Europe is in a dire need of additional gas supplies following the commitment from most countries to cut down on import from Russian gas. This has become even more acute now that Russia has stopped gas supplies to some smaller countries and started to reduce supply to bigger nations on its own accord, despite long-term contracts being in place.

The European Union (ex UK) consumed around 340 Bcm of gas in 2021, with up to 40% (155 Bcm) of that being supplied by Russia. Whilst the UK hardly imports gas from Russia, many countries in the central Europe rely on it to a large extent.

A policy U-turn

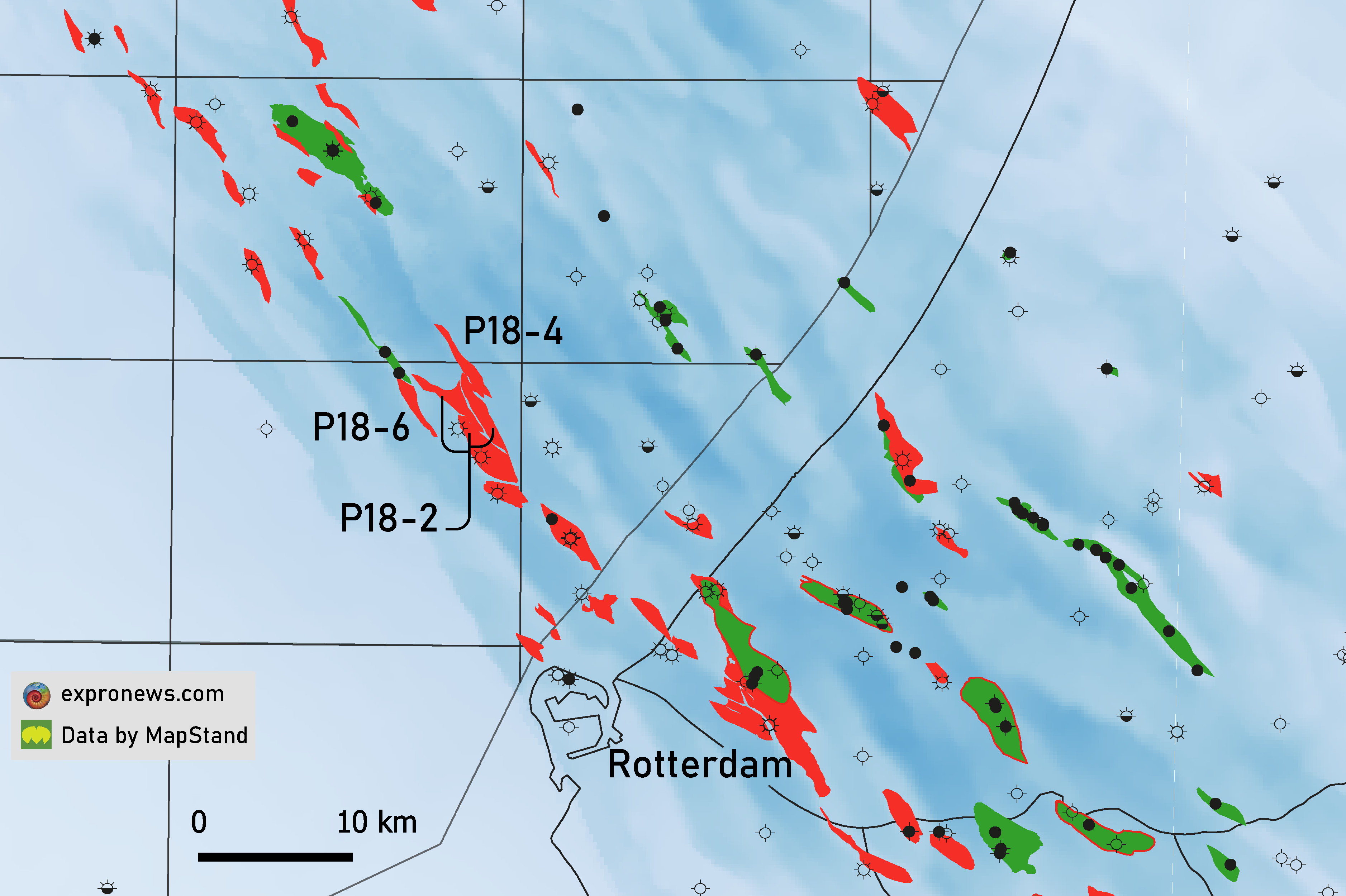

It is because of the threat of gas supply shortages that Germany has already announced a U-turn in its policy not to drill more hydrocarbon wells in the German North Sea. Just a month or so ago, the Germans opened the door to the development of the cross-border N05-A discovery that straddles the Dutch-German median line. Some people argue that there is more room to explore the wider German North Sea sector as well, given its relatively small number of wells being drilled on sometimes poor quality seismic data.

But the N05-A development will not bring much relief. The Rotliegend reservoir may contain around 5 Bcm, but even when nearby prospects come in and the Turkoois discovery comes on stream on top of that, there is no reason to sit back and relax. What is needed is something bigger to step in.

Groningen

There is one field that would allow lowering the amounts of imported LNG significantly and that is the Groningen field in the Netherlands with an estimated reserve of around 450 Bcm. Although Groningen gas will unlikely be making its way to countries like Bulgaria and Poland, households and industries in Germany, Belgium and northern France that have been using Groningen gas for decades are (still) ready to consume it.

The big issue that overshadows the Groningen field is the possibility that induced seismic events will increase in frequency and possibly intensity when gas production is to be ramped up again. It is for that reason that the Dutch government has forced the operator NAM (a Shell/Exxon 50-50% joint venture) to cease production this year.

The geopolitical situation is however changing so quickly that the Dutch government announced yesterday that in the 22/23 heating season no further well abandonments will take place in Groningen. That doesn’t yet mean that production will ramp up, but the door is being kept open.

But what if there is a way to produce Groningen gas without causing an increased risk in earthquakes? A group of subsurface and technical specialists from the Netherlands thinks there is.

Nitrogen injection

The Group Groningen 2.0 proposes to inject nitrogen into the northern part of the field where production has already ceased. By doing so, the reduction in pressure related to production of gas is being counterbalanced by the introduction of nitrogen. This is anticipated to subsequently reduce the risk of induced seismic events. The idea is that the injected gas will ultimately find its way to the south of the field as the years of nitrogen injection progress.

Nitrogen injection is not new

Injection of nitrogen is not a new phenomenon. NAM has been using the technique in the De Wijk gas field in the north of the Netherlands to sustain production for a number of years already. The biggest nitrogen injection project in the world is located in Mexico, where PEMEX started using the gas in 2000 to maintain pressure in the biggest oilfield of Mexico at the time, Cantarell. The project resulted in an increase in production from 1.6 MMbbl/d to 1.9 MMbbl/d in 2002, rising to its peak in 2004 of 2.1 MMbbl/d. However, production rates could not be maintained and began to decline rapidly in the second half of the decade. By 2010 production had fallen to 558,000 bbl/d.

NAM already carried out a feasibility study for nitrogen injection in Groningen in 2012-2013, but the project never came off the ground. At the time, it was envisaged that all remaining 600 Bcm of gas in Groningen was to be produced, which came with a big investment in a nitrogen plant, injection wells all across the field and the construction of nitrogen reinjection units with all production clusters.

Now that production from Groningen has already been scaled back to a few Bcm a year, a nitrogen injection project is much more manageable according to the group. They propose to mostly re-use up to 15 existing wells in the northern part of the field, in which 0.4 to 1 Bcm of nitrogen will be injected on an annual basis. Selection of the injection wells should happen on the basis that they are as far removed from reservoir faults as possible.

Whilst injection would take place in the northern part of the field, the nitrogen front would slowly migrate southwards, thereby pushing methane further towards the existing production wells in this part of the field.

The holy grail?

Is nitrogen injection the holy grail? No, it will not be a quick fix, as testing will need to be carried out to prove the concept in Groningen. That is why the technique will not alleviate pressure on supply this winter. However, given the dire situation with regards to gas supply and the lack of tangible workarounds that do not cause a rapid rise in CO2 footprint such as the transportation and generation of LNG, the project may still deserve a decent look.

HENK KOMBRINK