In line with the UK and Ireland, the Isle of Man, a self-governing British Crown dependency lying in the Irish Sea, has committed to achieve net-zero carbon emissions by 2050. However, while the transition to renewables is taking place, the Island will remain dependent on hydrocarbons for electricity, heating and transport, and until an economic solution is found for energy storage, there will be a continuing need for gas as a back-up due to the intermittent nature of renewable energy generation.

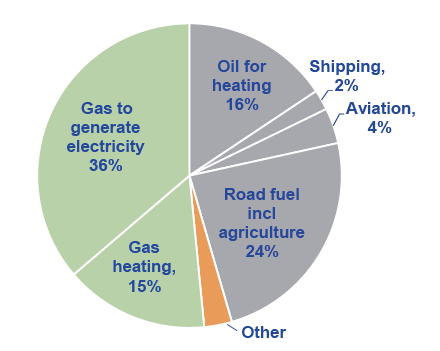

Right now, 97% of the Isle of Man’s energy comes from oil and gas – and every molecule is imported. With only minor contributions from hydroelectricity, energy from waste, biomass and imported electricity, it therefore has a long journey ahead in the energy transition.

The Economics of the Energy Transition

The gas required for heating and electricity generation in the Isle of Man is currently imported through a link into the Scotland-Ireland ‘Interconnector 2’ pipeline. As well as being expensive, the carbon footprint of imported gas – much of the gas being delivered originates in Russia – is obviously significantly more than that of locally produced natural gas. For example, it has been estimated that Russian gas imported to Ireland creates 34–38% more greenhouse gas emissions than using Irish gas, while LNG from Qatar, which is also a supplier, creates 22–30% more emissions as a result of losses and transport required en route. In addition, being dependent on foreign gas, the Isle of Man and Ireland would find themselves literally at the end of the pipeline should gas supplies be disrupted.

The discovery of local natural gas could provide energy security to the Island and also offer an additional local supply for Ireland, as Manx natural gas could be exported there through the very same pipeline that is currently used for gas import.

Using local natural resources is therefore not only good for energy security but also for the environment and jobs.

The Irish Taoiseach (Prime Minister) recently said, “Recognising that we end exploration for oil in Irish waters, we will continue to explore for natural gas given that it’s a transition fuel that we are going to need for the next few decades, as new technologies are developed and deployed.”

Manx Gas Needed

The transition to renewables is clearly an enormous task, requiring time and an investment of several hundred million pounds or more. With a strong demand from Ireland for Manx natural gas in addition to local demand, the Isle of Man could follow Norway’s lead and use the tax revenue from sales of any gas found in its territorial area to fund the required infrastructure and provide subsidies if necessary. This opportunity has been recognised by the Isle of Man government, with Chief Minister, Howard Quayle, recently stating “…should there be enough gas found in our waters, then any income stream from that money should be put aside for the building of a green renewable energy source for the Isle of Man”.

Luckily for the Isle of Man, there could be a significant source of natural gas within Manx territorial waters. In 1982, BP drilled an exploration well off the Island targeting Triassic sands as an analogue to the Morecambe Bay gas fields. Although these sandstones were disappointingly water-wet, the deeper Permian sandstones contained a 50m column of gas in 220m of gross sand, in a similar sub-salt play to those seen in the Permian Rotliegend sandstones of the southern North Sea. In the 1980s and 1990s, the economics of a stand-alone gas development in the Isle of Man were not as attractive as they are today, so in 1996 BP relinquished the acreage, which has sat undeveloped until now.

Offshore Geology Isle of Man

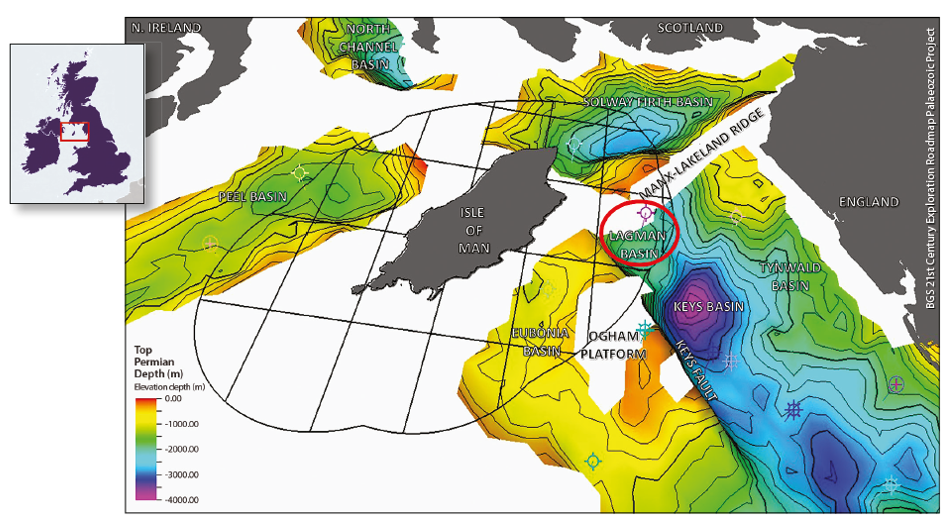

The offshore waters within the Isle of Man’s 12 mile (~19 km) territorial limit contain four main basins: the Solway and Peel Basins located to the north-east and west of the island; and the Lagman and Eubonia Basins to the east and south-east. The structural history of this region is relatively complex. Initial compression during the Caledonian Orogeny created a major north-east to south-west suture as the micro-continent of Avalonia collided with Laurentia, closing the Iapetus Ocean. North-west to south-east extension caused the opening of the Peel and Solway Basins to the north and the formation of major north-east to south-west trending faults that inherited the underlying Caledonian trend. Further reactivation of these Early Carboniferous structures occurred during the Variscan Orogeny, causing inversion structures to form parallel to the Eubonia-Lagman Fault System and along the Solway and Peel Basins, as is evident through the presence of the Manx-Lakeland Ridge.

During the Permian and Triassic, eastwest extension formed the Eubonia and Lagman Basins, segmented by a series of north-west to south-east en-echelon faults, including the main bounding Keys Fault. The Eubonia and Lagman Basins formed part of the larger East Irish Sea Basin graben system, with sedimentation continuing until the Jurassic.

Uplift occurred in the Palaeocene, associated with opening of the Atlantic Ocean and with the input of lavas, which form a series of north-west to south-east-trending dykes that are found across the Isle of Man. This uplift continued due to the Alpine Orogeny, creating inversion anticline structures along with hanging wall blocks in the Solway Basin. In the Eubonia Basin, evidence for inversion is shown by the appearance of the Ogham Platform.

The Isle of Man

Isolated in the Irish Sea equidistant between England, Scotland and Ireland as the glaciers of the last Ice Age retreated, the Isle of Man has a rich history and distinctive culture and heritage. Populated originally by Celts, Manx Gaelic was the everyday language of the people until the 19th century, although the last native speaker died in the 1970s. Vikings arrived in the 8th century, first to raid but then to settle and rule and their burial mounds are a feature of the modern landscape. They established the Manx parliament, Tynwald, which is the oldest continuous parliament in the world.

In the 13th and 14th centuries control of the Isle of Man passed regularly between the warring nations of England and Scotland, settling permanently with the English Crown in the 15th century, and government over the years gradually evolved to the present democratic system in which the island is a self-governing British Crown dependency with the British monarch as nominal head of state. Its inhabitants are British citizens but it is not part of the United Kingdom, although closely allied in governance, international affairs and security. Nor is it a member of the European Union, and the island has used this unusual political status to develop a low-tax economy based around insurance, gaming, IT and banking. It is also home to the annual Isle of Man TT motorcycling races, in which bikers approach speeds of 200 km as they negotiate the tight bends and steep climbs of the mountains.

With dramatic rugged cliffs, beautiful beaches, outstanding natural scenery and over 40% of its land unpopulated and uncultivated, the Isle of Man, which is 52 km long and 22 km at its widest point, is a popular tourist destination. In 2016 it was awarded status as a UNESCO Biosphere, recognising its plethora of diverse natural habitats and unique culture.

Plenty of Potential Hydrocarbon Reservoirs Isle of Man

Current exploration is focused on the Lagman Basin, which is an uplifted terrace of the Keys Basin lying to its south-east: a proven hydrocarbon-bearing province. The Lagman Basin benefits from close proximity to the main kitchen of the East Irish Sea Basin in the Keys Basin, where Namurian deep marine shales act as the source rock.

The main play is the Permian Collyhurst Sandstone, which is at shallower depths here than in the Keys Basin, and should therefore act as a more effective reservoir with preservation of better porosity and permeability values. The area is highly structured due to folding of the Carboniferous strata, fault reactivation and unconformities related to the Variscan Orogeny.

Permian-age halite is found in the St Bees Evaporites, which provides an effective seal to the Collyhurst sands. It is present across all Manx waters, except on highs such as the Manx- Lakeland Ridge. There are also potential Carboniferous reservoirs at deeper levels which have not undergone as much Palaeozoic to Mesozoic burial and Cenozoic uplift compared to the Keys Basin. Further analysis is required to confirm this play. The Ormskirk Triassic play, which is commonly hydrocarbon-bearing in the East Irish Sea Basin, was found to be water-bearing at the 1982 well location, but could be prospective elsewhere in the Lagman Basin.

The Story So Far

In 2014, a small group of Manx-based oil and gas professionals recognised the size of the prize for both the Isle of Man and investors and formed Crogga Ltd. Then, along with supportive residents, they promoted the opportunity to the Isle of Man government. Using venture capital funds raised on the Isle of Man, Crogga Ltd applied for and were awarded a production licence in a 2017 competitive licence round.

Since the licence award, the results of additional technical work have been encouraging. Further mapping of the legacy 2D seismic data has confirmed possible reserves of over a trillion cubic feet of gas in the Collyhurst reservoir with considerably larger upside potential in the Permian, Triassic and Carboniferous. More detailed analysis of Permian reservoir core data from the 1982 BP well shows porosities of 8–12% with permeabilities in the 0.3–0.6 mD range. With water depths between 10m and 30m, and with the Permian reservoir at a depth of about 2 km, the appraisal and development of the field should be straightforward and cost effective. After liaising with all relevant environmental groups, commercial fishing organisations and the UK government, a 360 km2 3D seismic survey is planned for 2020. Planning has also commenced for exploration and appraisal drilling, which it is hoped will occur in 2021.

Should the appraisal drilling campaign be successful, field development activities could follow. One option is a sub-sea development with a pipeline connecting directly to the Isle of Man that will allow natural gas to be used locally for generating electricity and heating. Any remaining natural gas could be exported through the existing interconnector pipeline to Ireland, with the Isle of Man government benefitting from the tax revenues.

Local natural gas will provide energy security for the Isle of Man and a cleaner alternative to oil and imported gas during the transition to renewable energy.