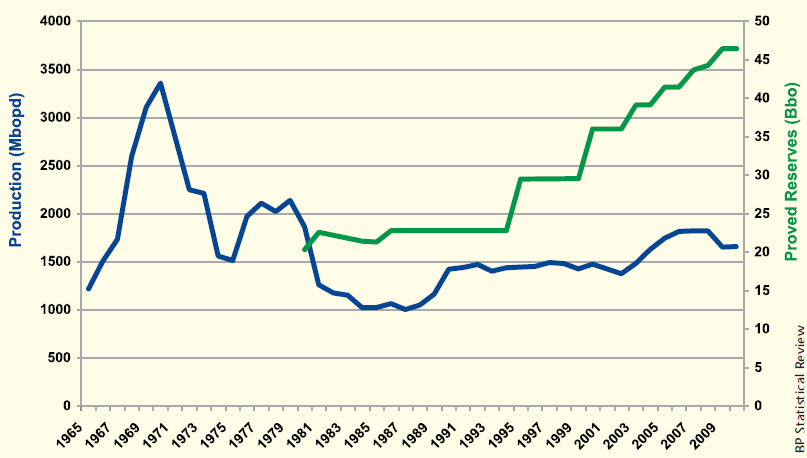

According to the BP Statistical Review, Libya’s proved oil reserves at the end of 2010 stood at 46.4 Bbo, with 54.7 Tcf of gas, some 3.4% and 1.7% of the world’s total respectively and the highest volume in Africa. The same source states that in 2010 Libya’s oil production was 1,659 Mbpd, higher than the 1,470 Mbopd production quota set by OPEC, with 99.4 Bcf of gas, but virtually all production stopped after the imposition of UN sanctions in March this year. Reportedly, only three tanker loads have been shipped since then. Libya therefore has a long haul ahead of it to rebuild the only major source of wealth for the country, which, according to the International Monetary Fund, accounted for over 95% of export earnings, 25% of GDP and 80% of government revenue in 2010.

A Chequered History

Geological surveys in Libya began under the auspices of the Italian National Academy in 1931 with an expedition led by Ardito Desio, which traversed the country from the coast to the Sudan border and back. Four years later, in consultation with other Italian geologists, he reported that there was little expectation of finding oil in commercial quantities in the country.

After WWII, and following the discovery of oil in Algeria, active exploration began in earnest in Libya in 1953. The first discovery well was drilled in the western Fezzan, in the south-western part of Libya, and the first commercial discovery followed three years later in 1959. By 1961 the first oil flowed by pipeline from Esso’s concession at Zelten in the Sirte Basin to its export facilities at Brega. Other companies rushed to the country and by 1965 Libya was the world’s sixth largest exporter of oil.

Very rapidly, Libya went from being one of the poorest nations in the world to a very rich one, based on average per capita GDP. But ordinary Libyans felt that little of the new wealth was filtering down from the elite, and so when a military coup, led by the 28-year-old Colonel Muammar al-Gaddafi, deposed the Libyan king in 1969, it was met with popular support. Gaddafi wanted to build a socialist state and in 1970 the National Oil Corporation (NOC), which had been established two years earlier, was nationalized; by 1973 it had assumed control of exploration and development, production, refining, processing and marketing. Oil production, which had peaked in 1970 at over 3 MMbopd, began to decline, and in the mid-80s dropped to about 1 MMbopd as the effects of the US embargo on trade with Libya, put in place as a result of Libya’s support for terrorist organizations, were felt.

UN sanctions on trade with Libya, enacted in 1992 after the Lockerbie plane disaster in which the Libyan government was implicated, also restricted oil exports. When they were lifted in 2003, followed by the raising of the US embargo the following year, investment in the Libyan oil industry by foreign oil companies increased and production and exports began to creep up, reaching a peak of 1.82 MMbopd in 2007.

There was considerable investment in exploration during the period 2005 to 2010, mainly by foreign companies, but also by the Libyan government, yet the results were disappointing, possibly because the authorities preferred to concentrate on the rehabilitation of existing fields. The difficult fiscal régime also meant that foreign companies were not encouraged to undertake major exploration. In fact, last year some of the exploration companies petitioned the NOC, saying that without a downward revision of tax investment, exploration would cease.

Production Increasing

With an end to hostilities, how long before average Libyans can begin to see something from the bounty that lies beneath their ground?

Many of the wells were turned off when most expatriate workers left in March, but a number have begun pumping again, though progress will of necessity be slow. Many fields were mined or deliberately damaged, while others, such as the older wells in the Sirte Basin, which require water or natural gas injection to maintain pressure in the reservoir, have suffered from months of neglect.

Although foreign workers have yet to return in any significant number, production, which was down to 45,000 bopd in August, is increasing and by mid-November had already exceeded 600,000 bopd. It is set to rise to 1 MMbopd within a few months, and, if the Chairman of NOC is to be believed, to 1.5 MMbopd by the end of next year. And gas has started flowing again from the offshore fields, with Eni announcing in early November that it had restarted production from Bahr Essalam, 110 km north-west of Tripoli, one of the largest gas fields in Libya, which was closed down at the start of hostilities in February.

Libya has five domestic refineries, with a combined capacity of 378,000 bopd, all of which were damaged to some extent during the fighting. NOC have reported that the Az Zawiya refinery in north-western Libya is ready for operation and has received its first post-conflict shipment, while Ras Lanuf on the Gulf of Sirte, the largest Libyan refinery with a capacity of 222,000 bopd, should also be up and running soon.

There is a lot of interest in the prospect of being a part of the new Libya, and several countries have begun moves to cooperation – in fact, a group of French companies arrived in Tripoli to meet officials of the Transitional National Council a week before Gaddafi’s death. Countries which participated in the NATO-led air support during the revolution hope that they may be considered more favourably than, for example, China, which is reported to have been negotiating arms sales to the previous regime as recently as July. But until a new government is established, the terms for accessing Libyan hydrocarbons in the future will remain unclear. For the moment, it appears that a government oil minister will set policy and the new NOC head, who has stated that existing contracts will be honored for a while at least, will continue to oversee operations until a new government is elected.

There is, among some, a perception that Libya is now a mature oil-producing region, as most of the major discoveries were made during the 1960s, and discoveries have been getting smaller. However, despite the fact that Libya has the largest proven oil reserves in Africa, most analysts agree that the country is still underexplored. There is also possibly major gas potential in Silurian shales in the south, as yet unexplored. Despite the uncertainties and potential dangers of a precarious peace, many oil companies will find Libya too attractive not to consider. In the not too distant future, if a more efficient and decent system of government is safely established, Libya’s young population may soon be among the most prosperous in the world.