Recently published maps of the Sangomar field offshore Senegal depict the southern boundary of the accumulation exactly lining up with the maritime boundary between Senegal and The Gambia, suggesting that there is no extension into The Gambia. Such a coincidence should raise eyebrows with any geologist or even with those without much knowledge of subsurface geology. It just looks odd to see an oilfield boundary lining up with what is essentially a human-derived line. That’s why I published a story last year about the possibility that a small part of the Sangomar field does extend into The Gambia.

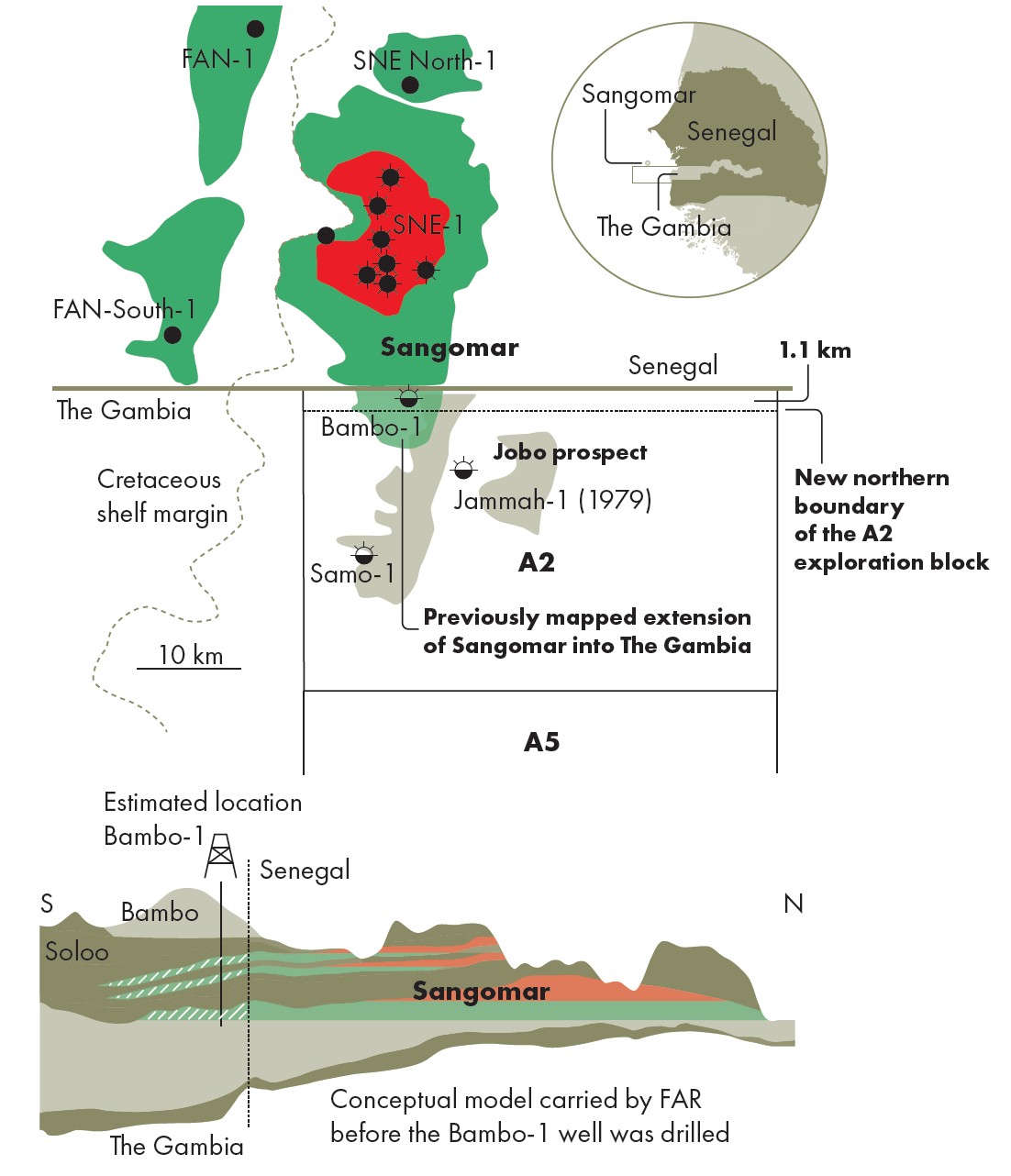

In fact, during the initial exploration and appraisal of Sangomar, which took place between 2014 and 2020, companies involved in exploring the area were all of the opinion that Sangomar did indeed extend into The Gambia. The boundary took a much more natural shape at the time. The implications for a country without commercial hydrocarbon production were substantial: There was considerable optimism that The Gambia might soon realise its first oil revenues. And with Australia-based FAR, through its subsidiary FAR Gambia, drilling two wells – Samo-1 (2018) and Bambo-1 (2021) – in Gambian waters, there was real excitement that things would materialise.

However, as I described in the previous article, after the drilling and completion of these two wells, both of which were targeting reservoirs thought to be within the possible extension of the Sangomar field, the mood turned around quickly. FAR reported that both wells had been unsuccessful and soon after relinquished their licence after failing to attract new joint venture partners.

In the article, I argued that even though the Bambo well was reported dry, this does not allow the conclusion that there is no Sangomar oil to be found in The Gambia at all. Here, I’d like to add some observations further supporting that view, in addition to looking back at a FAR presentation that is still accessible and that sheds an interesting perspective on the matter. Finally, I will draw attention to a recent development – the shift of the northern boundary of the A2 exploration block in which the two exploration wells were drilled.

The problem with “poor reservoir quality”

The main reason for FAR to discount the Bambo-1 well results was the observation that the quality of the Sangomar-equivalent section encountered in the well was too poor to be regarded as a reservoir. This may be true, but that doesn’t mean it justifies the conclusion that all strata representing the extension of Sangomar into The Gambia have the same poor reservoir properties.

There are plenty of examples of oil exploration wells that “undiscovered” a field before the next well hit the jackpot. An instructive example is the Forties field in the UK North Sea that was first drilled by a well that accidentally penetrated a levee system of the deep-water turbidites that make up the field’s reservoirs. It was only with the second well that better quality reservoirs were found. The same might have happened with Bambo; there must be a sedimentological explanation behind the well result, and therefore it would still be very particular if that facies boundary would line up exactly with the international boundary.

They were all convinced

Prior to drilling the Bambo and Samo wells, there was little doubt that Sangomar extended into The Gambia. Peter Nicholls, FAR’s chief geologist, articulated this in a video that can still be watched online. He says: “… Woodside and the other joint venture partners in SNE all see that the Sangomar field does extend into The Gambia, so that’s not a contentious issue. It’s the way it is seen and mapped as just extending into our block (A2). So, we are now going through an evaluation to see what volume we now have in our block.”

It is of particular interest to hear Peter saying that all joint venture partners had the same vision about Sangomar extending further south. This only puts more question marks to the maps that are now circulating. Woodside Energy, having operated in the region throughout, is uniquely positioned to influence interpretations of the field’s extent. The subsequent shift in the mapped boundary of Sangomar, now terminating at the Senegal – Gambia line, appears to be a post-hoc redefinition.Was this shift geologically justified? Or was it a convenient administrative closure that, intentionally or not, excluded The Gambia from further discussion?

Shifting boundaries

Then there is the more recent issue of redrawing offshore block boundaries by The Gambia’s government in 2023. While two of the A2 block’s corner coordinates remained unchanged, the northern boundary was shifted more than a kilometre to the south, resulting in the Bambo well falling outside the new block limits.

This raises several questions. What justified this redefinition, which resulted in the Bambo well being excluded from the block? The result is a 1.1 km strip of marine territory between the A2 block and the national border that coincidentally corresponds to where any transboundary Sangomar extension would logically lie.

Is this shift unrelated to administrative housekeeping? Or does it hint at an intentional move to delink the Bambo data from future licensing rounds and potential resource claims?

The case remains open

In conclusion, despite recent maps suggesting Sangomar does not extend into The Gambia, well results, geological observations, previous work done by exploration geologists in the area, and recent block boundary changes all keep the question very much alive: Is it really true that there is no Sangomar reservoir extension in Gambian waters?

Until there is comprehensive disclosure of the reservoir data, and an assessment of reservoir quality based on seismic inversion results, the possibility of a Sangomar extension into Gambian waters must remain an open and serious question.