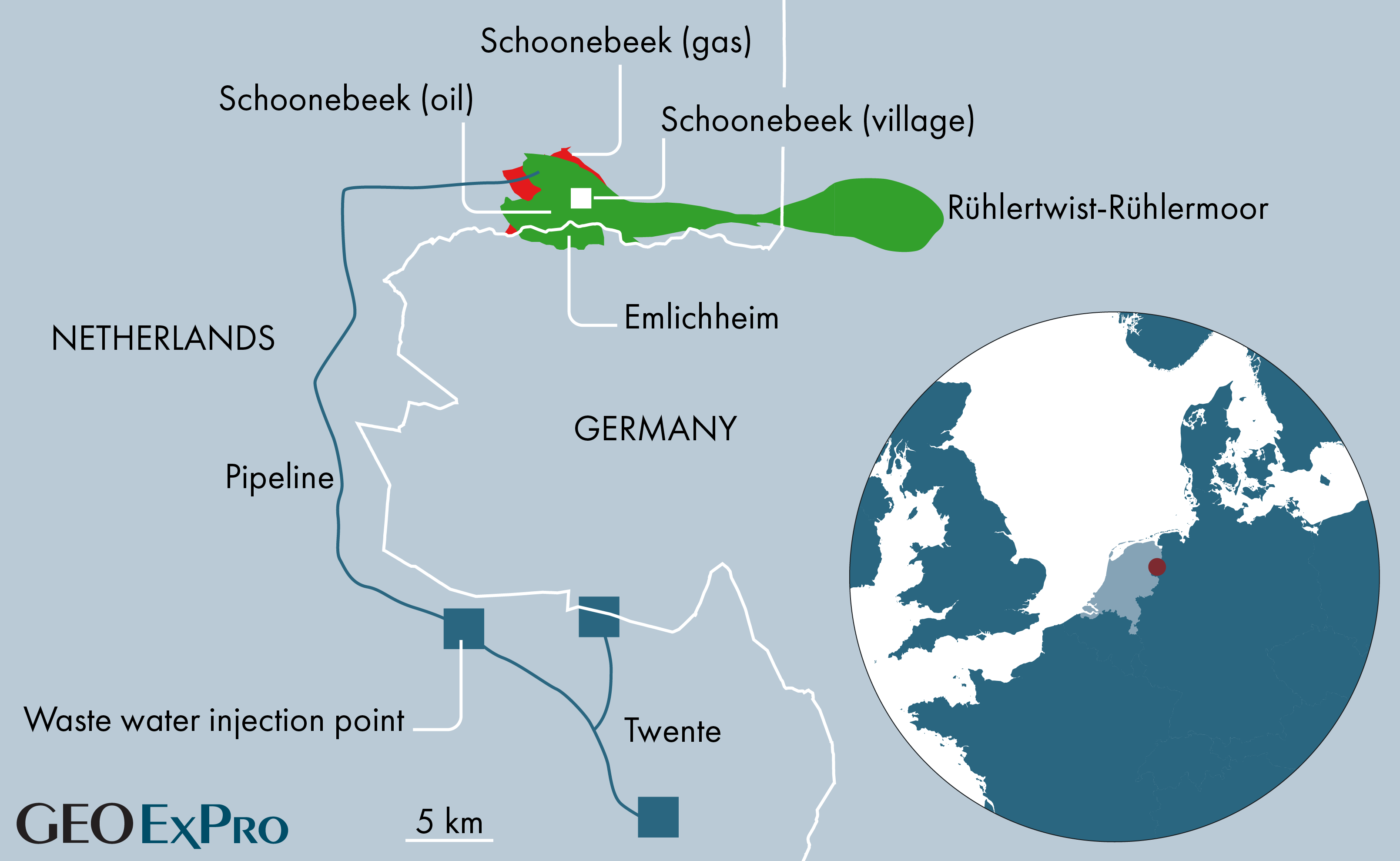

When looking at a map of the Schoonebeek oil field and its equivalent in Germany (see below), one would almost think that the Germans and the Dutch agreed on the national border after the discovery of this field to ensure that both countries would have a slice of this attractive pie. That’s not true. When Schoonebeek was discovered in 1943, the boundary between the countries had already been in place for a long time.

Fast forward to today, the field has been independently developed both from the German and Dutch side of the border, using different production strategies. Whilst nodding donkeys have characterised the operational landscape in the German part of the field ever since production started, NAM abandoned this way of production in 1996, only to re-start production from Schoonebeek in 2011 using a system of long horizontal producers and steam injection at the same time.

Stealing oil

The reason why the Schoonebeek field could be developed by two different companies without the risk of interference is the fact that the oil is quite heavy – 25° API. Also, because of the low temperature at a depth of around 700 m where the 20-30 m thick reservoir is situated, any well drilled into the reservoir will not “see” far into the formation and the risk of seizing the neighbour’s oil is therefore small. The NAM expected to produce another 120 MMboe from Schoonebeek when production started again in 2011.

As Schoonebeek oil comes with a high water-cut of around 90% or higher, the separated water was re-injected in three abandoned gas fields in the Twente area south of Schoonebeek, using an existing 70 km long pipeline to transport the fluids. However, this led to microbially-induced corrosion and the risk of leakage. This was subsequently remediated through the fitting of flexible pipes into the existing pipelines, ensuring minimal disruption and allowing quick resumption of operations.

However, a downhole rupture in the outer casing wall of one of the Twente injection wells was also found. Even though it did not lead to the leakage of fluids, NAM was accused of not picking this up in a timely manner. This helped trigger an outcry of public anger in the Twente area, which ultimately led NAM to stop water injection in August 2021. This also meant that the production of oil from the Dutch part of this major oil field came to a stop.

With the Twente area looking increasingly difficult when it comes to re-starting production, NAM is currently looking at re-injecting produced water much closer to the field. The company now aims to drill four new injection wells into Zechstein carbonates below the Schoonebeek Cretaceous oil reservoir. Gas was previously produced from these Zechstein carbonates (Schoonebeek gas field on map), so the pressure has depleted significantly, allowing for the injection of water. These plans are currently being evaluated by the responsible authorities.

Groningen versus Schoonebeek

Maybe it is a better idea to inject the water more locally than it was done before. The village of Schoonebeek hosts a community has overall been supportive of continued oil production in the area. In contrast to Groningen, where most people cannot wait to see NAM leave the place, oil production in Schoonebeek was never challenged to the same extent due to a level of trust between parties and the involvement of local people in the oil-production job market.

But, it must be said that even in a place like Schoonebeek, NAM cannot just press on with drilling the new injection wells. People in the village have also expressed their concerns and have come together in a group that is critical towards its plans. At the same time, there is also a group that emphasises the benefits continued oil production brings, coupled with a level of trust that operations will be carried out succinctly.

As is so often the case with subsurface activities, the discussion centres around risks. What is the chance that leakage will occur, and what is the probability of induced seismicity? It is no surprise NAM cannot guarantee nothing will happen, but as Manuel Sintubin from Leuven University in Belgium says in an interview, when he addresses the risk of induced seismicity being minimal as long as the injection pressure does not exceed the fracture pressure: “This should give people some comfort.”

Ultimately, it will be down to the Dutch authorities to approve NAM’s plans, but it is clear that even in a village where the oil industry has been a strong partner in the local community, the licence to operate is not a given anymore.