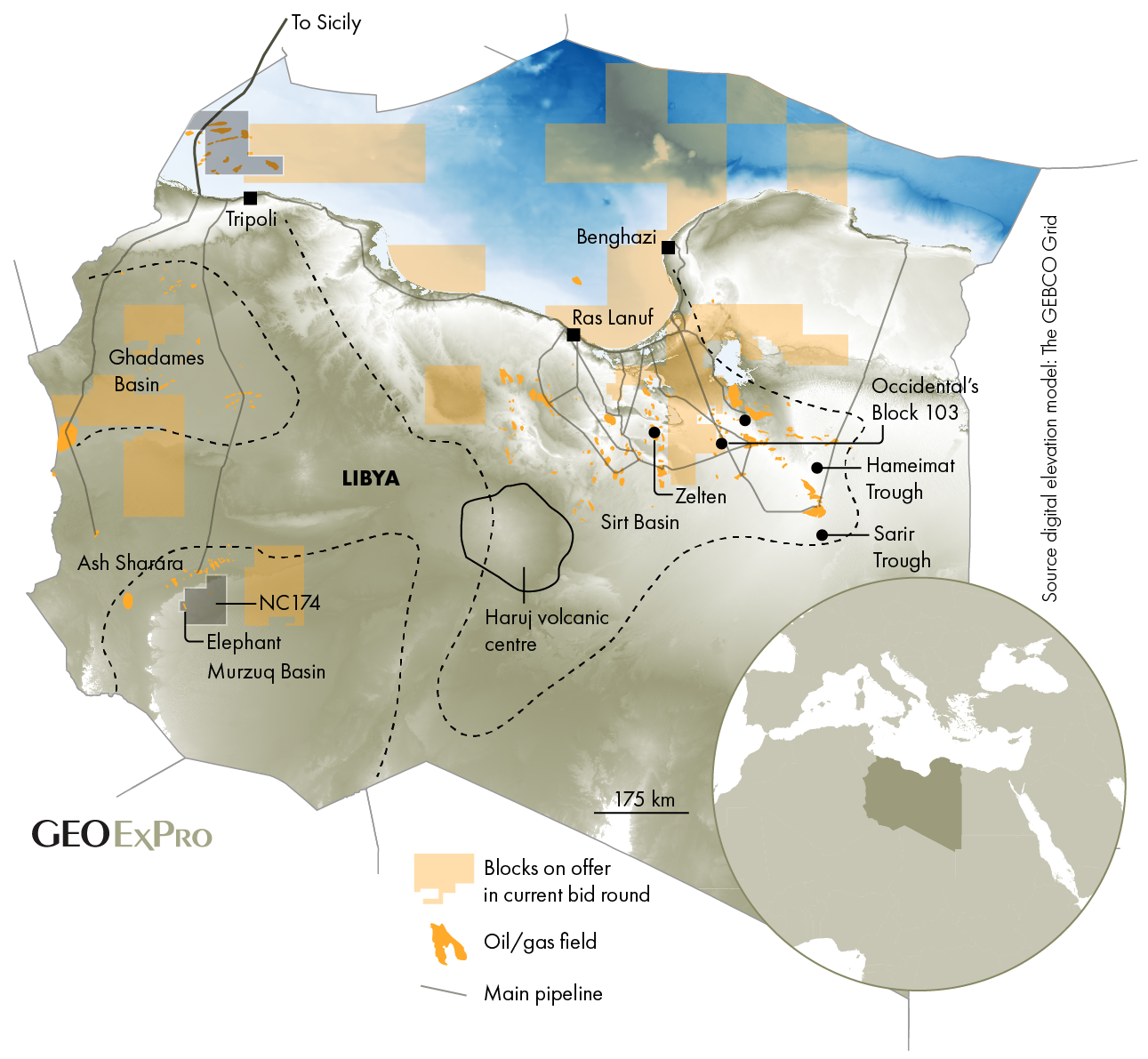

In his book “The prize”, Daniel Yergin describes how Libya’s entry on the global oil stage in the 1950s was spectacular and engineered wisely. Yergin quotes the Libyan petroleum minister: “I didn’t want my country to be in the hands of one oil company.” Rather than giving out large concessions to only a few companies, he awarded smaller blocks to a range of operators.

It took a bit of time for the first discovery to be made, and bp was already clearing its warehouse when Standard Oil of New Jersey made the first strike at Zelten in 1959. This led to the discovery of another ten fields during the next two years.

One company in particular deserves a special mention here, before we move on to the main topic of this article. It was in 1966 when Occidental struck oil in Block 103. Testing at an incredible rate of 75,000 barrels per day, this discovery is interesting because it was found at the site of a former Mobil camp. It was the use of seismic data that had allowed the identification of the prospect, beautifully illustrating how technology enabled the finding of previously unidentified resources.

This article is not about Libya’s initial oil exploration boom in the 1950s and 1960s. Much has been written about that already. Instead, we take a look at more “recent” developments, which are worth knowing more about, given the country’s current efforts to revitalise exploration.

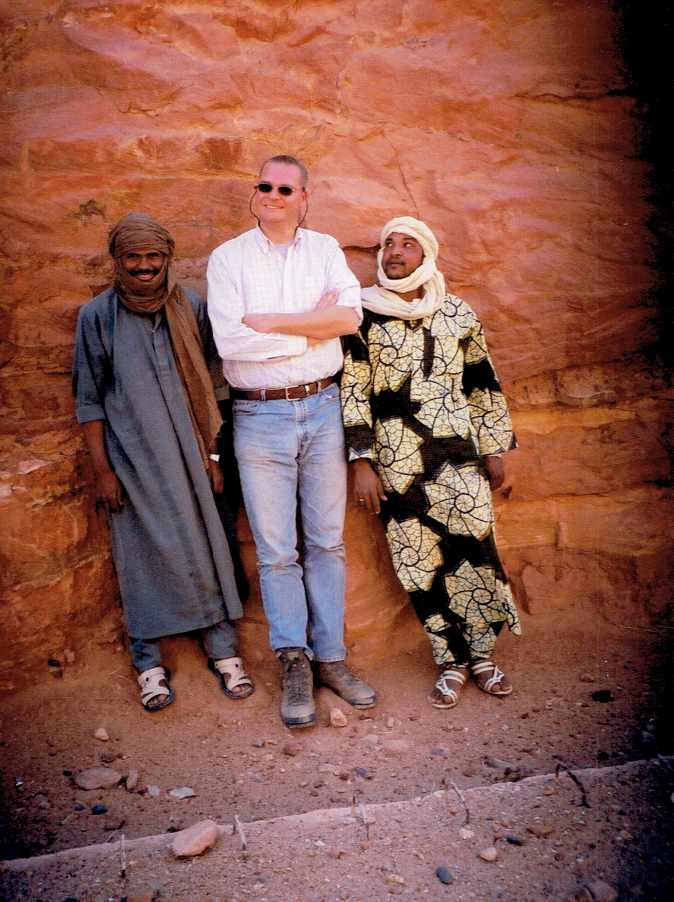

I talked to three people who were there during those years: Bashir Elmejrab worked for Lasmo and Shell at the time, Bas van der Es explored with a Wintershall team, and Henry Williams spent a few years in Libya for Suncor. All three share some of their experiences. As such, this article is not an exhaustive overview of events, but rather sheds some interesting insights and thoughts on the exploration landscape at the time, told by people who were there, on the ground.

New hopes

Bas van der Es spent five years in Libya from 2001 to 2005. During those years, he witnessed the first part of the EPSA 4 licensing round, which consisted of four different stages. It was initiated by a government keen to welcome back new international investment in the country.

Whilst exploration and development activity had not ceased completely in the decades before, the (partial) nationalisation of oil and gas assets by Mu’ammar Ghadafi in 1972-73 did herald a long phase of reduced activity from an international operator perspective.

“You can imagine that there were high expectations as soon as the EPSA 4 (Exploration and Production Sharing Agreement) rounds were announced in 2004,” says Bas. “Many of the major international companies were there, and they were all bidding against each other.”

Woodside was one of the big and unexpected winners at the time, probably helped by a key person from the Australian company who was rumoured to have good connections. “However,” says Bas, “Woodside’s Libya adventure did not go entirely to plan. I believe they drilled about 10 dry or sub-commercial wells in a period of only two years and then left. Quick entry, play hard, and quick exit.”

In turn, Exxon played the bidding game in an interesting way.

They had taken a detailed look at everything, both onshore as well as offshore, but only went for offshore acreage in the end. “We thought they offered a lot of money for it,” recalls Bas. “However, with the 2011 uprising, I realised it was a safer investment than onshore.”

The work programs of the newly awarded licences were quite extensive, which means that there was a fair bit of drilling taking place between 2005 and 2011. “But, at the end of the day, discoveries were either small or lacking altogether,” says Bas. “In my view,” he continues, “the geologists working in Libya in the 1960s and 1970s were all quite well aware of where the main plays started and ended. Therefore, the existing licences were already situated in the best areas. Once drilling was done outside these main fairways, exploration success collapsed.”

This observation of the quality of work done by the earlier generation of explorers is backed up by Henry Williams, who worked for Suncor in Libya during the years before the country’s power struggle. “In the mid sixties, when Mobil was still in Libya, they must have had a team of excellent geoscientists,” Henry said. “We often referred to their earlier work, which, even after 30 years, was a valuable source of data and interpretations.”

Yet, there was room for discoveries to be made. “We drilled a string of successful wells in those years,” says Bas, “which may have actually fuelled some of the expectation that companies had for the EPSA 4 rounds. Based on a new concept, which relied on successful trapping in hanging wall closures next to basement highs, the company found a series of fields in concessions NC97 and NC98, each of them in the order of 100 to 200 million barrels in size.

Three times unlucky

The history of Shell in Libya is a fascinating account of how companies perform exploration in the same country over multiple decades, under different circumstances and driven by different leadership teams. Here, the story is told by Bashir Elmejrab, who currently teaches petroleum geology and seismic processing and interpretation at the University of Tripoli. In 2017, he retired from Shell after spending two long periods with the major in Libya.

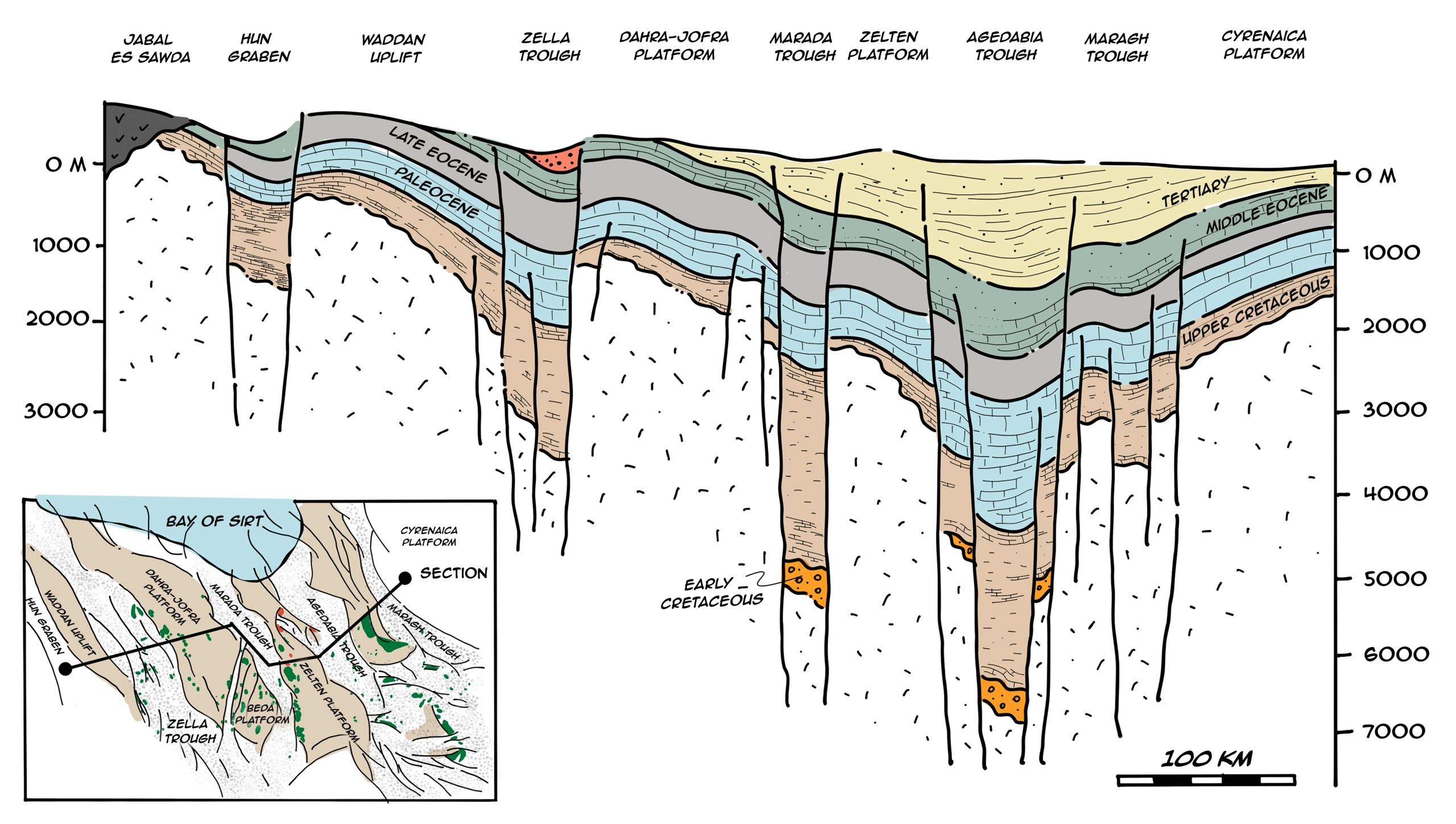

“After graduating in 1981, I joined Shell’s Libya team as a junior seismologist, working on the Sirt Basin,” Bashir says. “This basin has always been the most important oil and gas province in Libya.”

Within the Sirt Basin, which accounts for 80 % of Libya’s reserves, most hydrocarbons are found in Tertiary carbonate reservoirs deposited on intra-basinal horst blocks and platform edges. About another quarter of the discovered volumes are trapped in the Lower Cretaceous – Nubian / Sarir play. This play has been extensively and successfully explored in the south-eastern sub-basins, within the Hameimat and Sarir Troughs. The deeper troughs of the central Sirt Basin, however, are still an underexplored domain in this mature hydrocarbon province.

In the 1980s, during the second EPSA round, Shell was interested in exploring the flanks of those basins more,” Bashir says. However, the company was not very successful; it drilled four unsuccessful wells, three in the Sirt basin and one in the Ghadames Basin.

The 1980s round of drilling can be seen as the second phase of exploration by Shell to prove additional volumes in Libya. In the 1960s and early 1970s, before they left the country temporarily, the company already had licences in the northern and central part of the Sirt Basin. “It resulted in one big discovery in the northeastern corner of Sirt Basin, in a very tight Eocene carbonates,” says Bashir. “This discovery is still undeveloped, though.” In the same period, Shell also explored the Ghadames Basin in the west of the country, but only found gas. “Unfortunately, there was no appetite for gas at the time,” adds Bashir.

In May 2005, Shell returned to Libya for the third time and secured a large acreage position in the northern and central part of Sirt Basin, with favourable EPSA 3 terms. It was the same areas they had explored twice before. However, a large tract (approximately 19,000 km2) of newly processed seismic data had improved imaging significantly, providing more confidence in mapping deeper parts of the basin. Further helped by gravimagnetic surveys, which suggested that there was some structuration, it was decided to go deeper than the basin flanks this time and explore the grabens instead.

“The company applied for some big blocks, as Shell did in those years,” says Bashir, who had returned to Shell as an exploration geologist in 2005 following a long international posting with another explorer and a stint with the NOC.

“We were clearly going for the deep plays, aiming to find large gas volumes,” he says, “including the Nubian sandstone that was found prospective further to the southeast in the Sirt Basin, where bp had made some big finds in the 1960s. However, there were no wells in the deeper parts of the basin in Shell’s concessions at the time.

Another thing that had changed was the increased appetite for gas in the early 2000s. Whilst oil had always been the main target, in those years Libya had realised that gas could be an important export product as well, especially now that Europe proved to be an eager customer in the light of declining domestic production. As such, there were big plans to expand the already existing LNG plant that Exxon built in the 1970s. But first, this gas needed to be found.

In the end, Shell drilled five exploration wells, with the first being a deep HPHT well ( 20,300 ft – deepest well in Sirt basin) and four shallower wells.

When the first deep well reached 20,000 ft, overcoming many technical problems, the primary target, the Nubian sandstone, turned out to be water-wet and of poor reservoir quality. The second well also targeted the Nubian Sandstone, but it proved to be absent. Instead, a small gas column was tested in a shallower Eocene carbonate reservoir. Gas was encountered in the third well, but unfortunately, a sudden and unexpected overpressure event led to a well shut-in, resulting in costly well control remedial operations and a final abandonment. The fourth well proved gas again, but in tight Paleocene carbonate reservoirs, and testing operations failed on the second attempt. In early 2011, while the fifth well was progressing, operations were suddenly halted when the uprising against the Gaddafi regime had started in Benghazi, spreading fast towards Tripoli.

By mid-February 2011, Shell and other IOCs commenced the evacuation of the expat staff from Libya. “Shell used the force majeure to leave the country,” says Bas, “and the exit was not entirely against their desire, probably.”

Wishfull thinking

“You don’t discover gas by just dreaming about discovering gas,” adds Bashir, “but that is what seemed to have happened in those years. There was something wrong with the expectations.”

Shell was aiming to be a major gas networking leader in a strategic geographic area, but this was all dependent on exploration success in a harsh and hazardous subsurface environment. “The hopes were dashed soon after drilling the first and second wells, which were anticipated to tap into substantial gas volumes,” says Bashir. Until the results came in.

Altogether, Shell has never been lucky in Libya. Was going back to the same basin twice a smart move? As the technology had progressed, every time the company came back, and with that the focus onto other parts of the basins, it is too easy to say that it wasn’t smart to do so. But especially during the third exploration phase, it was the expectation pre-drill that had a detrimental effect on how the poor drilling outcomes were perceived.

Murzuq basin

The Murzuq Basin in the southwest of Libya may not be the most important source of oil in the country, but it does host a number of particularly big finds that were made not too long ago.

The first one of those is the Ash Shararah discovery, made by Rompetrol from Romania in 1985. “Rompetrol didn’t have the required funds to progress the development of the giant discovery with the NOC, also due to imposed sanctions,” says Bashir. “However, a deal with the Prime Minister of Spain turned Repsol into the new operator of the field, and soon after, its development went ahead. It was then realised that the field contained much more oil than Rompetrol had claimed, reaching more than a billion barrels in recoverable resources.”

A few years later, during the second half of the nineties, UK-based company Lasmo became the main player in yet another big discovery (Elephant field, approximately 1.4 billion barrels OIIP) in the Murzuq Basin. By that time, Bashir had joined the company following his first stint with Shell.

“Before we made the Elephant discovery,” Bashir says, “we drilled three wells in block NC174 with Lasmo, partnered with a consortium of Korean companies under the name of Pedco, before Eni joined. One of these wells was a discovery, another a minor find and one was a failure. All in all, this caused the company to be in choppy financial waters, and talks started to sell the company. However, it was chief geologist Jonathan Craig who managed to convince management to drill the Elephant prospect before giving up.”

That took quite a bit of effort, though, because another company under the name BrasPetro had just drilled nine wells in the area that all failed. And one of those wells was very similar to the Elephant prospect; it had a large reverse throw, with a similar Ordovician glacio-marine sandstone target.

However, the Elephant trap was giant, and ultimately, management was convinced to get it drilled. And so it did, with a major discovery as a result. “It was a big event, and it was mentioned in a lot of newspapers in 1997,” says Bashir, who emphasises that the name Elephant was not because of the size of the discovery, but rather because of large elephant rock engravings in the area.

“Charge was the critical risk for Elephant,” explains Bashir. “We had no clear idea from which direction it came, which had a detrimental effect on our probability of success. But they took the risk.”

A CORE STORE IN A WAR ZONE

If reports are correct, a big core store in Libya became the victim of the 2011 power conflict. Being located in Ras Lanuf, which became a hotspot of fighting, it was apparently damaged by bombings.

Henry Williams made several visits to the Ras Lanuf core thanks to the cooperation of Harouge management and geologists before it was damaged. He remembers it hosted numerous exploration and development cores from the Sirt Basin, ranging from the 1960s to the present day. “It was a big warehouse, and because it had no air conditioning, we normally went there in November,” he says.

“The boxes were stacked on high shelving,” he describes, “and because there was no forklift, it was almost impossible to get your cores down when they were at the top of the pile, especially if they were not slabbed. Also, many boxes did not have lids on them, meaning that over time, sand would have blown into them and needed a good dusting before core examination. I did, however, find the visits provided invaluable insight into understanding the depositional environment and diagenetic reservoir development of many diverse clastic and carbonate reservoirs. One core included a granite basement overlain by talus debris with granite blocks up to a metre in diameter interbedded with fluvial sediments. You could never have interpreted that correctly based on wireline logs!”

What about the current exploration outlook?

Earlier this year, a new bid round was announced by the Libyan NOC, underscored by an international road trip to promote the available acreage.

I spoke to an exploration manager from a company that is currently active in the country. “I don’t know how successful it will be,” he said. “A lot of companies are worried about the fiscal terms, even though they are supposed to be better now. Contractually, the country can also be quite tough. However, near-field exploration potential is surely there,” he added. “Also, some big fields are just sitting at a 10 % recovery factor, so imagine the potential for enhanced recovery. Hence, there is a lot to be gained from existing fields, even before you would consider exploration.”

Bashir is not very upbeat about the country’s exploration prospects either. “Our challenge is that we have two governments,” he says, “one in the east and the other in the west, and that is not the ingredient for a stable country. Exploration was almost always done by the international partners, but I fear that these companies will not be coming back to Libya soon. It is just not stable enough.”

Taking all this in, it is clear that exploration efforts during the years prior to the 2011 uprising had mixed results at best, especially onshore, where the established plays have been mapped out well. To me, listening to what I heard during the conversations I had, it may be the (re)development of existing discoveries and fields that has the most potential in Libya, with recovery factors lagging behind from what should be achievable these days. However, that doesn’t mean that there is no potential for exploration at all, as someone reiterated: “Libya is where the North Sea was a few decades ago.” Whether these resources will be proven tomorrow is another matter.

EXPLORATION AND VOLCANICS

An interesting exploration story from Libya comes from near the large Haruj volcanic centre in the Sirt Basin. It is mostly Pleistocene in age and reaches up to 1,200 m above sea level. “Some of the lava flows extend close to producing oil fields and could potentially be hiding other undiscovered hydrocarbon deposits,” Henry Williams says. However, CO2 might be a risk there. “A few wells drilled some distance from the volcanic outcrops encountered CO2 rather than oil in prospective reservoirs,” he says. Based on Henry’s subsequent experience in Canadian helium exploration and production, he considers that this may have been caused by secondary flushing during Haruj magmatic activity.