehensive collection of annotated images from the Arctic Mid- Ocean Ridge, the Norwegian Sea, and the Greenland Sea. Designed to support the development of ML models capable of detecting and classifying benthic organisms, the DeepSee object detection model was trained on this dataset.

Following rigorous testing, the workflow is now capable of processing vast amounts of footage quickly with high precision and accuracy, identifying most species that occur in the area. As such, the model provides a valuable addition to the traditional workflow of manual annotation by significantly reducing the load on marine biologists.

In the paper, the authors already mention the application of their workflow to pipeline laying projects. And given the technology available, it should also be possible to expand the model’s capability and include the identification of drop stones that can form unwanted obstacles for a pipeline that prefers to go straight ahead. It could have saved the geoscientist I spoke to quite some time.