In the early decades of oil exploration and production, from the 1860s to the early 1900s, the concept of an oil field having clear boundaries was not given much thought. Drilling just radiated away from where the discovery was made to a point where water was the only thing that was found.

Production was, therefore, very chaotic and fast; it was a matter of who pumped hardest. There was no consideration at all of extending licence boundaries vertically down to where the field was, implying how much one could produce. If you didn’t produce it yourself, your neighbour would, so you’d better get on with it. This strategy led to a mad rush once a field was discovered, seriously supporting the boom and bust cycles of the oil industry.

Early oil exploration and production

The first “reservoir engineer” who recognized the need to properly map a field outline with the idea to unitize the volumes of oil allocated to each licence owner was Henry Doherty. He argued that it would enable producers to pump at much more modest rates, which would in turn increase recovery factors and thereby guarantee a much longer economic life of a field.

His peers ridiculed him for a long time. This is more so because he suggested that the state should have ultimate control over this. In the USA, this was very badly received, especially by the smaller explorers, because they just wanted their opportunity to get rich.

But he did ultimately get his way, and today, the first thing geoscientists do when exploring or drilling for oil is to map the outline of a prospect or discovery to calculate volumes and perform an economic analysis.

This was a long introduction to the main topic of this article, Sangomar, but it fits the narrative of what follows.

Sangomar discovery and its implications

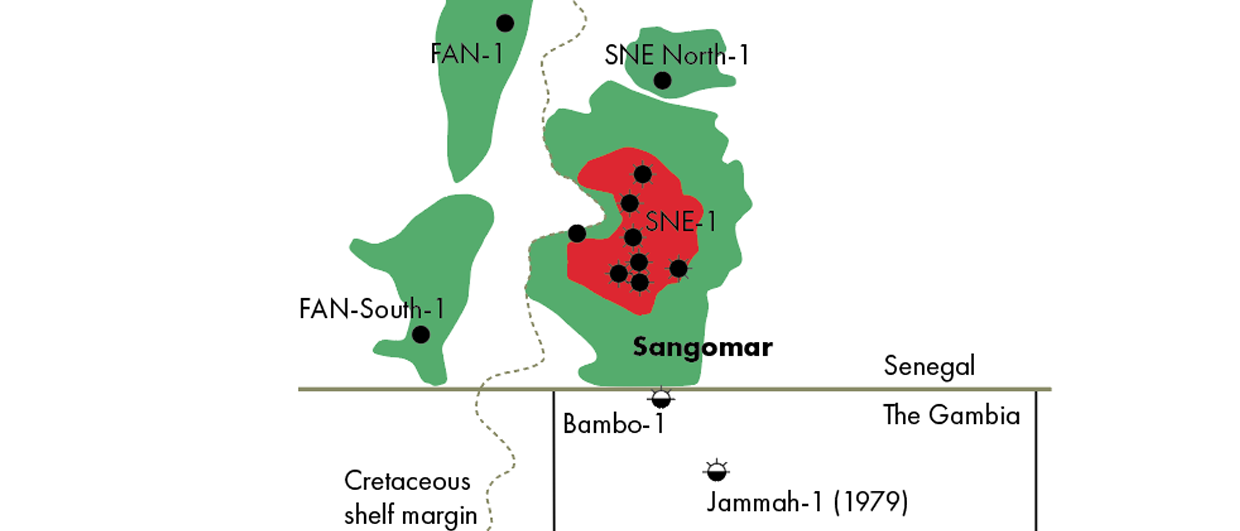

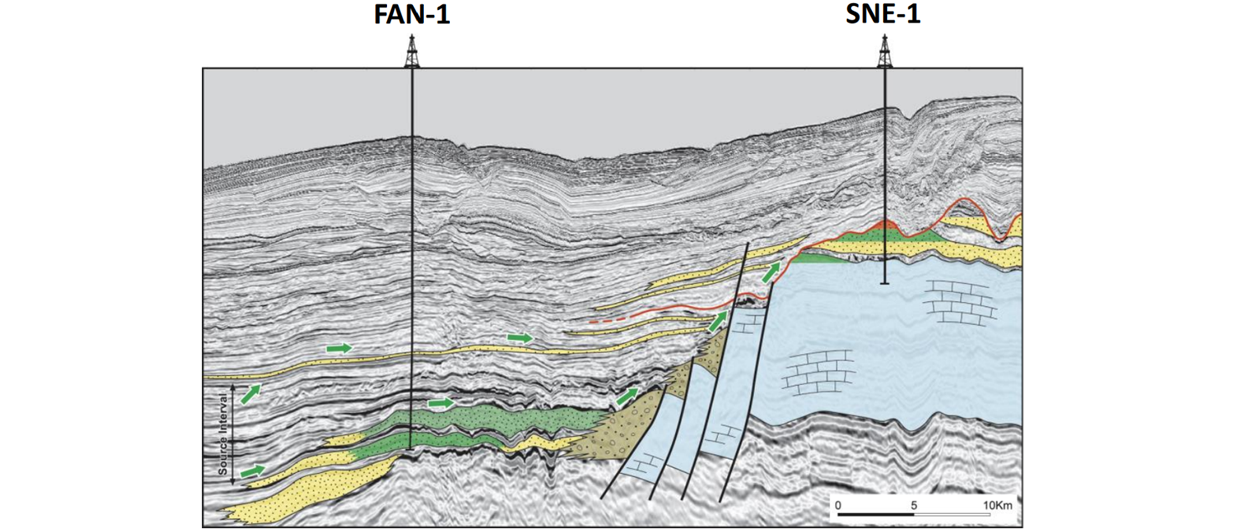

Sangomar was discovered in 2014 in Senegalese waters through well SNE-1, drilled by Cairn Energy (40 %) and partners ConocoPhillips (35 %), FAR (15 %) and Petrosen (10 %). The oil – and gas – are hosted in Lower Cretaceous Albian sandstones in a closure on the Lower Cretaceous shelf edge. Subsequent appraisal wells confirmed the presence of oil and gas and contingent recoverable resources which are now estimated to be around 560 MMboe (2C). The field celebrated its first oil in June this year, and the operator is now Woodside (82 %), partnered by Petrosen.

Being close to the median line with neighbouring The Gambia, it is no surprise that following the discovery of Sangomar, people in The Gambia also started to be excited about their oil potential.

FAR’s exploration and dry wells

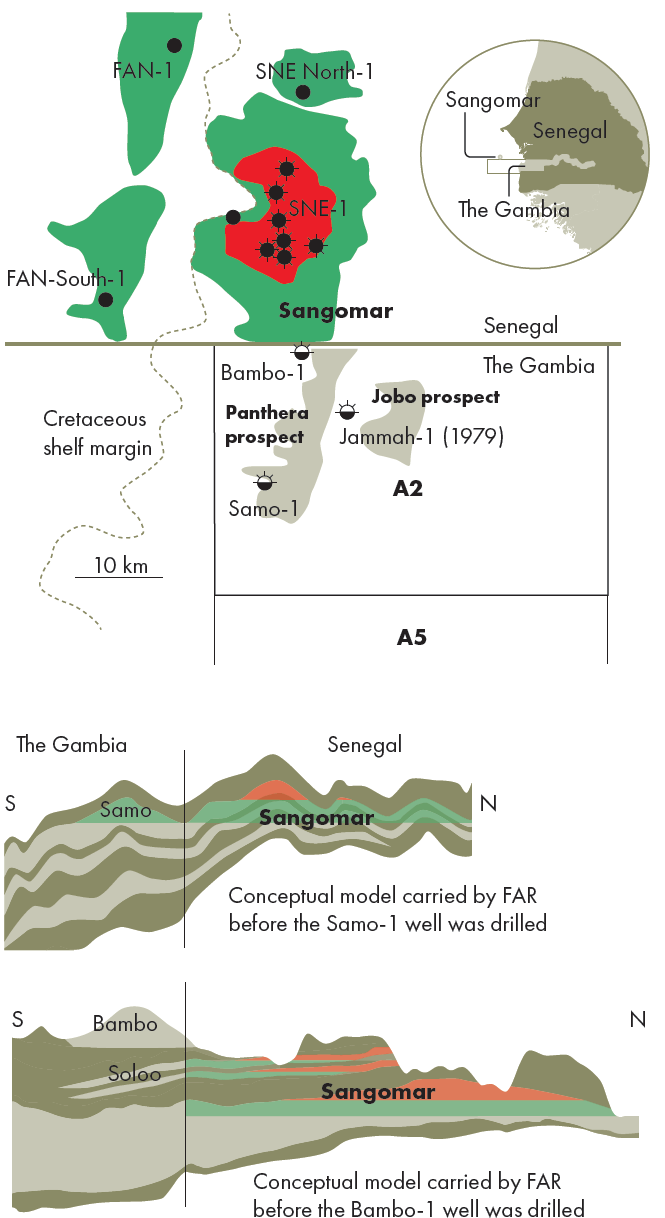

FAR, the Australian company that already had a 15 % stake in Sangomar, saw the potential in The Gambia too, and acquired an 80 % stake in blocks A2 and A5 in 2017. There is little doubt what FAR was after, as in a predrill presentation, Ms. Norman from FAR commented: “You can see clearly that the Sangomar oil fields extend south into The Gambia. In fact, the location of the (planned) Bambo-1 well is 500 meters from the border to the south, drilling into the extension of the Sangomar field that we call the Soloo prospect.”

In fact, the company even seemed to be of the opinion that the Sangomar and Samo structures might share the same contact, potentially increasing the size of the field significantly. It is probably this concept that determined the order in which the two wells that FAR and Petronas subsequently planned in The Gambia were drilled. First, the Samo-1 well testing the potentially biggest price, and subsequently, the Bambo-1 well either to confirm the connection or to test a more modest extension into The Gambia in case the Samo-1 would turn out dry.

However, disappointingly, both wells came in “dry”, with only some shows reported.

The Samo-1 well did find the Upper and Lower Albian reservoir, but deeper than predicted and it also confirmed seal breach as the main factor as to why only some shows were encountered. The same seal breach explanation was subsequently presented to explain a failure at Bambo-1. Even worse, in this case, the reservoir quality turned out to be very poor, in contrast to Samo-1, where it exceeded expectations.

Lack of transparency and speculation on FAR’s decisions

What stands out is the lack of data from the press releases. No well logs are presented, no porosity nor permeabilities given, no pressure points are being mentioned, and the wells were wrapped up very soon after drilling was completed. Seismic data are missing in company updates too; it is only cartoon-like drawings that are being presented. This renders it very challenging for outsiders to see how FAR arrived at this conclusion and whether the right data were obtained to support these claims.

But let us assume that the information shared is correct and that Bambo-1 especially found a poor reservoir with a breached seal. First of all, it would then still be surprising to keep the southern boundary of the field exactly lined up with the median line. Secondly, why would one conclude only on the basis of one well that Sangomar does not extend into The Gambia at all? The depth of the top reservoir has not been presented, and therefore, no map can be produced showing the extent of the now “discounted” area.

There may be more at stake, as Ousman F. M’Bai argues in a reconstruction of the Sangomar exploration history he published in August. In this long read, he points out that FAR sold its 15 % stake in Sangomar in 2020. He also points out that the company has done very little to firm up any of the identified potential in The Gambia in recent years, despite claims that there remains a lot to be found. Combined with the likelihood that none of the current partners in the field were keen on the potential of lengthy negotiations to arrive at a unitization deal, would it be possible that FAR got a good deal for their Senegalese stake in Sangomar in return for keeping a low profile in The Gambia? Ousman has attempted to seek answers from FAR, but has had no response so FAR.

This brings us back to where this story started – the need to properly unitize discoveries. But we can add an element to what Henry Doherty argued for at the time. Making absolutely sure that each country gets its fair share.