The trek begins near the village of Sembalun, which straddles the northeast edge of the Rinjani National Park. Starting at 600m elevation or so, walking through the lowlands is an oddly Alpine experience: cowbells, flurrying grassland and even ‘Javanese edelweiss’ (Anaphalis javanica) further up.

This comparison can only stretch so far, and is broken by the sighting of macaques. Long-tailed grey macaques (kera) are ubiquitous in Lombok and further afield, and the reader must wait to hear about anything more exotic. The track traces an abandoned road, once used to supply an outpost, and is easy to follow as far as it goes.

Nonetheless, even experienced hikers are cajoled into hiring a guide, as it is an official requirement. Initially I resented this imposition: why would I pay to be led up a well-trodden path? Through time and enjoyment of the walk, my stance mellowed, and I accepted that the system kept the park clean and funded it. I felt a little sorry for my guide, who was fasting for Ramadan and unsurprisingly found the climb difficult! The porters work even harder, yoked (literally) with food for three days, crockery, tents, latrines and, for the spendthrifts, deckchairs.

Towards the crater rim, the slope steepens and the old road runs out. The landscape is at its most eerie: drifting in and out of the mist, one passes through an ever-changing flora. Lonely, warped trees are succeeded by a sparse forest of slender white cemaras (resembling conifers). There is a thickening undergrowth of ferns, bamboo, orchids and asters. The path dips in and out of deep gullies and crosses thick andesite flows.

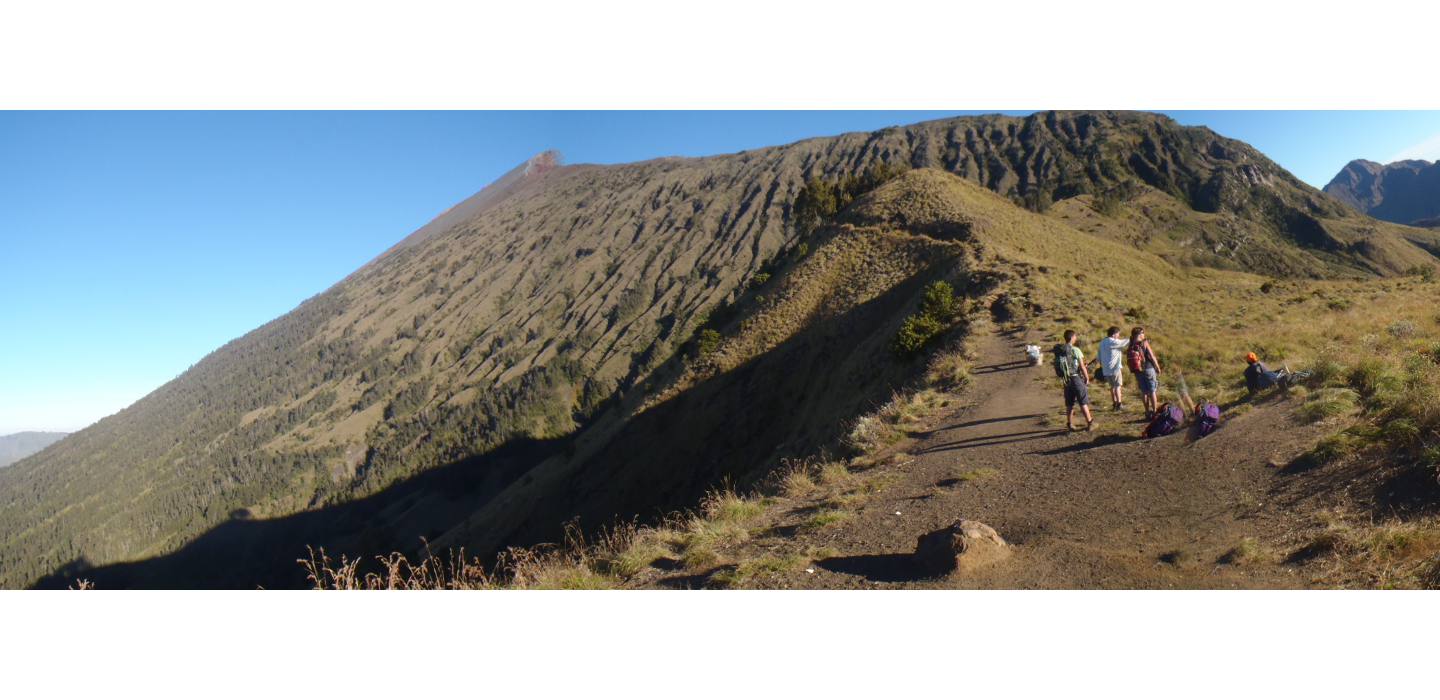

Ascent to the crater rim. (Source: H. Matchette-Downes)

Ascent to the crater rim. (Source: H. Matchette-Downes)

Spectacular Views

Abruptly, I was on the crest, and could see into the caldera for the first time, and my eyes scanned along its toothy edge, seeing the far side four miles away. Looking down, there sat Anak Luat, or Child of the Sea, a sacred lake so named for its azure colour. This blue is probably due to geothermally introduced sulphur particles. Presiding over the lake is the small, perfect cinder cone of Gunung Baru, New Mountain, which has risen from the floor of the caldera.

Camp. Day 1. (Source: H. Matchette-Downes)The sun was setting but we had reached the first camp. It had been a seven-hour walk or so, reaching around 2,700m above sea level. After examining the stars, very clear in this thin air, I was able to sleep long before my usual bedtime.

Camp. Day 1. (Source: H. Matchette-Downes)The sun was setting but we had reached the first camp. It had been a seven-hour walk or so, reaching around 2,700m above sea level. After examining the stars, very clear in this thin air, I was able to sleep long before my usual bedtime.

This was just as well, as we woke up at 2.30 in the morning so we could reach the top in the dark, see the sunrise, and avoid fierce high-altitude UV. The summit of Rinjani is at 3,726m, making it the second-highest volcano in Indonesia, behind Mount Kerinci in Sumatra.

I would not describe it as a noble peak, as it is the ruins of a taller volcano thought to have exceeded 5,000m: imagine Mount Fuji, but bigger! A recent paper convincingly argues that the crater-forming eruption was ‘the great A.D. 1257 mystery eruption’, and one of the greatest of the Holocene. Evidence is drawn from local stratigraphy, geochemical matches with both polar ice caps, and carbon dating of charred trees. There is even a preserved manuscript, Babad Lombok, written in Old Javanese on palm leaves, which records a catastrophic eruption of Rinjani. Historical chronicles worldwide recall the cold, rainy year of 1258, which led to floods and famine. The eruption could have contributed to the ‘Little Ice Age’, a cold snap defined variously within the 14th–19th century range.

Descent into caldera. (Source: H. Matchette-Downes)The walk was strenuous, especially near the peak. It followed the narrow rim clockwise, over scoria and ash, with the classic volcano shape of 35° angle-of-repose slopes to one side, and a sheer cliff to the other. With a fitting sense of drama, the last stretch was the steepest, and it was a case of three steps forward and two slipping back.

Descent into caldera. (Source: H. Matchette-Downes)The walk was strenuous, especially near the peak. It followed the narrow rim clockwise, over scoria and ash, with the classic volcano shape of 35° angle-of-repose slopes to one side, and a sheer cliff to the other. With a fitting sense of drama, the last stretch was the steepest, and it was a case of three steps forward and two slipping back.

From the top, one can see all of Lombok and far beyond. Before the sun arrives, the capital Mataram glows and the nightclubs of the Gili Isles twinkle. As it rises, the adjacent links in the volcanic chain are clear: Tambora (on Sumbawa) to the east and Agung (on Bali) to the west. In fact, the Sunda volcanic arc stretches much further west, to the northern tip of Sumatra. One can easily see the arc on a map, cradling South East Asia, and its volcanoes are often in the news. This February, Mount Sinabung (Sumatra) and Mount Kelud (Java) both erupted violently.

Rinjani sits between two tectonic regimes. The Sunda arc is a clear example of a subduction zone, as the Australian plate moves northwards beneath the Eurasian plate. Tracing east along the arc, one sees that the series of volcanoes runs out soon after Lombok. Until about 3 Ma ago, the subduction continued further east, but at that time, the Australian continental shelf reached the subduction zone. This had two consequences. Firstly, the volcanic arc was thrust over the Australian crust, forming a substantial part of modern Timor. Secondly, the subduction was choked, ceasing volcanic activity. Above Timor, north-facing thrusts (Wetar and Flores) indicate an incipient reversal of subduction direction.

Looking down into the caldera from the summit. (Source: H. Matchette-Downes)

Looking down into the caldera from the summit. (Source: H. Matchette-Downes)

Crater Lake

After reaching the summit, the next leg is back to camp and then down into the crater to take a closer look at the lake. It is a great relief to be travelling (in some cases hurtling!) downhill. The inner walls of the crater are very steep, and so the path must exploit a valley through which the lake runs into the Bali Sea. The point of outflow is also a source of sulphurous hot springs which provide a welcome opportunity to remove the dust and wash one’s feet.

The lake itself is not warm, but good for swimming. It covers around four square miles (10.4 km2), in a rough crescent shape, and is said by the Park authorities to be over 200m deep. Fish, probably introduced through Hindu ceremonies, are common. The lake is also holy to Lombok’s majority faith, Islam. From the west side of the lake there is a view of Gunung Baru’s main vent, which last erupted in 2010; like most stratovolcanoes Rinjani is fairly active.

We climbed out of the crater on its western edge, finishing as the sun set and completing 16 hours of walking and covering 38 km. Fortunately, the final half-day is all downhill towards the village of Senaru. The western flank of the volcano has more pristine rainforest, where I saw acrobatic Ebony Leaf monkeys (lutung) and heard their toad-like calls. Lombok is just east of the Wallace line and has an unusual mix of fauna. There were signs of other animals, such as wild pigs, but I was sad not to catch a glimpse of the deer, wildcats, owls, birds and porcupines known to live here.

After the trek, I asked my guide what ‘Rinjani’ meant, or where the word came from. He thought it just meant ‘big’. No other source to my knowledge confirms or refutes this. I don’t think it is a very appreciative epithet: there are plenty of big mountains, but none of them is anything like Rinjani.

About the author:

Harry Matchette-Downes studies physics and geology at the University of Cambridge.