In April 2009, the Iraqi Oil Minister Hussain Al-Shahristani announced in a press conference in Paris that he expected the international oil companies to invest $50 billion in Iraq’s oil industry over the next five years. Finance and geopolitics are not, however, the only factors in the development of Iraq’s petroleum. Geoscience and technology will play a significant role in assessing and developing these resources.

“Tectonics Rules”

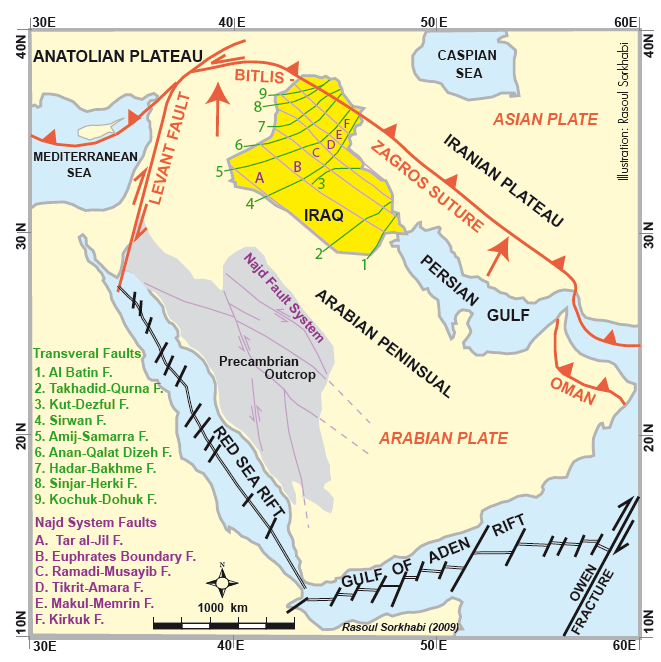

Iraq’s geology is largely a product of three tectonic phases or regimes: the Arabian craton; the Tethys ocean; the Zagros-Bitlis orogeny. Iraq is part of the Arabian plate, a Precambrian shield consolidated and deformed during the so-called “Pan African” orogeny” (700-550 Ma). Throughout the Paleozoic and Mesozoic, sediments of the Tethyan oceans (the Cambrian-Carboniferous Proto-Tethys, the Ordovician-Jurassic Paleo-Tethys and the Permian-Eocene Neo-Tethys) were deposited on the passive margin of the Arabian craton deepening toward Paleo-Asia. Tethys was not a single ocean but a series of at least three major oceans which opened and closed successively as continental fragments were separated from Gondwana margin and accreted to Asia. This long and thick sedimentary record was controlled by both sea-level changes (in response global climate changes) and tectonic events, mainly the extensional opening and collisional closing of the Tethyan oceans. Finally, as Neo-Tethys was subducted beneath the Iranian and Anatolian margins of the Asian plate, the Arabian continental collision produced the Zagros Mountains in southwest Iran and the Bitlis-Poturge Mountains in southeastern Turkey.

Except for the Kurdistan region in NE Iraq, where parts of the Zagros orogen outcrop, the rest of Iraq is essentially covered with young sediments; therefore, the subsurface geology needs to be deciphered from the other methods of investigation. In some areas, drilling of oil wells has supplied much information about the stratigraphy and facies distribution, but to map the entire country data from satellite images and geophysical (seismic, magnetic and gravity) surveys are crucial. Using a variety of data, Tibor Buday (a Czech geologist) and Saad Jassim (an Iraqi geologist) have worked out a country-scale tectonic map of Iraq. These authors note that the Precambrian basement of Iraq is crisscrossed by major lineaments. Some of these lineaments striking NW-SE are on par with the Najd fault system of Saudi Arabia, and as such, they probably formed as left-lateral transtensional structures during the latest Proterozoic. A second category of lineaments striking W-NE are transversal structures, possibly also formed in the Precambrian, but have been reactivated during the Cenozoic, some with left-lateral movements. These transversal structures are significant because they often dismember the NW-SE trending “whaleback” anticlines into domal structures.

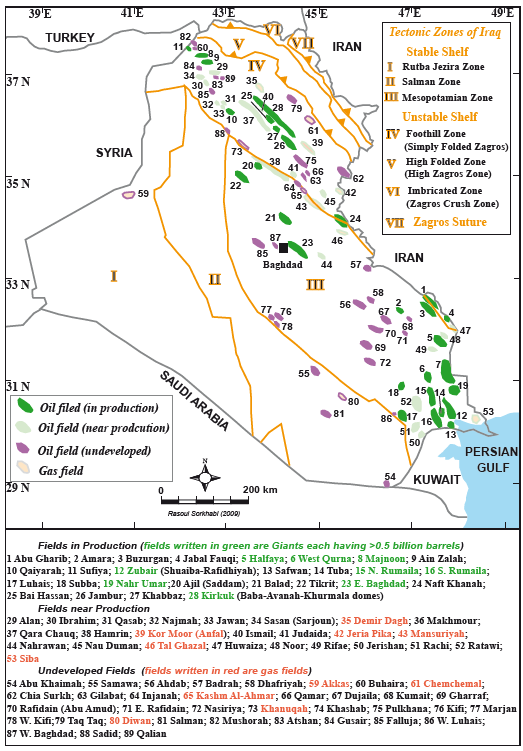

Iraq is broadly divided into three geologic divisions: the Stable shelf, the Unstable shelf, and the Zagros Suture. The word “shelf” here refers to the Tethys continental shelf of the passive Arabian margin. The Stable Shelf is relatively less deformed than the Unstable Shelf during the Zagros collisional tectonics.

The Stable Shelf, located in western and southern Iraq, may be divided into three zones: (1A) The Rubta-Jezira zone is essentially a Paleozoic basin that became an upthrown block during the Late Permian opening of Neo-Tethys. (1B) The Salman Zone, the eastern extension of the Rubta-Jezira zone, is a gravity-magnetic high (shallow basement) possibly formed during latest Proterozoic and was reactivated in the Late Permian. (1C) The Mesopotamian Zone, which is drained by the Tigris and Euphrates rivers, is a Cenozoic foreland basin of the Zagros orogen superimposed on the Tethys shelf sediments. Here Paleozoic, Mesozoic and Cenozoic sediments are fully developed to a thickness of 8-13 km, thickening to the east. The western boundary of the Mesopotamian zone is a basement high, probably formed in the Late Permian.

The Unstable Shelf, located to the northeast of Iraq, is divided into two zones: (2A) The Foothill Zone is structurally an extension of the Simply Folded Zagros Zone in southwest Iran, and is stratigraphically similar to the Mesopotamian Zone. It contains numerous anticlines and a Phanerozoic sedimentary succession of up to 13 km. (2B) The High Folded Zone, an extension of the High Zagros Zone, is a 25-50 km wide deformed zone uplifted during the Cenozoic collision. This zone contains thrust-bounded elongated fold structures with Paleogene carbonates in their cores and Neogene clastics on their flanks. It is in tectonic contact with the Zagros Suture Zone.

Petroleum Plays and Fields

While Iraq is often included in the Greater Arabian or Zagros basins, the country’s petroleum plays and fields are constrained by the tectonostratigraphy of its various zones or “sub-basins.” Therefore, geologic information from these tectonstratigraphic zones offers a first-order framework for assessing Iraq’s petroleum plays.

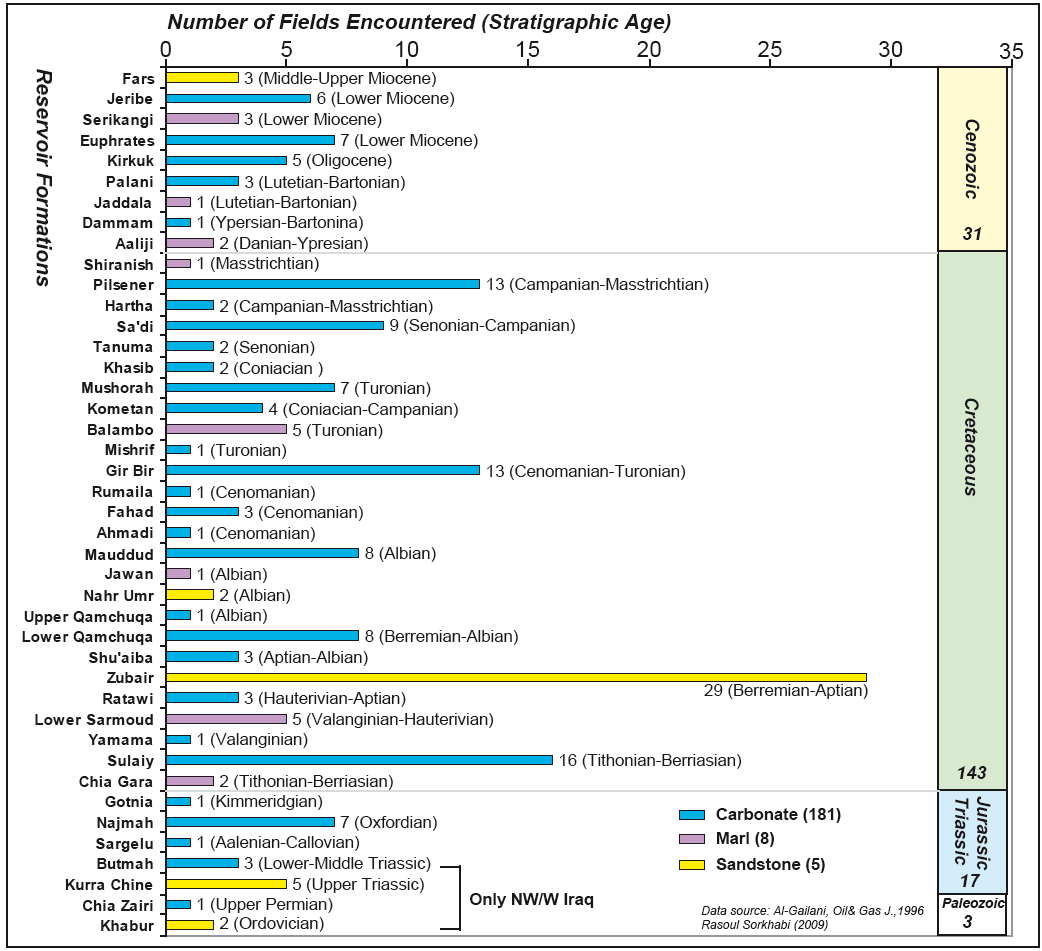

The Paleozoic-Triassic plays seem to be widely present in Iraq although with varying characteristics and qualities. In the High Folded zone, Paleozoic-Triassic sediments are structurally complex. In the Foothill and Mesopotamian zones, these sediments are deeply buried (>5 km), and therefore, low-permeability reservoirs and non-associated, basin-centered gas accumulations may be expected. In the Rutba-Jezira and Salman zones of the Stable Shelf, which largely correspond with the Western and Southern Deserts of Iraq, exploration of relatively shallow Paleozoic oil and gas payzones should be promising and without major geological complexities although our knowledge of the subsurface in these areas remains poor. The Mesozoic-Cenozoic overburden in these parts of the Stable Shelf is not very thick; however, temperature gradients are the highest in the entire Iraq (25-35°C per kilometer) favoring thermal maturity of source rocks. Indeed the discovery of oil and gas in the Silurian clastics of the Akkas field in western Iraq in 1993 provides an important correlation with the Silurian (Qusaiba) “hotshale” of central Saudi Arabia, some 2000 km further south. This Iraqi oil is of high quality (48 API, 0.01% sulfur) and the associated source rock has a total organic content of 16%. In 2007 high flow rates of oil were reported from a test well in the Akkas field.

Currently, Iraq’s petroleum fields are concentrated in the northern Foothill and the southern Mesopotamian zones. Within these zones, five petroleum plays have been recognized:

- Jurassic carbonates (relatively minor but promising as drilling moves deeper);

- Cretaceous carbonates (various reservoir units already constitute a major play);

- Zubair clastics of Lower Cretaceous (encountered in many fields);

- Paleogene carbonates (relatively a minor play); and

- Oligocene-Miocene carbonates (a major play and the first one to be discovered).

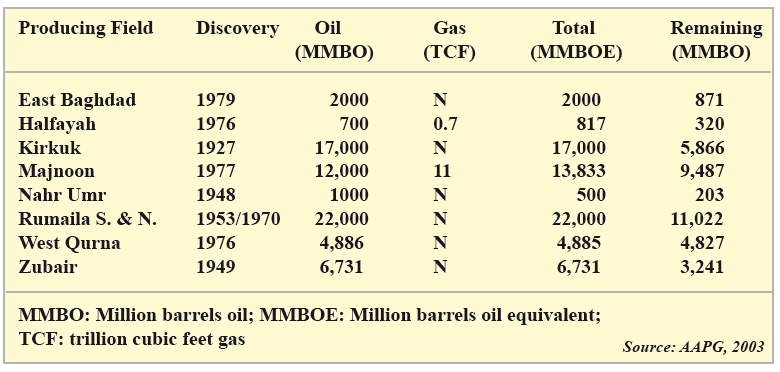

Iraqi geologists have identified 526 prospects (Geotimes, October 2003) but the majority of them are undrilled or have not been appraised; 9 fields are considered to be super-giants (each having >5 billion barrels) and 22 fields as giants (each >500 million barrels). If the past discoveries are a yardstick, Iraq’s undeveloped fields are largely carbonates. Of about 90 discovered fields, the majority are undeveloped, partly developed and thus yet to come on stream. Historically, Iraq’s oil production has come virtually from a few large fields, notably Kirkuk, Rumaila, Zubair, and Bai Hasan.

Data from the producing or appraised Iraqi fields indicate that about half of them are oil and gas fields; the gas being associated gas or gas caps. About a quarter are light crude (22-48 API gravity), and some 15% are essentially heavy oil (<20 API values). The main fields with non-associated gas pay zones include Demir Dagh, Chemchemal, Ko Moor, Jeria Pika, Mansuriyah, Khashab, Kashm al-Ahmar, Khanunqah, Tal Ghazal, Siba, Diwan, and Akkas. Of these, only Demir Dagh and Kor Moor are active gas producers.

Reserves, Production, and Future Prospects

Estimation of oil reserves is especially a daunting and highly speculative task in Iraq where secrecy of data, scarcity of independent or modern surveys, as well as disruption of exploration and production during the years of war and sanctions have limited our knowledge of the country’s oil fields and reserves.

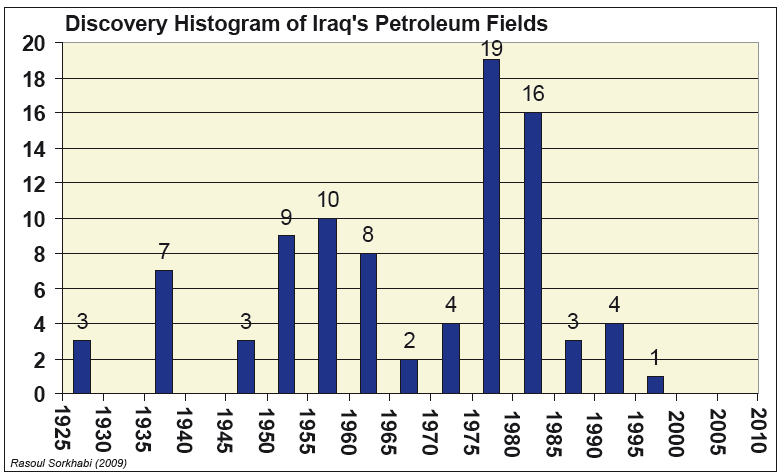

In 1980, Iraq’s oil reserves were estimated as 30 billion barrels; by 1987 they were reported to be 100 billion barrels. In an article, “The End of Cheap Oil,” published in Scientific American (March 1998), Colin Campbell and Jean Laherree argued that this sudden increase in oil reserves in the mid-1980s was not unique to Iraq; it was part of an overall attempt by OPEC members to raise their reserves and production shares. At the 1989 World Petroleum Congress in Washington D.C., Hashim Al-Khirsan and Ahmad Al-Siddiki of the Oil Exploration Company of Iraq placed Iraq’s oil reserves at 100 billion barrels based on 73 fields (35 fields discovered between 1927-1968 by drilling 62 structures, and 38 fields discovered from 1968-1998 by drilling 52 structures). These authors also noted that oil from Cenozoic and Cretaceous reservoirs were about 24 and 76 billion barrels, respectively (with only 100 million barrels from Jurassic-Triassic sediments.)

In a 1996 paper in Oil & Gas Journal (24 June 1996) Muhammad Ibrahim, a London-based consulting geologist, estimated Iraq’s recoverable oil reserves as 33.8 billion barrels (Tertiary), 107.1 billion barrels (Cretaceous), 140 million barrels (Jurassic-Triassic), and 100 million barrels (Paleozoic), totaling 141 billion barrels. Mohammad Al-Gailani of GeoDesign (England) reported Iraq’s “oil-in-place” reserves to be 321 billion barrels. (Oil & Gas Journal, 29 July 1996). In a more recent paper (Oil & Gas Journal, January 2009), Tariq Shafiq of Petrology & Associates (London) estimated Iraq’s total oil resource to be 410 billion barrels, of which 145.5 billion barrels were proved, 22 billion barrels were 15% additional recovery by the modern enhanced methods, 215 billion barrels were potential resources, and 30.5 billion barrels already produced.

Currently, OPEC, British Petroleum and Oil & Gas Journal annual reports place Iraq’s proven oil reserves at 115Bbbl accounting for 9.3% of the world total. These official reports also place Iraq’s natural gas reserves as 111.9Tcf (20Bboe). Al-Gailani (1996) estimated Iraq’s “gas in place” (both associated and free gas) to be 168.4Tcf (30Bboe).

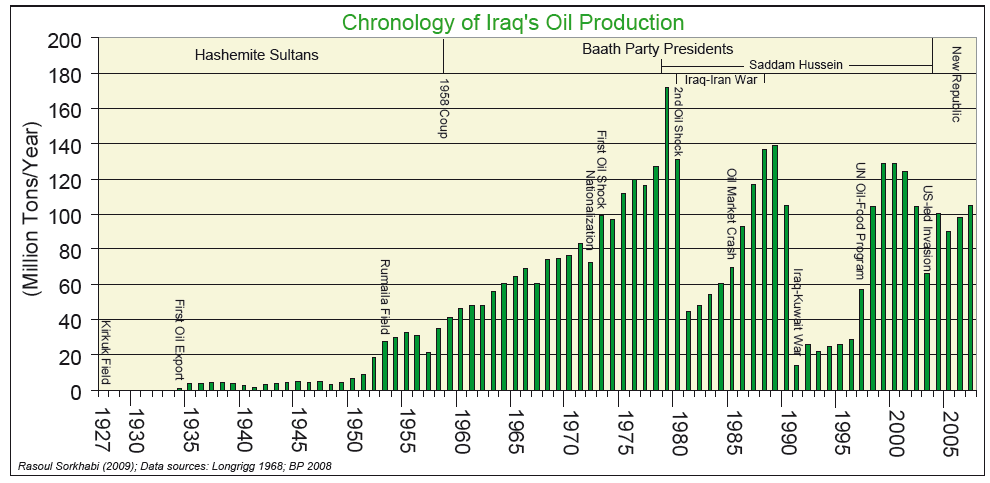

Despite its rich petroleum resources, violent events of the past three decades in Iraq have hampered the country’s exploration and production. Iraq’s maximum production of oil was at about 3.5MMbopd in 1979, a year before President Saddam Hussein started a war with Iran. Iraq has not regained this production capacity yet. Its 2007 oil production averaged 2.14MMbopd.

Why is Iraq Attractive

What makes Iraq attractive for the exploration portfolio of international oil companies are the following factors:

- The country’s location within the Arabian platform and Zagros foreland basin is geologically suitable;

- It has a long and proven record of exploration and production;

- It has low cost reserves in terms of exploration and production;

- Its production capacity yields a high ratio of net export to domestic consumption;

- Infrastructures (pipeline, refineries, export terminals, tank farms) are in place or can be easily reconstructed;

- A pool of well-educated personnel and young workforce exists in the country;

- There are numerous undrilled or undeveloped structures;

- Deeper sections of Iraq’s sedimentary pile are little explored;

- Large mature fields lie in areas with structural compartmentalization; therefore, there are excellent exploration opportunities for smaller marginal fields; and

- Production in most of Iraq’s mature fields has declined; therefore, enhanced recovery techniques and new wells can revitalize these fields without involving exploration costs.

Despite these advantages, as Iraq’s history of oil production shows, political realities on the ground will determine its exploration successes and production capacity in the coming years. If the country moves towards stability, peace, and is united in a vision of reconstruction and democracy, its petroleum resources will form a strong base for economic and social progress. Geoscientists will then be able to paint a more refined picture of Iraq’s geology and petroleum inventory.

Back to the Iraqi Kurdistan

In 2007, the Iraqi Kurdistan Regional government decided on its own to offer exploration blocks to several foreign oil companies. The Calgary-based Heritage Oil Co. now has a story of success to tell. The company, until recently, was led by Michael Gulbenkian, a descendent of Calouste Sarkis Gulbenkian who played a key role in the discovery of Iraq’s firs oil field, Kirkuk, back in 1927 (see “Oil from Babylon to Iraq” in GEO ExPro, No. 2, 2009). Heritage, now merged with Eagle Group (an Iraqi Kurdish concern), obtained a license for the Miran block (1,015 square kilometer, with two structures) in 2007, and completed the drilling of Mira West-1 Well to a depth of 2,935 m in December 2008. This past March, the company announced oil shows of light sweet crude over a 1,100-interval in the Cretaceous carbonates. The Miran block is located to the east of Kirkuk. Several other companies including DNO, Hunt Oil and Niko Resources, are also active in the Iraqi Kurdistan, a region poised to news of oil field discoveries in the coming years.