The Spanish explorers and conquistadors who came to Mexico in the 16th century saw many oil springs and asphalt deposits there. For centuries, the indigenous people had used asphalt to seal their canoes, for medicinal purposes and as incense in religious ceremonies, and collected blocks of bitumen from beaches along the Gulf Coast to provide fuel for their fires. By the late 19th century, the oil prospects of Mexico were attracting a wider interest. In 1884 a new mining law gave landowners the right to exploit petroleum in their lands but, with a lack of capital and technical expertise in the country, it fell to American and European companies to take up the challenge of exploration.

The Golden Lane

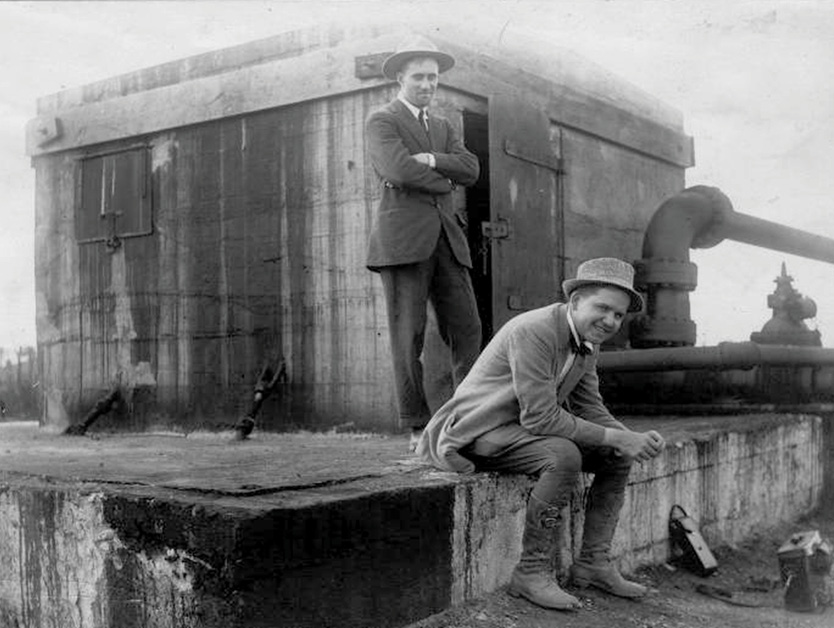

Prospecting began in earnest in May 1900, when oil tycoon E.L. Doheny and his business partner Charles Canfield arrived from California. They had first struck oil in Los Angeles in 1893, triggering an oil boom and enabling them to attract the capital needed for their Mexican venture. With the assistance of Mexican geologist, Ezequiel Ordonez, they made their first commercial discovery at Ebano near Tampico. Over the next few years, operating through the Mexican Petroleum and Huasteca Petroleum companies, they drilled numerous wells in the area. In February 1916, the Azul No. 4 well in dense jungle produced a gusher bigger than the famous Spindletop in Texas, exploding nearly 600 feet into the air and blowing 260,000 barrels of oil on the day it was capped. By the end of 1921, it had produced a total of 57 million barrels of oil.

Meanwhile an English firm, S. Pearson & Son Ltd, was completing a railway in the Isthmus of Tehuantepec, connecting the Atlantic and Pacific coasts. Headed by Weetman Pearson (later Lord Cowdray), the company diversified into the oil business in 1901 after Pearson missed a train connection and was stranded in Laredo, Texas. There he saw at first hand the ‘oil mania’ that was sweeping Texas after the Spindletop discovery. Knowing that oil seepages had been found around the Tehuantepec railway, he cabled his manager to buy up “all land for miles around”. He also employed Captain Anthony F. Lucas, who had brought in the Spindletop well. Although initial results were disappointing, the company switched operations to the area around Tampico and hit a gusher at the San Diego de la Mar No. 3 well in 1908. It was later revealed as part of an aligned group of oil fields known as Faja de Oro, the ‘Golden Lane’.

Incorporated as Mexican Eagle (‘El Aguila’) in 1909, the company made further discoveries at Potrero del Llano No. 4 and Juan Casiano No. 7, bringing a new wave of prospectors, drillers and fortune hunters to Mexico – by 1920, there were 155 separate companies and 345 individual enterprises operating in the country. Tampico was the thriving centre of the oil industry with the ‘Southern Fields’ (the so-called Golden Lane) being the most prolific producer. Next in importance were the ‘Northern Fields’ situated west of Tampico which included Panuco, Topila and Ebano as the main oil fields, but these were not quite so productive.

The third main player, Waters Pierce Oil, was a former affiliate of Standard Oil. It had established a monopoly over petroleum sales in Mexico and moved into the drilling business under its Mexican Fuel Oil brand. In 1913 the company struck oil at Topila, an area that Mexican Eagle had previously dismissed as unpromising. By 1914, Mexico was the third largest oil-producing country in the world and Mexican Eagle controlled about 60 percent of production, expanding into refining, distribution and selling.

The Road to Expropriation

A difficult terrain, climate and lack of infrastructure all conspired against the oilmen. Even when oil was found, the number of high-pressure blowouts remained high. There was a lack of experienced labour, and working conditions were poor. The American geologist Everette Lee DeGolyer, who worked for Mexican Eagle between 1909 and 1919, noted the predicament of Mexican workers:

“Men came down from the hills, brought a meagre supply of food with them, worked for a few days, slept in the brush, received their wage and went back to their homes. Skilled labour, almost altogether American drillers, their helpers, mechanics, and engineers, on the other hand, were properly housed, well fed, received medical attention, were paid a higher wage than at home, and generally received superior treatment.”

During the Mexican Revolution (1910–1918), rebels occupied Mexican Eagle oil camps and workers were killed. In the face of threats to foreign oil workers, DeGolyer was forced to evacuate in April 1914, returning in October to compile a report on the geology of the Mexican oil fields, although the revolution rumbled on.

In 1917, article 27 of a new constitution restored ownership of the subsoil to the state, although this was amended in 1928 by the Calles-Morrow agreement which allowed the oil companies to retain the rights they had previously held. By then Mexican Eagle was a subsidiary of Royal Dutch Shell, with the remaining share of the country’s oil business dominated by US majors such as Jersey Standard and Standard Oil of California. More than 4,300 oil wells were drilled between 1920 and 1929, contrasted with the 442 drilled during the preceding 20 years.

In the 1930s, the Great Depression and a glut of oil on the global markets saw prices tumbling; government revenues fell, and labour unrest followed. On 18 March 1938 President Cardenas signed an order expropriating the oil industry, effectively nationalising the assets of the foreign oil companies. Shell and Jersey Standard led an international boycott and a battle over compensation that lasted several years. Although agreement was reached, the oil companies were not allowed back into Mexico and oil operations were exclusively managed by the state oil company, Petroléos Mexicanos (Pemex). Many firms moved to Venezuela, where conditions were more favourable.

The Mexican Oil Boom

With technological advances in marine drilling, it was inevitable that exploration would go offshore. Pemex drilled its first offshore wells in the 1950s, but the breakthrough came in 1972 when a fisherman named Rudesindo Cantarell Jimenez led Pemex geologists to a location some 50 miles off the coast in the Bay of Campeche where an oil slick had fouled his nets. Named Cantarell after the fisherman, the supergiant oil field was hailed by Mexican officials as ‘el salvador del pais’, the saviour of the country.

The Cantarell field was formed from carbonate breccias deposited by a massive asteroid impact which created the Chicxulub crater – an event that scientists believe caused the extinction of the non-avian dinosaurs some 65 million years ago. The complex comprised four oil fields, the largest being Akal (named after a Mayan god), which held about 90 percent of the reserves.

Offshore drilling brought its own risks. Tropical storms and hurricanes could disrupt production, as well as blowouts and fires. In June 1979 the Ixtoc I platform exploded and, at the time, caused the largest oil spill in peacetime. This was an exploratory well being drilled in the Bay of Campeche and resulted in almost 3.3 million barrels of oil escaping into the sea before Pemex could plug the leak. A harbinger of the more serious Deepwater Horizon disaster in 2010, its environmental impact was wide-ranging and local industries, especially fishing communities, were hit hard. “The amount of fish to catch was never the same as before the spill,” remarked one fisherman.

The 1970s and 80s witnessed the dominance of OPEC (the Organisation of Petroleum Exporting Countries), when oil embargoes and price shocks hit the global markets. In search of energy security, the United States turned to non-OPEC countries like Mexico as alternative energy sources to the Middle East. The Mexican offshore discoveries brought an oil boom to meet this demand. Between 1977 and 1981, the country’s petroleum output rose from 400 million barrels to 1.1 billion barrels.

Mexico was rapidly transformed from an importer of oil to one of the world’s leading petroleum exporters, with the promise of massive growth in the future. President Portillo used burgeoning oil reserves as collateral for massive foreign loans, most of which were reinvested in Pemex. But when the United States raised interest rates, a debt crisis followed, together with a succession of economic blows that saw Mexico’s oil production stagnate until the mid-1990s – only then did it regain its 1982 level.

The Long Decline

The Cantarell complex reached a peak of about 0.8 billion barrels in 2004. Gas pressure in the reservoir accounted for its remarkable oil flows but, when that declined, production rates dropped. Pemex used various enhanced oil recovery (EOR) techniques such as nitrogen injection to increase yield from the exhausted field. In 2004, output suddenly revived to an astonishing 2.1 million barrels per day; however, this was a momentary blip and production dropped back to 10 percent of its peak.

The KMZ development adjoins Cantarell and was discovered between 1980 and 1991. Its name is an acronym of the three main producers – Ku, Maloob, and Zaap – in a five-field complex of 207 producing wells. In 2007 a floating production storage and offloading (FPSO) vessel, the Yuum K’ak’nab, was added to the field, the first of its kind in the Gulf of Mexico. KMZ’s output peaked at 900,000 bopd in 2016 and has since fallen to 784,000 bopd, which accounts for 46.5 percent of Pemex’s total production.

Meanwhile, back on land, Pemex had made steady progress. It struck oil at a depth of 13,775 feet beneath the jungle in the Reforma area of Tabasco State in 1972. After mapping and petroleum systems analysis, between 125 and 150 potential oil prospects were identified, and many of these went on to become prolific producers. By 1979, 96 out of 216 wells were producing oil, although some of those suffered from reduced pressure. Other discoveries were made in the Chicontepec and Sabinas Basins, and the largest onshore unit was the Samaria-Luna oil field in the south which was producing 145,000 bopd in 2015.

Overall, output was in decline. The smaller fields could not make up the shortfall entirely, even though new fields had come on stream. There was a lack of refineries to process the heavy oil known as Maya crude produced by the two main offshore fields. Much of it was sent to the US Gulf Coast refineries and then exported back to Mexico as petroleum products for domestic use. By 2016, increasing domestic demand had returned the country to the status of net importer of refined petroleum products.

In 2014, under President Nieto, reforms allowed competition from foreign private oil companies, with the result that international companies began exporting oil to Mexico, as well as prospecting for oil. Today, Mexico is ranked 14th among the world’s leading oil producers.

A New Perspective

The Eagle Ford shale play extends into Mexico where it is known as the Burgos Basin. According to an Energy Information Administration (EIA) assessment of 2013, it had technically recoverable shale resources of 545 trillion cubic feet (Tcf) of natural gas, and 13.1 billion barrels of oil and condensate. Pemex has drilled some 20 exploratory shale gas wells, but progress has stalled. President Obrador promised to ban fracking soon after his election in 2018, but a recent cold-weather crisis was a reminder of Mexico’s energy dependence on the United States, and Pemex has included shale exploration in its future projects “in the event that policy may change”.

Thanks to Peter Morton for his kind assistance.