Is there a future for OPEC?

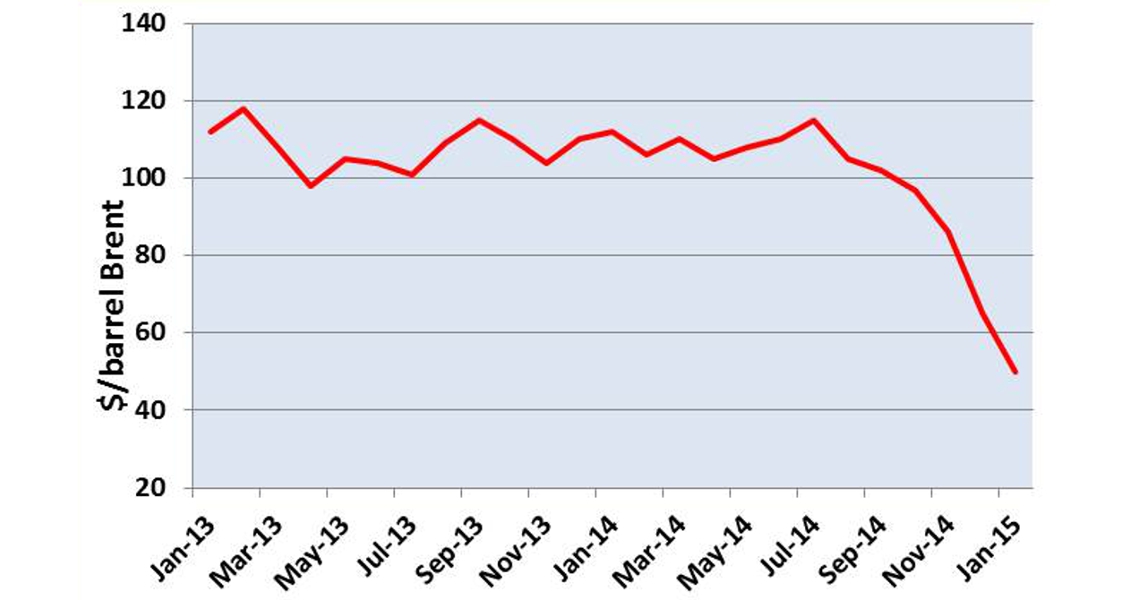

The plummeting oil price was first met with disbelief, but now mounting alarm. In December, when Brent hit $60, Goldman Sachs calculated that over $1 trillion of projects were set for cancellation: that devastation has continued throughout January as Brent has hit new lows. Market ‘bears’ are now betting on contracts that pay out at just $40/b and Western banks are stress-testing at prices of $35/b. Gas and ethane prices are tumbling.

What has happened to our usual saviours, the Saudis?

As the world’s one and only swing producer – apparently able to raise and lower production at will and calm markets with a word – Saudi Arabia has long been relied upon to keep supply and demand in balance. But at the November 2014 conference, after eight months of rising world inventories, Saudi Arabia’s oil minister announced that the rules have changed. The Kingdom (KSA) is relinquishing its swing producer status and OPEC as a whole will continue production at 30 MMbpd. OPEC will not cut production even if Brent hits $20/b.

Conspiracy theories

On the surface, nothing quite makes sense here – hence the plethora of conspiracy theories. Is Saudi aiming to wipe out funding for ISIL? Or decimate the Russian and/or Iranian economies? (If so, is it at the behest of the US?) Or is this an attack on US and Canadian production? By regaining ‘market share’ Saudi would resume its position as number one supplier to the world, and crucially to the US.

If any of the above are true, they are imprecise policies that come with considerable collateral damage – to the Kingdom itself, its allies in the Gulf and to other OPEC states. Saudi Arabia’s projected budget deficit for 2015 is a sizeable $39 billion – affordable, but definitely painful. Of the eleven other OPEC members, Venezuela is already in deep crisis and Nigeria’s naira is at a record low. It is hard to see how Ecuador, Angola, Algeria and Iran will bear prolonged low prices. OPEC has never been noted for its cohesion, but this looks like a killer. Will the organisation itself survive?

Loss of control?

Here’s another theory. For years the extent – and state – of Saudi’s reserves have been shrouded in secrecy, and it has long been speculated that the Kingdom no longer has the ability to lift production at will. Indeed, the release of Wikileaks emails in 2010 revealed that the US administration expected KSA to lose control of upward prices as early as 2012.

What better time to officially announce the abandonment of the role than when prices are on their way down?

Saudi Arabia, of course, blames low prices on the lack of discipline among non-OPEC producers. This is new territory. The current glut is not the result of an exterior shock – there’s no new banking crisis – the problems now come from within the oil market itself. According to Saudi Arabia’s oil minister, Ali al-Naimi, the issue is efficiency. The $100-plus oil price – fed by the super-cycle of the last ten years and a flood of speculative capital into commodity markets – has allowed investment in inefficient production while at the same time high energy prices have helped depress economies and flatten demand growth. This supply glut and weak demand has sent prices downward and Saudi Arabia argues that it is the high-cost producers who should be squeezed and, where necessary, go to the wall.

So the Kingdom is characterising its inaction as a deliberate and positive act to regain market share. Still, doubts remain. Does the current crisis signal that KSA has lost its ability to operate as swing producer? For years Saudi Arabia has occupied such a bizarre, haloed position in the oil world, based on almost no real information. Markets have needed to believe in the Kingdom’s ability to control prices – at times it has felt remarkably as if the Emperor might be wearing no clothes….

Two questions loom. First, once the industry has ‘shaken down’ and production has slowed, is there a role for OPEC? OPEC has always been a shaky cartel, renowned for its in-fighting and quota cheating. That will only be exacerbated by a prolonged price down-turn. Poorer members will be hard pushed to keep up revenues, even if they breach quotas and work their fields to the maximum. Maybe in a slimmed down world, when they have regained market share, the group will appear more cohesive – the alternatives are to hang together or to hang separately – but without price controlling powers, OPEC will have no relevance.

So, the second question: can/will Saudi Arabia resurrect its swing producer status? If it does not, we can assume the theory is correct – Saudi Arabia’s reserves are less than currently admitted, and they have been severely damaged by over–production. The dream time of Saudi control may be over.

Abandoned to the market

We are then left completely to the market – which means a new world of extreme volatility. There will be no soothing words from the Saudi oil minister as prices peak or trough, and production will be even more concentrated in the world’s hot spots. We’ve already had our introduction: the market has just taken us from over $110/b to $50 with hardly any actual change in demand or supply. Now, imagine one major supply disruption – take your pick….

Spikes of $200 might not be far away. It seems the job of making long-term investment decisions may have just got a whole lot harder.

Nikki Jones

Bristol

January, 2015.

To learn more about the history of OPEC, read GeoExpro article, ‘The Road to OPEC 1960’