All change! All change!

The energy transition is affecting all we do, be that in industry, academia or government. It is no longer a question of whether we need to act, but what we should do and how quickly, driven by the science, as well as public and market sentiment, as the scale of the challenge becomes apparent. Energy delivery, in all its forms, relies on geoscientists and engineers, whether to maintain oil and gas supply and ensure energy security in the near to medium term or to play a pivotal role in the removal of atmospheric carbon, delivering carbon sequestration (CCS/CCUS) and providing assurance it will stay sealed in the subsurface for millennia. Geoscientists also have a critical role in delivering sustainable resources, be that conducting site surveys for wind farms or subsurface characterisation for the future expansion of geothermal energy. All this activity will require a huge growth in exploration and development of strategic mineral resources, providing raw materials for many energy types, from batteries to nuclear energy.

But where will these geoscientists and engineers come from? Is there a strategy to attract and train them? Or are we sleepwalking into a looming crisis in education?

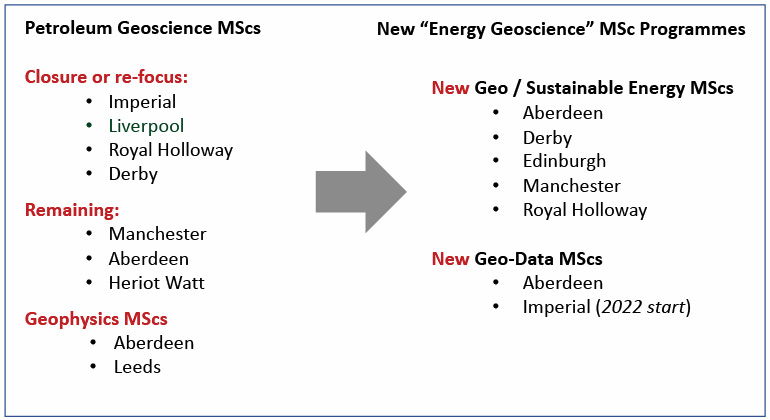

The feedstock for geoscientists into industry in the UK and globally has typically come from master’s programmes, but most of these MSc courses are struggling. In the UK we have seen many petroleum geoscience and engineering courses close (Figure 1).

Those that survive have significantly reduced student numbers. And this is mirrored across the globe, be it in South East Asia where established MSc programmes in Thailand and Malaysia are teetering on closure, with single digit student numbers, or Australia and the US, where closures and course cutbacks are also ongoing apace.

There is a looming disconnect with potential demand for trained geoscientists and engineers for traditional and renewable resources, and the ability of academic institutions to supply.

Delivering the Right Skills

Traditionally in the UK, master’s courses (12-month intensive postgraduate courses) have delivered focused, applied training to students to equip them with the knowledge and skills to join the job market, forming the backbone of the energy industry. But this pipeline of skilled geoscientists is under severe challenge from several fronts. Applicants to UK MSc programmes in subsurface geoscience have been steadily falling for the last five plus years. This reflects several possible causes.

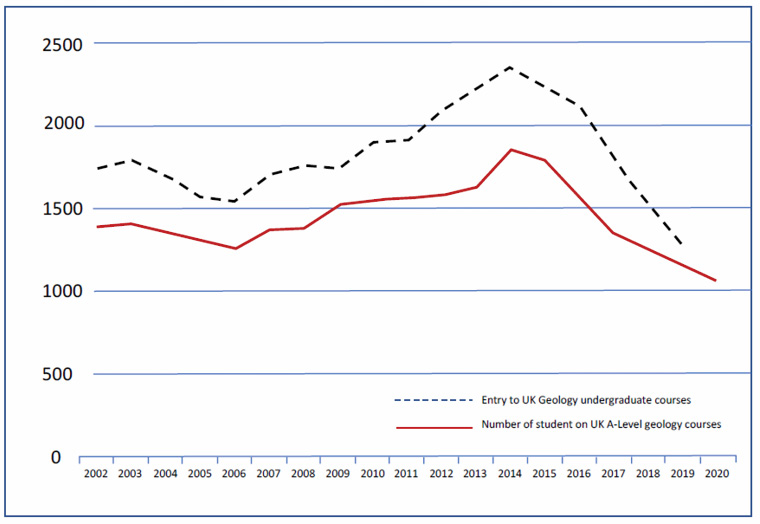

In part, it is a function of a wider issue for geoscience. The numbers applying as undergraduates have also been falling, with UK students studying geology at university declining year-on-year since 2014, a total drop of 43 percent (UK Geoscience UK Resources). This reflects the fact that geology is rarely now taught as a separate subject in schools, instead being introduced only in other associated sciences like chemistry and physics (Figure 2).

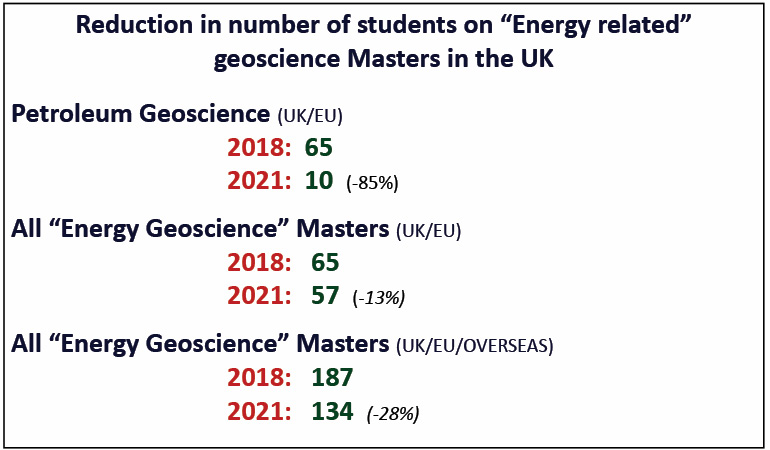

The conversion of UK undergraduates to master’s programmes in energy geoscience and other sciences is worryingly low, with a notable drop in applications. The total number of students on all energy-related master’s geoscience programmes in the UK has fallen by 28 percent over the last three years, with a fall in 85 percent on petroleum master’s, reflecting in part the closure of programmes (Figure 3). In 2021 there were only 10 UK students studying petroleum geoscience at MSc level in the UK.

Cause and Affect

Cost and availability of scholarships is a key issue. After three years of building undergraduate debt, the extra financial commitment to undertake an MSc is considerable. A decade ago, there were a range of funding opportunities to support MSc students, such as scholarships from industry, government (NERC) and from organisations like the Petroleum Exploration Society of Great Britain (PESGB). This attracted the best to apply. However, most of these scholarships have been withdrawn, as companies and government cut costs.

The perception of the job market is another important factor. Students no longer feel there is the prospect of a long, interesting and lucrative career in this field. In the past, the track record of employment for MSc graduates from most courses was very high. The majority joined the oil and gas industry, some went on to undertake a PhD, or moved into other rewarding careers. All benefitting from the broad range of transferable skills taught. Even today our courses have an enviable track record in this regard, but the recent period of low oil price and significant turmoil and redundancies in the sector, reported across the media, has hit student confidence in the energy industry as a long-term stable and attractive employer. Sectors such as IT, banking, civil engineering and environmental consultancies are all perceived to offer better employment prospects. So, there are bridges to build to communicate the exciting opportunities that still exist and to attract the best workforce.

And finally, there is wider public perception of the industry, driven by a media that often only portrays oil and gas companies as polluters, the target of many who put the blame firmly on the energy industry for climate change. An industry only regarded as the ‘problem‘ and not part of the ‘solution’ is not one that graduates want to join. This view is widely held, and whatever those of us who work in energy may wish, it is a strong driver in reducing applications, and something that needs to be countered.

Evolving to Meet the Transition

How can we meet these wide-ranging challenges? To date, only three Petroleum Geoscience MSc courses remain in the UK, at Manchester, Aberdeen and Heriot Watt universities. These are bolstered by strong overseas demand, but all have smaller class sizes and falling numbers of UK applicants. Some courses have already closed and other MSc courses have re-branded and are re-focusing on a broader geo-energy or geoscience and data science curricula (Figure 1). This reflects changing student demand and the need to prepare students for new roles in industry. But the challenge remains to deliver the graduates that industry will need, with the right geoscience skillset.

Collaboration is Critical

To meet future demand and to ensure the UK remains a global centre for geoscience and engineering excellence in subsurface energy requires a collaborative effort. Industry, academia and government must work together to change perceptions, improve communication, deliver innovative training solutions and step-up to lead in the search for resources globally. Recognising this, the Centre for Masters Training in Energy Transition (CMT) was founded in 2020. The CMT is an independent, international organisation and a world leader promoting geoscience training for the energy transition. Leveraging global outreach and working closely with industry, we plan to change the way we communicate and offer a platform for change. We will develop innovative modular online master’s courses that will appeal to students across the world and will also open opportunities to those early career employees who, via distance learning, can continue their education in parallel with their employment. Truly collaborative programmes, in which each participating university would offer a selection of modules, enabling students to create their own bespoke master’s degree.

Global Communication

We need an integrated strategy for communication. Not just talking to ourselves or those already knowledgeable about the issues, but engaging directly with young people using social media and championed by relevant role models. And we need to show we are all part of a collaborative effort to meet the climate change challenge, to be seen as part of the ‘solution’, emphasising the needs of energy security and sustainability, and noting that different parts of the world are at different stages along this energy transition journey.

We need to capture students’ enthusiasm and show them they can look forward to exciting career opportunities worldwide across the evolving energy sector. The CMT is also focused on meeting the demand from industry to re-train its existing staff for the acceleration of the energy transition and to deliver the skilled graduates for research and development.