This in what a team of researchers concluded in a paper published in the journal Geothermics this year. It must have been a bit of a surprise to find very modest heat flows and no sign of an active geothermal system at all, despite a thick succession of basalts. It wasn’t the oldest basalts either.

Anomalies

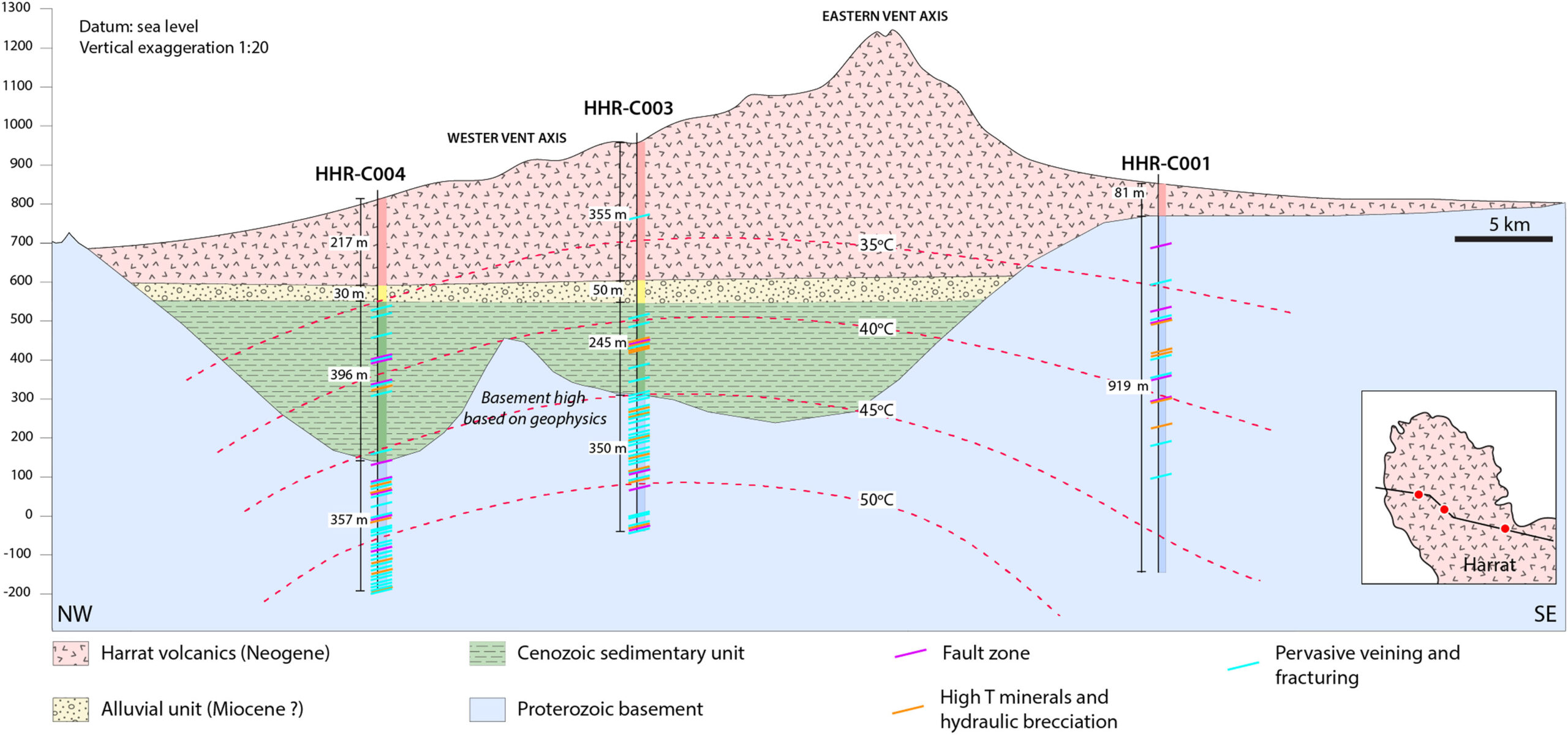

The team drilled a total of three wells to a depth of 1,000 m. The locations of the wells was chosen in such a way to increase the probability to tap into faults and fracture zones that could provide a pathway for convection of geothermal fluids. The presence of a series of high-conductivity magnetotelluric anomalies was also instrumental in locating the wells. Either the presence of a clay cap or the upwelling of hot fluids from deeper strata was seen as an explanation for the anomalies.

THE NORTHERN RAHAT VOLCANIC FIELD

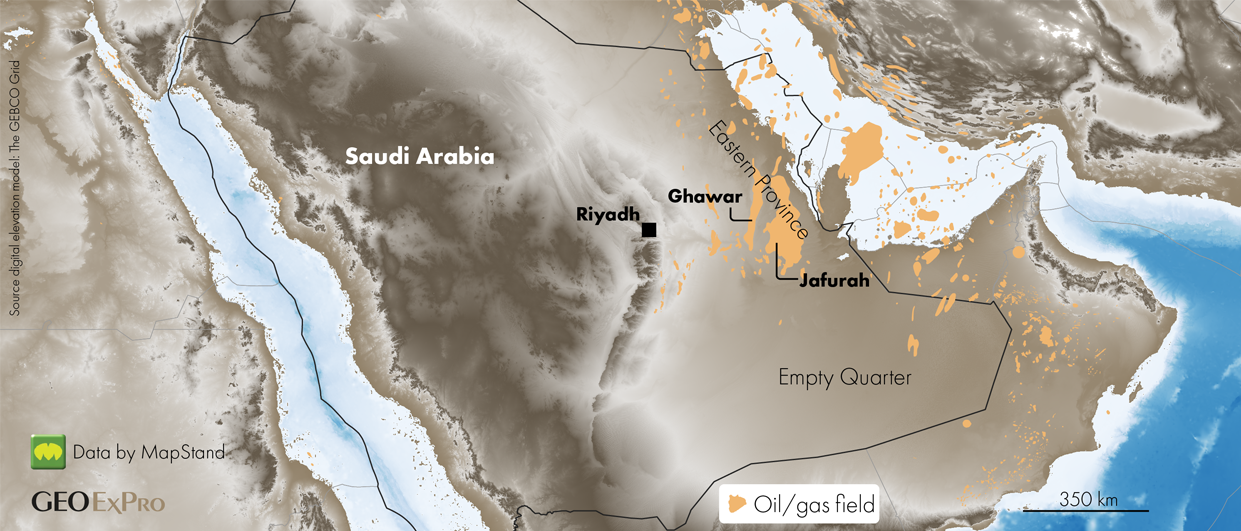

The lava field of northern Rahat is the most extensive of the Arabian Plate, and developed from the Miocene to around 10,000 years ago. Decompression melting associated with the Red Sea spreading centre or upwelling related to a plume have been put forward as explanations for its formation.

Modest results

All three wells fully penetrated the volcanic interval, beneath which a thin Cenozoic sedimentary succession was found before basement was hit. The Cenozoic succession is dominated by fine-grained rocks, overlain by a few tens of meters of coarsed-grained alluvial deposits.

In contrast to what one might expect from a young volcanic system though, the average geothermal gradient found in the wells is low; approximately 22.3° C / km when considering the whole drilled interval, and 20.3° C / km based on data from the basement section only. Higher conductivity of the basement rocks is a possible explanation for this.

The geothermal gradients already provided a hint to the main conclusion of the study; no active geothermal reservoir has been identified in the wells, even though porous and fractured rocks were observed. Normal groundwater conditions prevail, with evidence of an older hydrothermal system given hydraulic brecciation observed in the cores.

The conductive layers observed in the magnetotelluric data probably represent the mudstone rocks concealed beneath the Rahat lavas rather than from clay caps that can sometimes be found above geothermal reservoirs.

The authors conclude that there may still be potential for deeper geothermal projects, but it all seems a little like trying to finish off with some promise whilst the data have clearly suggested that this area does not offer the best geothermal ticket in the country.