he rapid development of unconventional resource plays throughout numerous geographical areas of the United States have one thing in common: they all are associated with the use of significant amounts of fresh water , although recycling is increasing. Unconventional natural gas resource plays either need water for development, as is the case for tight gas sands, shale gas and tight oil, or require water to be withdrawn to facilitate the development, as is the case for coal-bed methane.

Water Use Issues

The Barnett Shale Play in north central Texas has been undergoing development for over ten years. Over 19,000 wells have been drilled and this trend is expected to continue for decades. Operators in the Marcellus Shale Play (New York and Pennsylvania) are being confronted with severe restrictions on available water for hydraulic fracturing and the lack of facilities to treat or dispose of contaminated flow-back water.

The sources for the New York City reservoir system are three large watersheds that are underlain by the Marcellus Shale. New York has banned hydraulic fracturing while they continue to study this commonly used and historically safe method for stimulating shale formations. In addition, many of the communities in the path of this development have never experienced natural gas drilling and development activities. Residents are concerned that their water resources will be negatively impacted by contamination and excessive withdrawal of groundwater or excessive use of surface water. Their lack of industry knowledge and the overriding presence of many new operators are presenting significant challenges to natural gas development.

By comparison, tight gas sands in the North Louisiana-East Texas Upper Gulf Coast Basin have been exploited with vertical wells and single stage hydraulic fracturing wells for decades. The Haynesville Shale Play of northern Louisiana and eastern Texas developed very rapidly from 2008 through 2012; over 2,500 wells have been drilled in this play with over 2,200 producing in Louisiana alone. Now accounting for over 60% of Louisiana’s gas production and with very high initial production rates up to 30 Mcfgpd, the Haynesville Shale is one of the richest gas plays to date.

A Wake-up Call

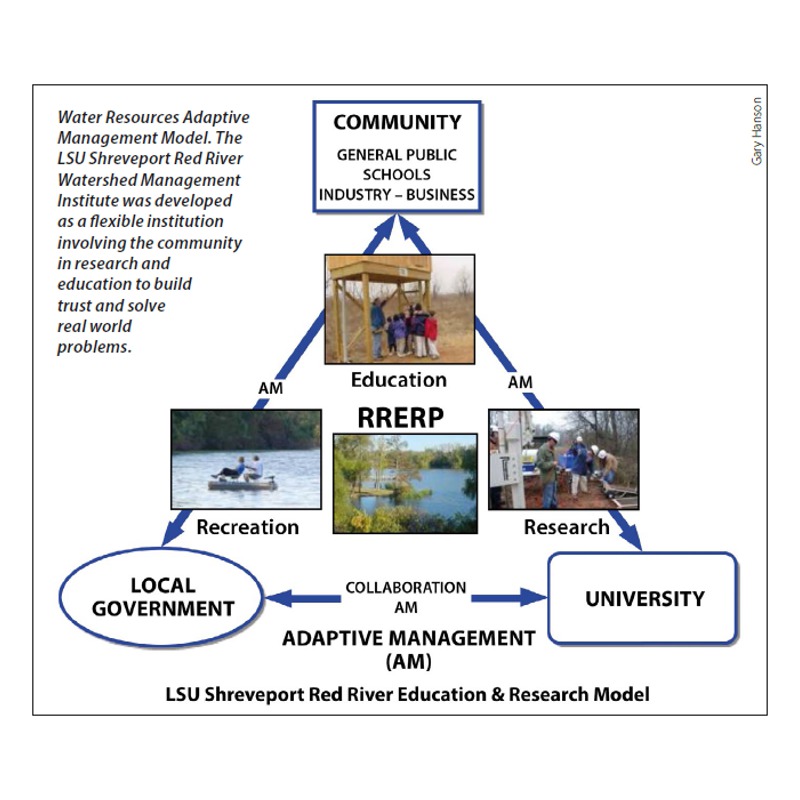

Early in the Haynesville Shale development, significant water use issues surfaced, and the gas industry encountered a public that was aware of existing groundwater problems associated with gas production. Prior to the start of the Haynesville Shale development, the Red River Watershed Management Institute at Louisiana State University Shreveport and Caddo Parish jointly developed a groundwater monitoring well programme. In addition, the Water Resources Committee of Northwest Louisiana was established to address water issues and would later spawn a water energy working group at the university.

Early in the Haynesville Shale development, significant water use issues surfaced, and the gas industry encountered a public that was aware of existing groundwater problems associated with gas production. Prior to the start of the Haynesville Shale development, the Red River Watershed Management Institute at Louisiana State University Shreveport and Caddo Parish jointly developed a groundwater monitoring well programme. In addition, the Water Resources Committee of Northwest Louisiana was established to address water issues and would later spawn a water energy working group at the university.

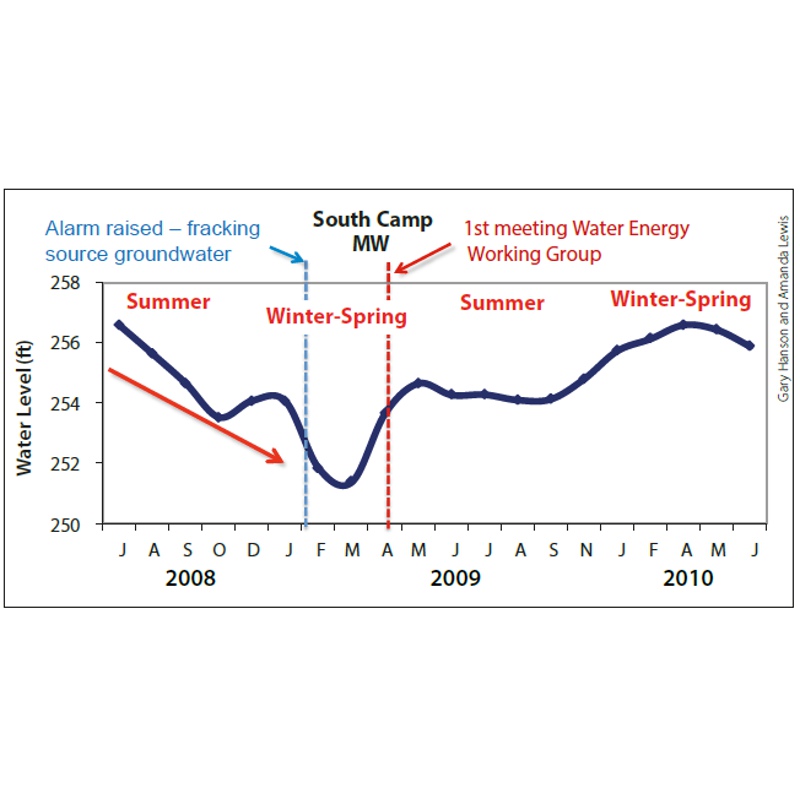

With rapid shale gas development came large numbers of groundwater wells to provide water for drilling and fracking operations. Early data from the groundwater monitoring project showed that the local Carrizo-Wilcox Aquifer was not capable of producing sufficient water for all the users involved. For all of this development to continue, changes in water use had to be made.

Data collected by the Red River Watershed Management Institute from the area’s main aquifer showed a sharp drop in water levels near Haynesville Shale development. Gas companies recognised the problem and quickly adjusted to using more abundant surface water for drilling and fracking operations.This new data was important to operators in the area in that they could see the aquifer was being negatively impacted near their gas development and started looking for alternative sources of water. The working group quickly concluded that they needed access to non-potable and underutilised surface waters to continue development operations. The Red River, its underlying Red River alluvial aquifer, and treated wastewater from a paper mill were the obvious choices. The group convened numerous meetings to iron out the many issues facing them.

Data collected by the Red River Watershed Management Institute from the area’s main aquifer showed a sharp drop in water levels near Haynesville Shale development. Gas companies recognised the problem and quickly adjusted to using more abundant surface water for drilling and fracking operations.This new data was important to operators in the area in that they could see the aquifer was being negatively impacted near their gas development and started looking for alternative sources of water. The working group quickly concluded that they needed access to non-potable and underutilised surface waters to continue development operations. The Red River, its underlying Red River alluvial aquifer, and treated wastewater from a paper mill were the obvious choices. The group convened numerous meetings to iron out the many issues facing them.

Having participants such as groundwater and surface water hydrologists, water resource managers and levee board representatives, in addition to the technical oil and gas disciplines (petroleum geologists and engineers) made this truly trandisciplinary and non-statutory approach enjoyable and fruitful.

Developing a Water-Energy Model

Two critical natural resources, energy and water, are key ingredients for a healthy and secure economy in any country today. These resources are linked closely, as the production of energy requires significant quantities of water to be sustainable and the distribution of large quantities of clean water are dependent on low cost energy.

This is the ‘energy-water nexus’ that is being challenged by a growing number of issues. Add to this food supplies; the challenges at a global level have been there for some time but are now becoming increasingly urgent.

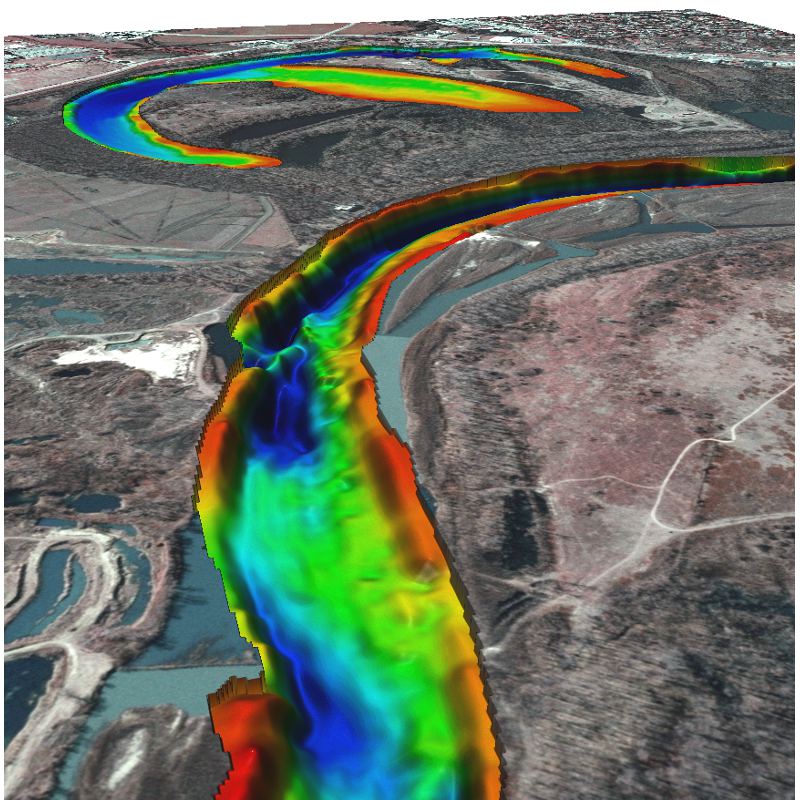

Multibeam sonar images of the Red River area, showing bathymetry of the river (foreground) and Red River Education and Research Park oxbow lake (background). Hot colours represent shallow water and cool colours the deep water. These are some of the shallowest multibeam sonar images ever recorded. (Source: Gary Hanson)With drought conditions and increased demand making water deliverability to the various users in north-west Louisiana problematic, more cooperation between multiple agencies and disciplines becomes a must. As the Red River alluvial aquifer has a shared use between farmers and natural gas operators, the shallow and deep groundwater monitoring wells are providing key data to all the users. Shell Oil is funding research for the Red River Water Management Institute, bringing in Sci-Port-Louisiana’s Science Center, and supporting interns from nearby Bossier Parish Community College to work at the LSU-Shreveport Red River Education and Research Park.

Multibeam sonar images of the Red River area, showing bathymetry of the river (foreground) and Red River Education and Research Park oxbow lake (background). Hot colours represent shallow water and cool colours the deep water. These are some of the shallowest multibeam sonar images ever recorded. (Source: Gary Hanson)With drought conditions and increased demand making water deliverability to the various users in north-west Louisiana problematic, more cooperation between multiple agencies and disciplines becomes a must. As the Red River alluvial aquifer has a shared use between farmers and natural gas operators, the shallow and deep groundwater monitoring wells are providing key data to all the users. Shell Oil is funding research for the Red River Water Management Institute, bringing in Sci-Port-Louisiana’s Science Center, and supporting interns from nearby Bossier Parish Community College to work at the LSU-Shreveport Red River Education and Research Park.

The water-energy-food security nexus will have an effect on all users. Currently, the amount of groundwater and surface water used for the Haynesville Shale Play is only a minor portion of the water budget in most regions. However, during droughts and in arid or semiarid areas, this is not the case. When developing the north Louisiana model for water use and distribution, participants have worked with socio-economic, political, internal industry and agricultural policies to lay out a plan. However, implementing this plan on the ground over time is much harder.

Keeping the water-energy security nexus efforts stable requires continuing efforts from all parties. In the highly competitive oil and gas industry changes in gas prices bring changes in company strategies; for example, when gas prices dropped, operators left the gas-rich Haynesville Shale Play for the liquids-rich plays such as the Eagle Ford in South Texas. Now, with gas prices creeping higher, new operators are moving back to the Haynesville area and are attempting to use groundwater again. It is important that the industry lives up to the agreements that have been worked out over several years and hundreds of hours of effort.

Solving the Problem

Haynesville operators acted quickly with voluntary changes in water usage. Through public outreach and education, this area has not experienced negative backlash associated with the development of tight hydrocarbon resources. Using only an 11 acre (4.5 ha) drill pad, drilling and fracking of a previously drilled well can occur simultaneously – well spacing varies from 45 to 75ft (14 to 23m). Using horizontal drilling techniques minimises landscape impact. With this small pad, multiple wellbores can reach into four sections (2,560 acres, 1,036 ha) in the deep subsurface. (Source: Gary Hanson)There is a need for technical experts and governing bodies to stretch beyond their normal work environment in order to solve these difficult problems. As this relates to the water and energy nexus, the problem to be solved may not, at first, be realised as a common one. At the beginning of the working sessions, no one had the answers to tough real world problems that had to be solved. They started with technical oil and gas people sitting across the table from regulators with practically no knowledge of the petroleum industry but who had the power to determine if wells were going to be drilled or not. Vulnerabilities surfaced, preconceived ideas were neutralised, and internal politics were kept out of discussions. The result was education for all; participants could solve some problems right on the spot while other problems would take more time to solve with additional agencies or experts to be consulted.

Haynesville operators acted quickly with voluntary changes in water usage. Through public outreach and education, this area has not experienced negative backlash associated with the development of tight hydrocarbon resources. Using only an 11 acre (4.5 ha) drill pad, drilling and fracking of a previously drilled well can occur simultaneously – well spacing varies from 45 to 75ft (14 to 23m). Using horizontal drilling techniques minimises landscape impact. With this small pad, multiple wellbores can reach into four sections (2,560 acres, 1,036 ha) in the deep subsurface. (Source: Gary Hanson)There is a need for technical experts and governing bodies to stretch beyond their normal work environment in order to solve these difficult problems. As this relates to the water and energy nexus, the problem to be solved may not, at first, be realised as a common one. At the beginning of the working sessions, no one had the answers to tough real world problems that had to be solved. They started with technical oil and gas people sitting across the table from regulators with practically no knowledge of the petroleum industry but who had the power to determine if wells were going to be drilled or not. Vulnerabilities surfaced, preconceived ideas were neutralised, and internal politics were kept out of discussions. The result was education for all; participants could solve some problems right on the spot while other problems would take more time to solve with additional agencies or experts to be consulted.

The lack of potable water world-wide is becoming a reality. As the population increases and industry grows, more water will certainly have to be made available and all users will have to become more efficient with its use. In the US, shale gas and tight oil plays have become a catalyst to convince the public that water is a topic that can no longer be ignored. This certainly was the case in Louisiana as the arrival of the Haynesville Shale Play made officials take a hard look to find ways to solve the area’s water problems. The actions taken in north Louisiana regarding the energy and water nexus can and should be used as an example for others to follow. Above all, it is absolutely critical that transdisciplinary approaches be taken for the world to maintain secure supplies of energy, water and food.

When it comes to lessons learned, unconventional resource play operators must become familiar with the state or local water issues and usage regulation prior to the start of their operation. It is a very good idea to initiate contact at the outset with local, county/parish, and state agencies to develop a rapport and mutual understanding of proposed operations. Finally, do not underestimate the concerns (perceived or real) of local citizens when it comes to the use and protection of ‘their’ water. Concern about water issues continues to permeate all discussions (whether water related or not) with local government and citizens in the Haynesville Shale Play. Exploration and production management must realise that water issues have to be addressed as a priority early on in any unconventional resource play.

Acknowledgements:

The author would like to acknowledge the following organisations and individuals:

Amanda Lewis, Dillon Soderstrom, Dr. Vincent Marsala and Dr. Paul Sisson, LSU Shreveport; Dr. Woodrow Wilson, Caddo Parish Commission; Ken Guidry, Red River Waterway Commission; Jim Welsh, Louisiana Office of Conservation; Nancy O’Toole, Shell Oil; Dr. John Russin and Dr. Patrick Colyer, LSU AgCenter; Dr. Van Brahana, University of Arkansas; Brandon Calhoun, Chesapeake; EnCana; Ben Warden, Conoco-Phillips; Mark Henkhaus, Apache Corp.; US Corps of Engineers; US Fish & Wildlife Service and USEPA.