The terrain along the ultra-slow-spreading Mohns Ridge in the Norwegian Sea is continuously renewing itself with frequent volcanic eruptions across a wide zone in the rift valley, a new doctoral thesis shows. The knowledge is useful, among other things, for companies that want to explore marine mineral deposits.

“Ultra-slow spreading ridges (<15 mm/year) have quite different characteristics than faster (25-150 mm/year) spreading ridges,” says Håvard Hallås Stubseid, researcher at the Center for Deep Sea Research at the University of Bergen (UiB).

He explains that the most obvious difference is the topography. Slow spreading is the key to forming a rift valley along the plate boundary. “Along a fast-spreading ridge, the volumes of magma that flow up from the depths are significant so that a thick volcanic crust is built. At lower spreading speeds, the spreading is less magmatic, and more tectonically influenced,” he explains.

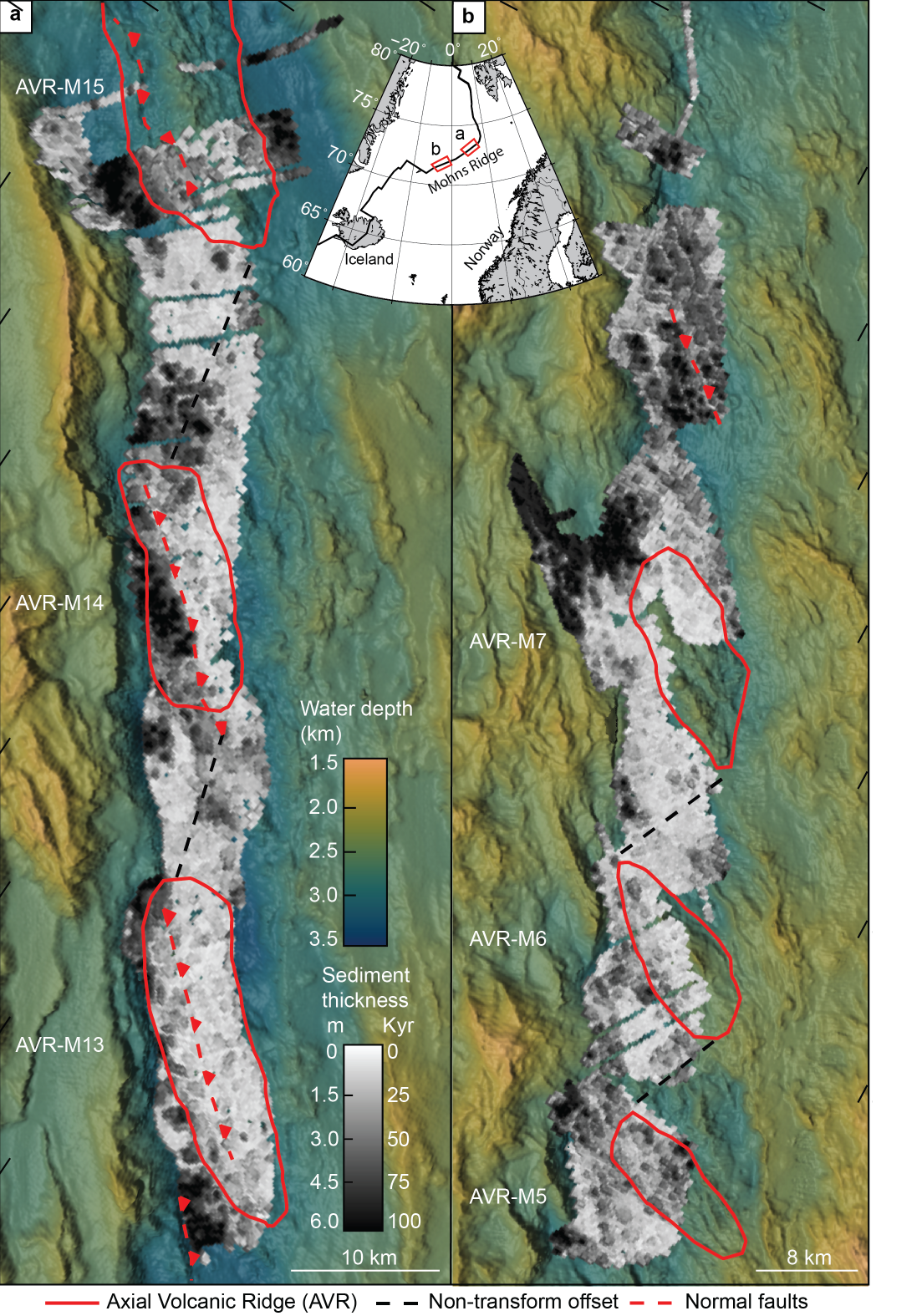

Along the Mohns Ridge, the rift valley is of considerable extent: About 10 – 15 km wide and 1 – 1.5 km deep. The flanks of the rift valley are marked by major faults, and along the valley floor a number of volcanoes protrude.

Across the entire width

One of the main findings of the study is that volcanic activity occurs across the entire width of the rift valley. In comparison, a fast-spreading ridge will only have volcanic activity within a very narrow belt of around a couple of hundred meters.

The Mohns Ridge is, therefore, far more volcanically dynamic than previously thought. This means that the seafloor in this terrain is constantly renewing itself and remains relatively young.

“There has been a lot of focus on the fact that mineral deposits may eventually be buried by sediments, but for those located in the rift valley, it is just as likely that they may be covered by lava flows. This, of course, has an impact on the availability of the resources – we may not be able to detect the deposits that are covered by lava, and they may be difficult to exploit,” says Håvard.

He mentions the discoveries Ægirs kilde and Lokeslottet (both active springs) as examples of deposits that are at risk of being buried by new lava flows. Håvard is more optimistic about the preservation potential of the deposits that are located along faults on the flanks of the rift valley.

There is reason to believe that several of the companies – if or when they are awarded licenses – will concentrate their activities around the Mohns Ridge, which is the most prospective area with regard to sulfide deposits. The research can help exploration companies understand the preservation potential of the mineral deposits and which areas are most suitable.