When the Laki Fissure opened on June 8, 1783, the hot, rising magma mixed with groundwater and turned almost instantly to steam, causing explosions of water, ash, gases and volcanic bombs. Over the next eight months 130 craters appeared and, although it was less explosive, the lava continued to flow, filling a gorge nearly 400m deep and covering an area of 565 km2. About 90% of this magma erupted in the first five months, half of it appearing in the 48 days after the first explosion, flowing as quickly as 15–17 km/day, fast for a basaltic lava flow.

By the time the eruptions had finished in February 1784, about 15 km3 of magma had been extruded, making it what is believed to be the most prolific eruption recorded in historical times, although there are many events to rival it in geological history.

Major Consequences.

It is estimated that a fifth of the population of Iceland – 10,000 men, women and children – died as a result of these eruptions, along with 82% of the country’s sheep, 53% of its cattle and 77% of its horses. Some people were caught up by the lava flow, or were killed by ash falls or superheated gas pouring from the craters, but the majority of the deaths were a consequence of the vast quantities of toxic gases which were thrown many kilometres into the air. These contained an estimated 8 million tons of hydrogen fluoride and 120 million tons of sulfur dioxide, killing and poisoning vegetation and leading to a three-year famine in Iceland.

Map of Iceland showing the location of the Lakagigar volcanic fissure. (Source: NASA/Bruce Winslade)But the effects were felt far beyond Iceland. These huge ash clouds and their associated ‘acid’ rain blanketed first Europe in a thick haze, and then spread via the jet stream across the whole northern hemisphere; by early July they had reportedly reached China. The summer of 1783 in Europe was noted as unpleasantly hot (as it was in Iceland, where malaria broke out) and possibly as many as 23,000 people died in Britain from inhaling sulfur dioxide. This was followed by a very cold winter throughout Europe, with severe flooding resulting from the eventual thaw, and this cycle of extreme weather conditions continued for several years, causing crop failures, poverty and famine. It is suggested that repercussions from the climatic vagaries caused by Laki may even have helped trigger the French Revolution and other social upheavals in the late 18th century.

Map of Iceland showing the location of the Lakagigar volcanic fissure. (Source: NASA/Bruce Winslade)But the effects were felt far beyond Iceland. These huge ash clouds and their associated ‘acid’ rain blanketed first Europe in a thick haze, and then spread via the jet stream across the whole northern hemisphere; by early July they had reportedly reached China. The summer of 1783 in Europe was noted as unpleasantly hot (as it was in Iceland, where malaria broke out) and possibly as many as 23,000 people died in Britain from inhaling sulfur dioxide. This was followed by a very cold winter throughout Europe, with severe flooding resulting from the eventual thaw, and this cycle of extreme weather conditions continued for several years, causing crop failures, poverty and famine. It is suggested that repercussions from the climatic vagaries caused by Laki may even have helped trigger the French Revolution and other social upheavals in the late 18th century.

And the consequences were felt even further afield, with North America experiencing exceptional cold in 1784, when even the Mississippi froze in New Orleans. The raised temperatures of the sea relative to the land caused the monsoons to weaken in Asia and Africa. Possibly a million people died of famine in Japan, while a sixth of Egypt’s population succumbed to famine or plague when the Nile did not flood fully in 1784.

A Visit to Lakagigar

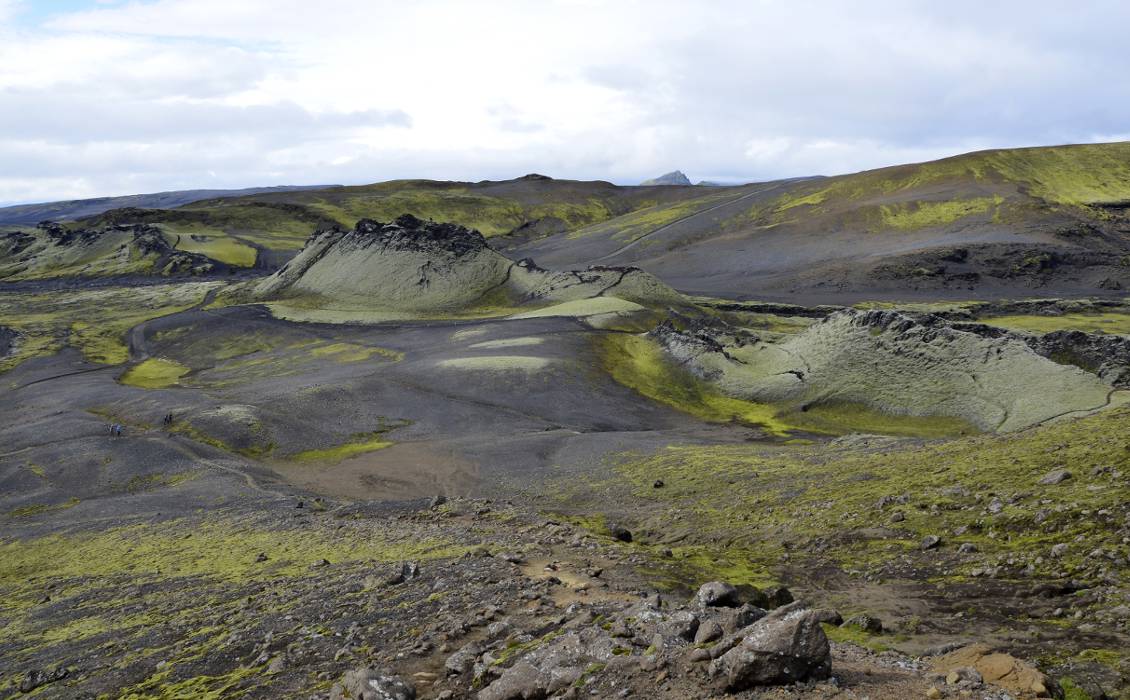

Despite its violent history and the catastrophic consequences, Lakagigar is now a peaceful though slightly eerie landscape of black lava and fuzzy green Icelandic moss. It is a fragile environment, extremely sensitive to intrusion, and is protected as part of the Vatnajökul National Park.

Our photo competition winner Miguel and his wife were lucky enough to visit this amazing location during their trip to Iceland and have shared with us their impressions of traveling around Lakagigar.

Fagrifoss waterfall drops 20m into the canyon below. (Source: )“Our first stop is Fagrifoss, a waterfall that drops 20m into a canyon. Seen from above, it seems as though the walls are about to collapse and although there is a cord designed to prevent you from approaching the cliff (quite unusual in Iceland, where they usually prefer free access), everyone goes to the edge to look at the drop.

Fagrifoss waterfall drops 20m into the canyon below. (Source: )“Our first stop is Fagrifoss, a waterfall that drops 20m into a canyon. Seen from above, it seems as though the walls are about to collapse and although there is a cord designed to prevent you from approaching the cliff (quite unusual in Iceland, where they usually prefer free access), everyone goes to the edge to look at the drop.

“The scenery is breathtaking – and this is just the start of the route!

“Although there is no sunshine, at least it does not rain, and the clouds give an even more dramatic look to the landscape, which is composed of black sand, rock formations and striking moss so green that it almost hurts your eyes.

“The track is slow, and needs a 4X4, with many stones, potholes, hills and streams – but worth it, not only for what awaits us at the end, but as part of the experience itself. We reach the edge of Eldhraun, the lava field that extends from Lakagigar, keeping to the black ash path. All around us is a beautiful carpet of green and squishy moss, with small islands of black ash.

“Eventually, we arrive at the foot of Laki volcano. We park the car in the specified area and climb the steep slope. It’s hard work but the views from the top are well worth the effort: a long line of craters, getting smaller and smaller, stretching to the horizon. We can see small trails surrounding the nearby craters with tiny figures walking on them. One can appreciate from here the vast size of the lava field and it is easy to imagine the destruction that resulted from the eruption.

“We return to the car and drive to the crater of Tjarnargígur, to do a little hiking along an ash trail. The crater walls, floor and everything else are all mossy and we now fully understand how fragile it is, and how easy it is to damage it. We wander among the lava, admiring the surreal environment around us, knowing that nowhere else on Earth can you find such a place.”

Looking to the Future?

The Laki Fissure Eruption is well documented by people who experienced it first hand, from local Pastor Jón Steingrímsson, who kept a diary as the lava threatened to engulf his church, to naturalist Gilbert White in England and Benjamin Franklin in Paris. As a result, it is frequently studied and cited during discussions on the potential repercussions of climate change. Seeing the dramatic effect which the ash fall from the much smaller eruption of Iceland’s Eyjafjallajökull in 2010, it is pertinent to wonder how the modern world would cope with another event like Laki, if – or more correctly, when – it should occur.