Thirty years ago, when I first joined the oil industry, a colleague told me that after telling his bank manager about his new job as a mud logger, the only question was “where are the trees you’re going to be cutting down?”

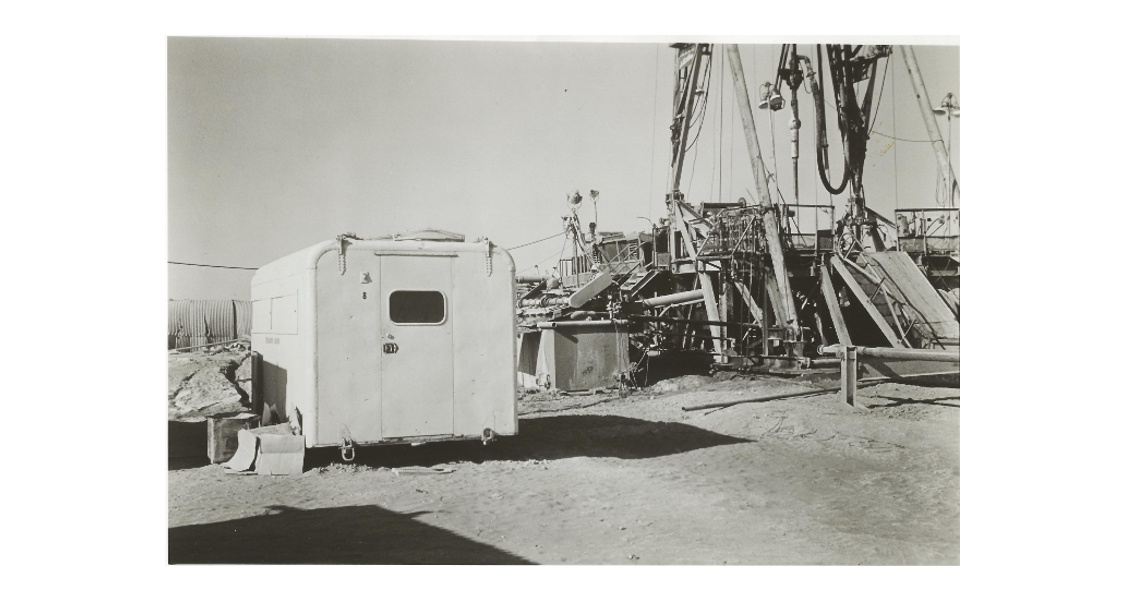

For many geologists working in the oil industry, their introduction to the oil field has been as a mud logger, logging geologist, formation evaluation geologist or surface logging geologist – a multitude of titles for what is essentially the same job. Yet, for a role that is vital for maintaining the safety of the rig, and gives the first indications of what formations are being drilled and of any shows, it is not that well understood, especially by people outside drilling operations.

In truth, I was not that much better informed when I was first interviewed for a mud logging job. I knew it involved looking at and describing rocks on an oil rig, and I had spent the last few years describing rocks, so how hard could it be? A few weeks later, looking through a microscope at what appeared to be an undistinguishable mass of soft grey lumps which I had to describe in the next couple of minutes before dashing off to catch another sample, I began to understand the answer.

Therefore, the aim of this article is to try and explain what mud logging is, why it started and how it developed through to today. Most importantly, I want to explain why I think it is such a valuable introduction to the oil industry which can lead on to a range of careers.

The History of Mud Logging

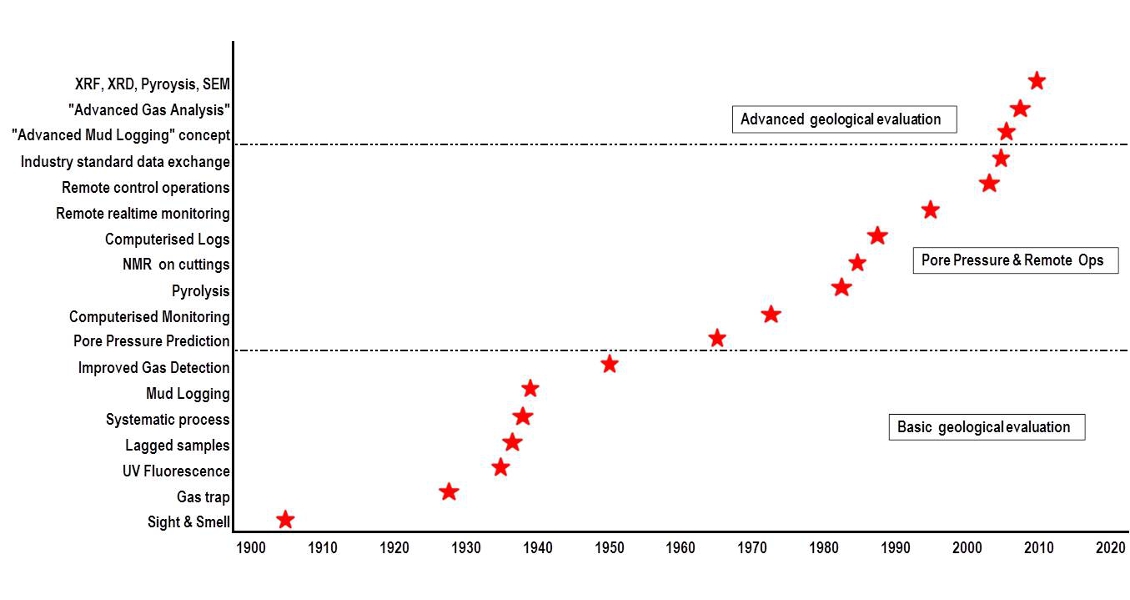

So where did mud logging begin? In the early days of the modern oil industry, wells were drilled where there was evidence of hydrocarbons, such as natural oil seeps, and drilled until oil was found or the money ran out. As the industry developed, geological knowledge was increasingly used to identify potential oilfield locations, but the process of drilling a wildcat well was still essentially blind. The early wellsite geologists had little in the way of evaluation tools and would work by ‘sitting the well’ – literally sitting and observing the drilling mud returning to surface, looking for an iridescent surface sheen indicating oil, or bubbles and foam indicating gas.

In the mid-1920s the first ‘gas trap’, a device attached to the end of the flow line to separate the gas from the mud for analysis, was developed. In the early thirties, ultraviolet light started to be used to detect oil on cuttings by fluorescence. Later that decade it was realized that the returning mud and cuttings could be correlated with depth, by measuring the circulation or lag time of the drilling fluid. In 1940, J. T. Hayward presented a paper entitled ‘Continuous Logging at Rotary-Drilling Wells’, which describes a commercial mud logging unit, still recognizable now.

Today the job of the mud logger has become much more comprehensive and demanding. It is still based around formation evaluation and gas monitoring, but now also includes operations and fluids monitoring.

Formation Evaluation

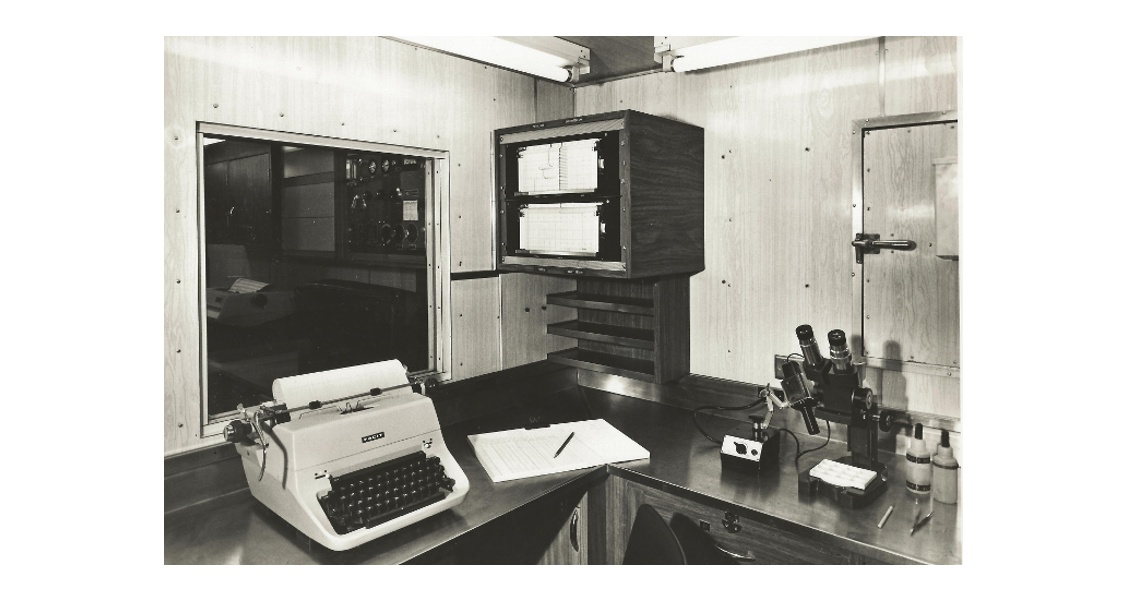

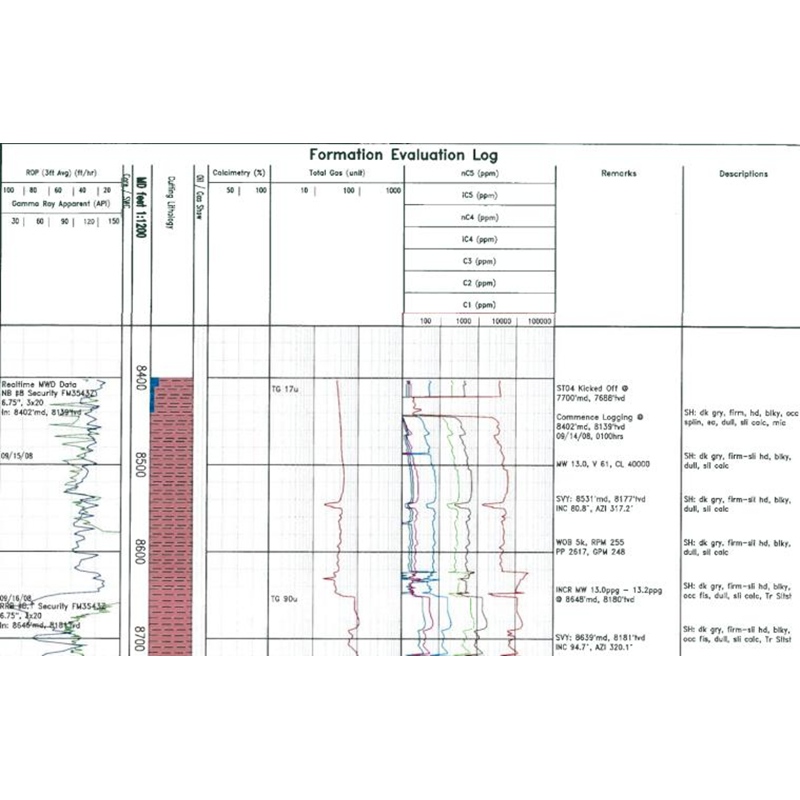

An example of a mud log. (Source: Baker Hughes)Geology remains the foundation of all mud logging services. The mud loggers are the first and in some cases the only people who actually look at the rocks being drilled. Until recently, rigsite evaluation of cuttings had not changed appreciably from the 1940s.

An example of a mud log. (Source: Baker Hughes)Geology remains the foundation of all mud logging services. The mud loggers are the first and in some cases the only people who actually look at the rocks being drilled. Until recently, rigsite evaluation of cuttings had not changed appreciably from the 1940s.

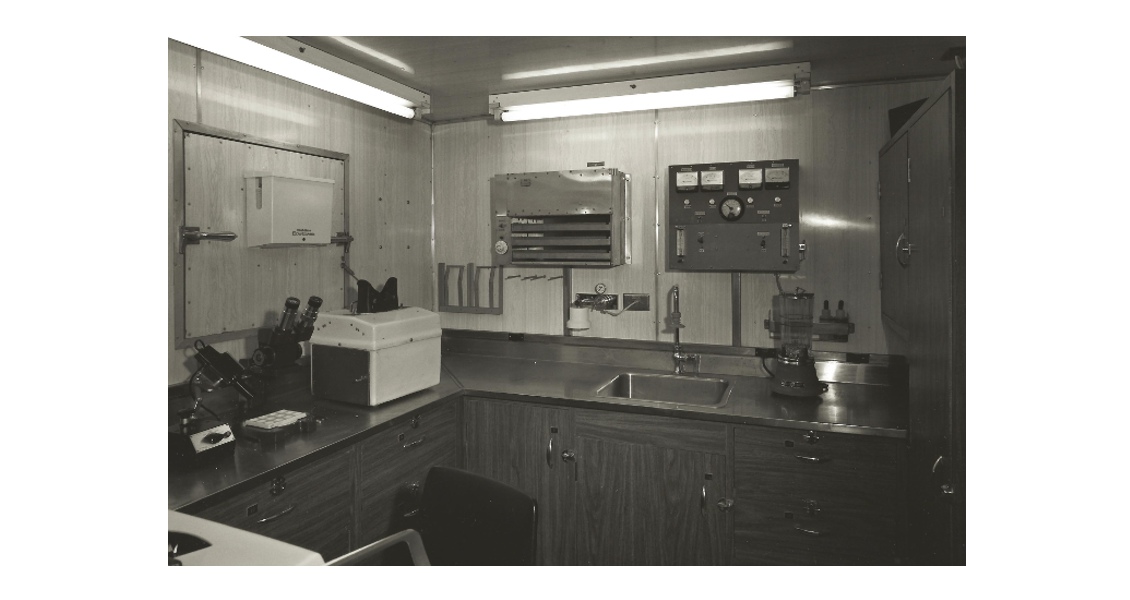

The loggers collect the cuttings from the shale shakers, wash and sieve them to remove any drilling mud and oversized cavings (rock fragments from above the bit). The washed samples are then examined with a microscope for lithological classification and percentages, and under ultraviolet light for indications of oil shows. This analysis is usually done quite quickly, and is dependent on the knowledge, skill and experience of the geologist looking at the sample. As such, it is a subjective, qualitative analysis, which when done by an experienced geologist who is familiar with the local geology can be invaluable.

Over the last few years there has been an increasing interest in using more advanced laboratory analytical methods at the rigsite. Technologies such as x-ray fluorescence and x-ray diffraction give a quantitative analysis of the elemental composition and minerals present in the cuttings sample. Combined with techniques like pyrolysis to analyze the type, origin and maturity of hydrocarbon material in the cuttings, it is now possible to get a detailed quick analysis at the rigsite in order to identify potential zones of interest.

Gas Monitoring

From the earliest days, wellsite geological analysis involved looking for evidence of gas. Once the gas trap came into use, the drilled gas was analyzed with a simple ‘hot-wire’ or Wheatstone bridge detector, which gave a basic indication of the percentage of combustible gas.

Throughout the 1950s and 1960s gas detection improved and by the 1970s gas chromatographs had become compact and reliable enough to be used at the rigsite. Typically methane, ethane, propane, butane and pentane are identified, but this technique can also be used to identify higher weight hydrocarbons. More recently, mass spectrometry is being used in mud logging units, allowing the identification of hydrocarbons as well as other gases such as helium, carbon dioxide, and hydrogen sulfide.

Gas is usually contained in the pore spaces of the drilled rock, the gas seen in low permeability formations such as clays and shales giving a background value. When a more porous, permeable formation such as sandstone is drilled, gas levels will increase if it contains hydrocarbons. This indicates that hydrocarbons are present, but not how much or what kind. However, by examining the ratios of the gas chromatograph data we can identify what types of hydrocarbons are present in the reservoir and also identify features such as the gas-oil contact.

If the mud weight in the borehole is too low to counter the formation pore pressure then gas will travel into the annulus if the formation is permeable enough. There is the risk that in an impermeable formation such as a shale or mudstone the pore pressure can increase above the mud weight. If a permeable formation such as sand is then encountered the fluids within the sand can flow into the well and cause a ‘kick’, which, if not controlled, could result in a blowout.

We therefore need to identify increases in formation pore pressure as quickly as possible. During the 1960s it was realized that there was a relationship between porosity and depth under normal compaction conditions, and that increased porosity resulted in an increase in pore pressure. This resulted in a variety of techniques being developed to analyze the drilling parameters in order to identify changes in porosity and so pore pressure. As the one place on the rig where the geological and drilling information was collected and analyzed, it was natural that pore pressure evaluation became another mud logging service, albeit run by specially trained engineers. Today, pore pressure prediction is a specialist technical discipline using formation evaluation data such as resistivity and acoustic data rather than drilling data, and is usually run by experienced specialists, many of whom started their careers as mud loggers (see GEO ExPro, Vol. 12, No. 1).

Operations Monitoring

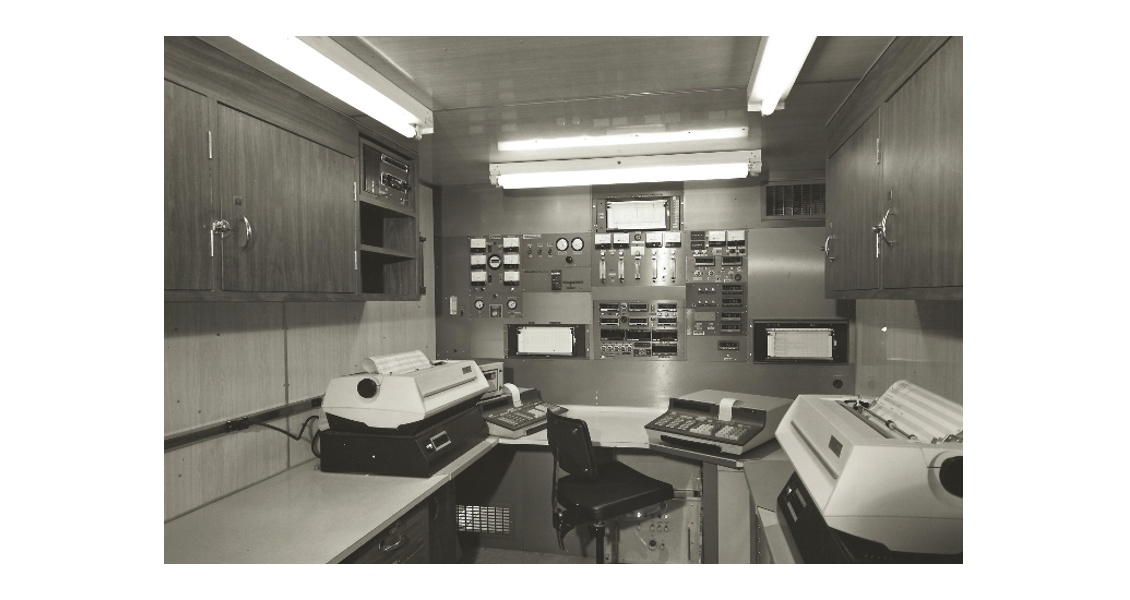

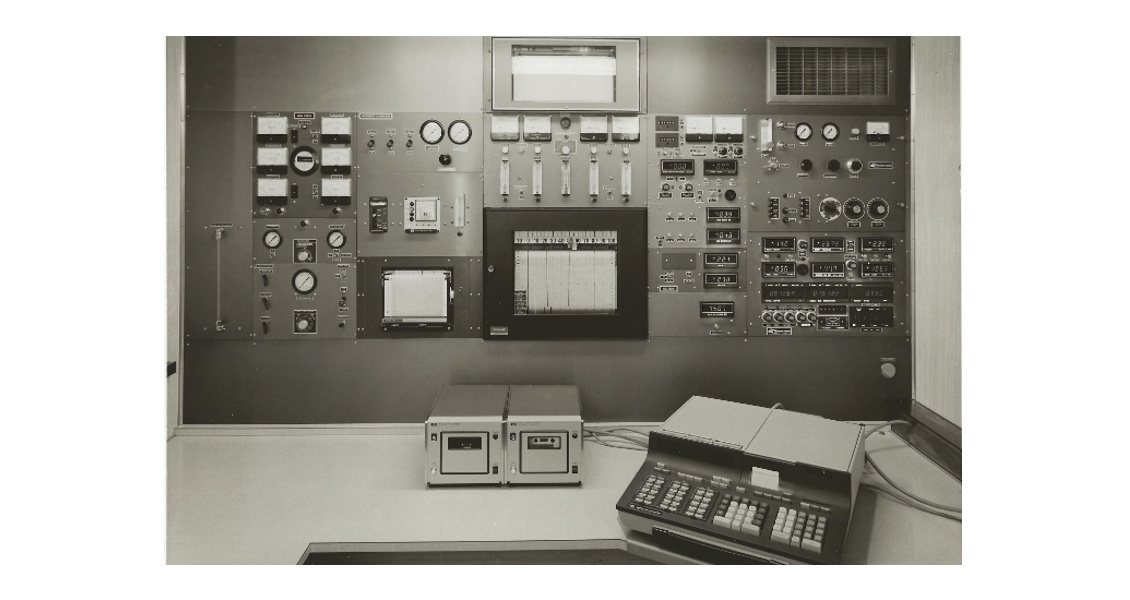

The mud logging unit described by Hayward in 1940 includes instrumentation to monitor the basic drilling parameters: hole and bit depth, rate of penetration and the pump strokes (essential for tracking the lagged samples). These can all be seen in any mud logging unit today, along with drilling parameters such as hook load, weight on bit, surface torque, pump pressure, return flow rate and mud pit levels. The mud logging unit is therefore the one place on a rig where all the drilling and geological information is seen and recorded.

Originally the sensors were simple analog devices such as the block or kelly height sensor which calculated the rate of penetration using pressure changes from a water bottle fixed to the kelly or travelling block hydraulically attached to the drill floor. These basic measurements have now been replaced with more accurate reliable digital systems.

The engineers continually monitor, record and analyze the sensor data. All operations are recorded and displayed both on the rig and back in town. This allows the drilling team to watch operations and identify shifts in trends that could indicate problems.

As operations monitoring has grown it has led to the development of data engineers – experienced mud loggers who have moved from the ‘wet end’, catching, preparing, and examining the cuttings, to the ‘dry end’ of the unit, where they concentrate on monitoring the equipment and operations. Data engineers perform an increasing amount of drilling engineering, running calculations for drilling hydraulics, torque and drag and drilling exponents such as DXc and Mechanical Specific Energy.

As they monitor all the operations on a drilling rig from spudding, drilling, tripping, casing, cementing and testing a well, the data engineers get a far wider understanding of rig operations than most service company engineers. In consequence, they are highly sought after for a multitude of other jobs from mud, application or drilling engineer to company representative.

In recent years the need to reduce the number of people at the rigsite, especially offshore, has resulted in the growth of remote operations. By using high speed data connections a well data engineer can now sit in an office in town or in a client’s remote operations centre working in an integrated team with the client and other service companies.

Safety Monitoring

One of the most important functions of a mud logging unit is safety monitoring. As the unit monitors data from all around the rig, including pit levels, return flow and gas in the mud (toxic gases such as H2S as well as hydrocarbons), mud loggers have always been responsible for spotting potential dangers.

Decreases in either the return mud flow or the mud pit levels could be the first signs of mud losses downhole, while increases could indicate a potential kick. Continuous gas monitoring enables the mud loggers to have the first indications of high levels of explosive or poisonous gas. They must remain vigilant, quickly identify potential problems and inform the driller and company representative. It is therefore a common requirement that the unit is manned continuously.

In conclusion, mud logging is an essential part of any drilling operation, combining practical geology, drilling knowledge and engineering to help ensure a safe and successful well.

In this article, I have shown how mud logging offers a great opportunity to gain a wide knowledge of oilfield drilling and geology and can act as a stepping stone to a range of careers. However, many loggers find a rewarding and fulfilling career within mud logging itself, either in the field, in operations coordination, training or other roles and who bring a wealth of experience to help develop the next generation of oilfield geologists.