Polar bears are frequent visitors in Hornsund, and, in spite of their cosy appearance, they are extremely dangerous to humans who are not cautious. To carry a gun when studying rocks onshore is therefore mandatory, as it is also elsewhere on Svalbard. The polar bear is a semi-aquatic marine mammal that has adapted to life on a combination of land, sea, and ice. It depends upon pack ice and marine food for survival. The bear has tapered body streamlined for swimming.

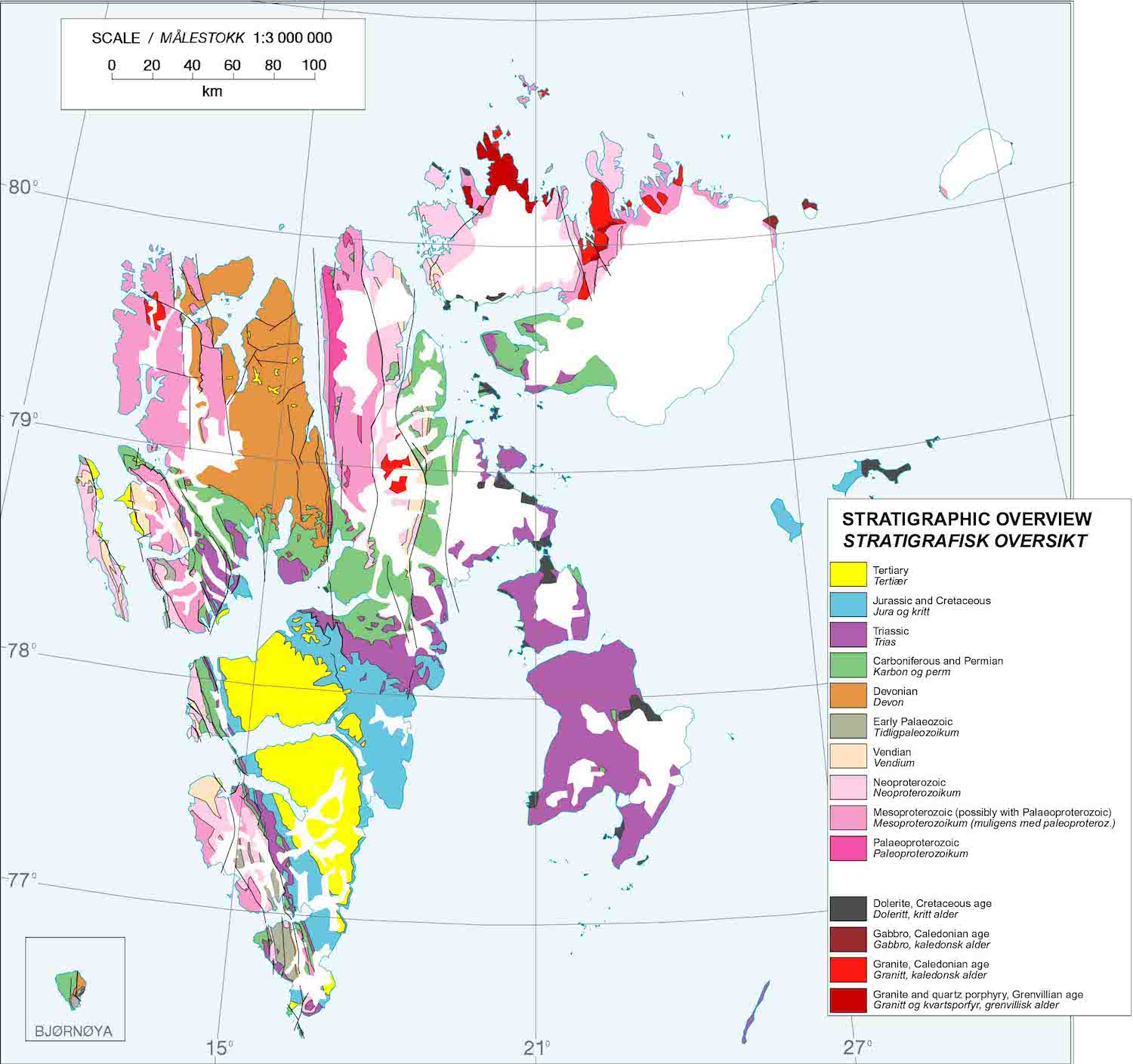

Hornsund is located on the southwest tip of Svalbard where Precambrian, Paleozoic and Mesozoic rocks are exposed. In Early Tertiary times, shearing between the Barents and Greenland plates caused folding, thrusting and uplift of the rocks, and today Hornsund is a key area for studying the Tertiary tectonic history of West Spitsbergen and the western Barents Sea.

Abraham Storck (1644–1708). Dutch whalers near Spitsbergen. 1690. Source: Stichting Rijksmuseum het ZuiderzeemuseumHornsund got its name in 1610, when the British whaler Jonas Poole, with the ship “Amitie”, found shelter here during a storm. The crew that went ashore found some horns from reindeer, and because the fjord packed with ice looked more like a “sund” (narrow seaway), the newly discovered area naturally became known as Hornsund. When you come from the Barents Sea towards southwest Spitsbergen, you may recognize the majestic, alpine Horsundtind (1,431m) from a distance of 75-85 nautical miles.

Abraham Storck (1644–1708). Dutch whalers near Spitsbergen. 1690. Source: Stichting Rijksmuseum het ZuiderzeemuseumHornsund got its name in 1610, when the British whaler Jonas Poole, with the ship “Amitie”, found shelter here during a storm. The crew that went ashore found some horns from reindeer, and because the fjord packed with ice looked more like a “sund” (narrow seaway), the newly discovered area naturally became known as Hornsund. When you come from the Barents Sea towards southwest Spitsbergen, you may recognize the majestic, alpine Horsundtind (1,431m) from a distance of 75-85 nautical miles.

Picture this scene: Majestic mountains stretching up to 1,400 m into the crystal-clear blue sky, the turquoise, flat fjord just beneath, and in the distance you can rest your eyes on scenic glaciers reaching the water and calving into the sea with a roar.We are at Treskelen, a small peninsula on the northern side of the innermost part of Hornsund, a 30km long and up to 12km wide fjord on the south-western coast of Spitsbergen. Hornsund is the southernmost fjord on Svalbard and is located within the Sør-Spitsbergen National Park.

Dedicated Geologists

This morning we have walked along the northern shore and examined a colourful succession of sedimentary strata, starting with continental Devonian and Carboniferous clastics, continuing through Permian marine carbonates and ending in Triassic clastic shelf deposits.

Suddenly, the guy up front shouts out: “Polar bear ahead!” We have already passed some impressive polar bear tracks on our way to Treskelen, and there he is, just some 200-250 m in front of us. “Stop, and stay closely together,” commands Geir Birger Larsen, the expedition leader from Statoil.

If you do not actually encounter polar bears while onshore, you may nevertheless observe that a representative of these huge predators has been here lately. Note the huge claws and the depth of the imprint. Source: Morten SmelrorGeoscientists, as you may be aware of, are usually dedicated to their trade. That is why they do not always stay in line when requested. Some have been on Arctic adventures before, and are not easily impressed by the white, Arctic inhabitants. So when the expedition leader decides it is best to keep some distance from the bear, to terminate the field activities and to call for the zodiack-boat to pick us up, the distinguished Professor David Gee from Uppsala University shouts:

“Give me a gun! I want to see the Jurassic.”

Needless to say, his demand was not accepted.

We are a group of 25 geoscientists from Russia, Norway and Sweden, who have stopped for a day in Hornsund on a field trip around Svalbard. In Hornsund we are guided by colleagues from the Polish Polar Station (Polska Stacja Polarna) at Isbjørn-hamna, (Polar Bear Bay) located some few kilometres further west. Our mission is to study the rocks of Svalbard as a part of a joint VSEGEI-NGU-NPD-Statoil project aimed at making a synthesis of the geological history of the Barents Sea, including Svalbard and the Russian Arctic islands (Geo Base project).

Complex and diverse geology

The geology of Hornsund is complex and diverse, including both Precambrian crystalline and Paleozoic-Mesozoic sedimentary rocks. Its interesting geology and glaciated landscape have for decades attracted geologists and geo-morphologists to this area. The Proterozoic to Cenozoic strata reveal a prolonged and complex tectonic development, so the Hornsund-Sørkapp region is a key to understanding the geological evolution of Svalbard and the western Barents margin.

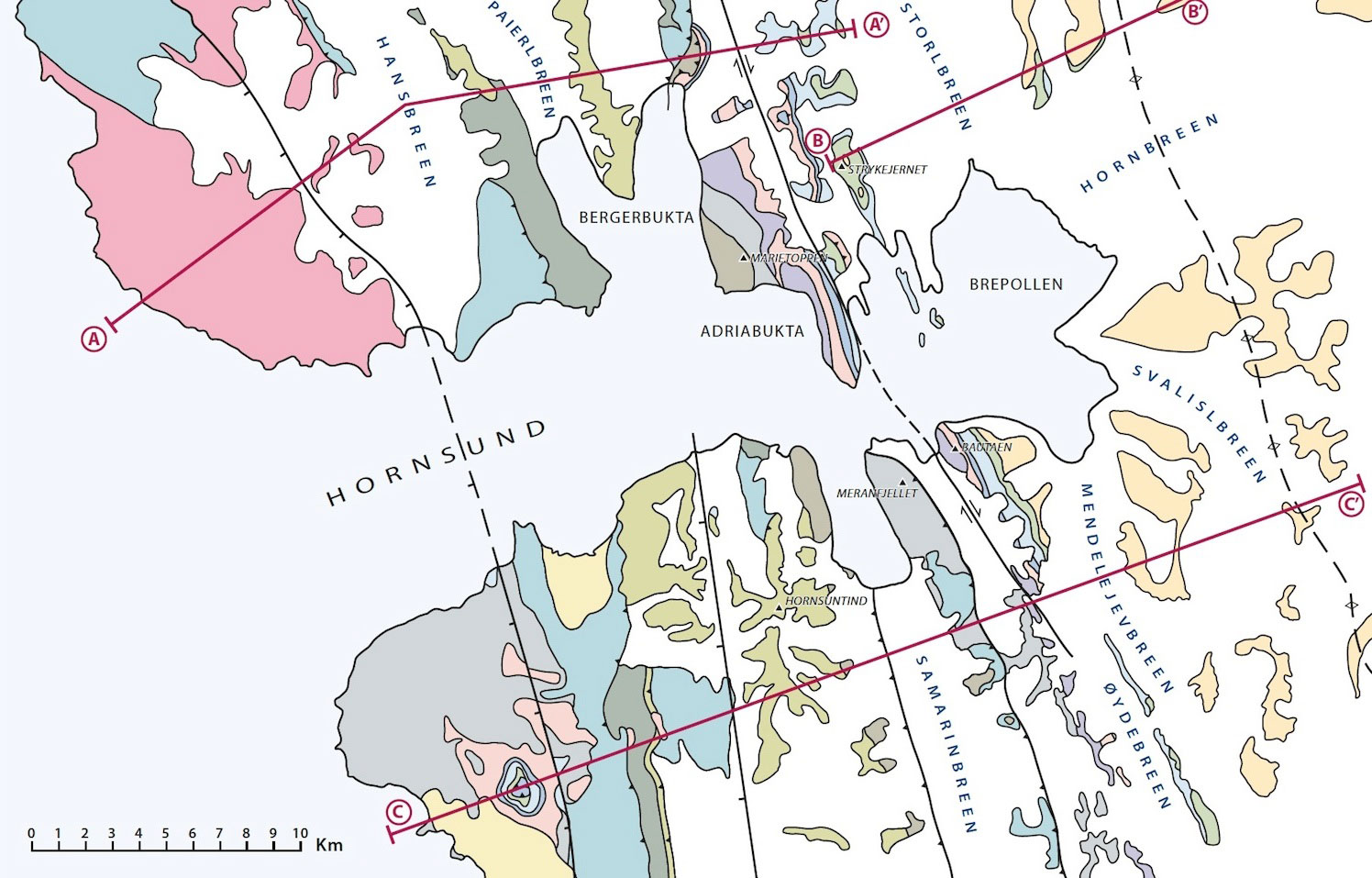

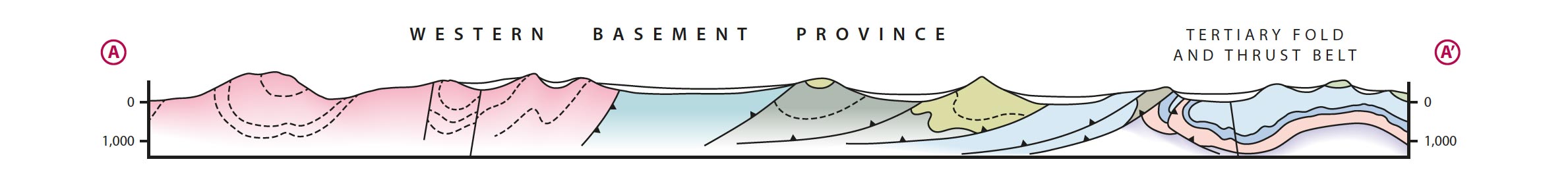

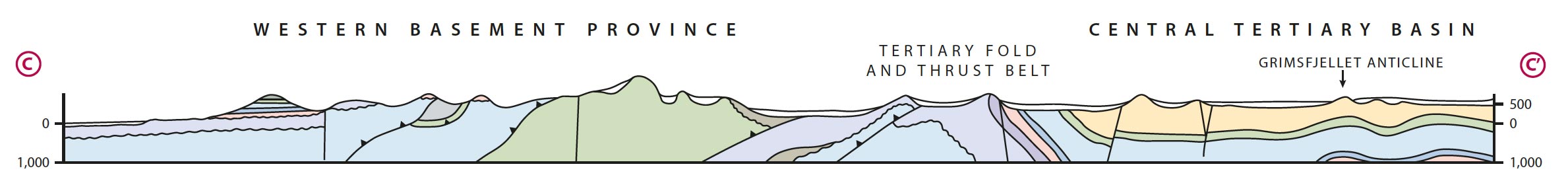

The outer, western part of Hornsund traverses the Sørkapp-Hornsund High, a long-established feature composed of folded and thrusted Caledonian basement rocks, locally unconformably covered by sediments of Late Paleozoic to Mesozoic age. This is part of the north-north-west to south-south-east trending Western Basement Province which extends along the western margin of Spitsbergen.

The spectacular folding of Proterozoic to Mesozoic strata in Inner Hornsund, as seen at Adriabukta, is the southern extension of the north-north-west to south-south-east trending Tertiary Fold and Thrust Belt. This also traverses western Spitsbergen and results from the early Tertiary collision between Greenland and Svalbard. This area also suffered extensive tectonic movements during the Late Devonian (Svalbardian) and Early to Middle Carboniferous (Adriabukta Fold Phase), so that the resulting structural geology is very complex.

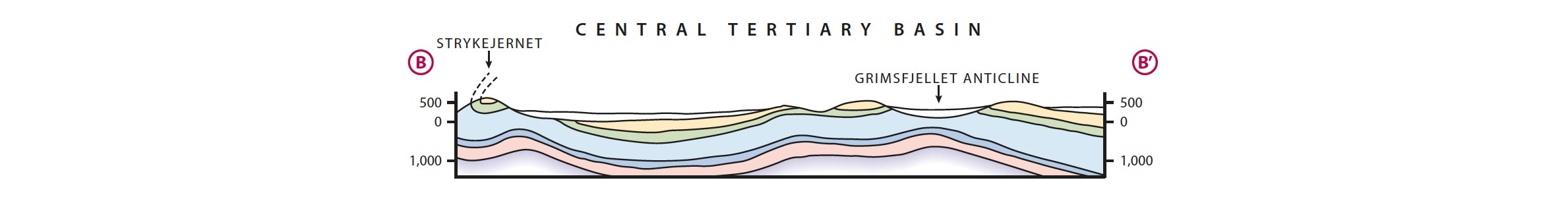

At the end of Hornsundfjord, around Brepollan, we find Cretaceous and Tertiary sediments in the southern part of the Central Tertiary Basin. Folding is increasingly gentle to the east. A prominent north-north-west to south-south-east trending gentle anticline, the Grimsfjellet Anticline, was drilled by two wells, Tromsobreen 1 and 2, in a coastal location to the south-south-east in 1976 and 1987. The second well was a small open hole gas discovery in a carbonate reservoir of Permian age.

Basement comprises micaceous schists of Middle Proterozoic age and Late Proterozoic low-grade metamorphosed sediments including basal conglomerates, phyllites and oolitic and strombolitic dolomites. Cambrian sediments of the Sofiekammen Group comprise clastic sediments and carbonates. The Early Ordovician limestones of the Sørkapp Land Group are responsible for the spectacular Alpine scenery of Mid-Hornsund, including the 1,431m Hornsundtind, the highest mountain in south Spitsbergen, visible from about 150 km away. Late Ordovician sediments comprise dark coloured shales and limestones.

1

1 2

2 3

3 4

4 5

5 7

7 8

8 9

9 10

10

Source map & sections: Bernard Cooper/Bruce Winslade (derived from Norskpolarinstitutt 1993 – 1999)The Caledonian Orogeny resulted in extensive folding and erosion of pre-existing sediments and the initiation of a major north-north-west to south-south-east trending tectonic zone, the Inner Hornsund Fault Zone, which now more or less underlies the Tertiary Fold and Thrust Belt. Syn-sedimentary movement along the westerly throw appears to have been partly responsible for the thick accumulation of alluvial to shallow marine sediment deposited in this area from the Early Devonian to Early Permian.

Source map & sections: Bernard Cooper/Bruce Winslade (derived from Norskpolarinstitutt 1993 – 1999)The Caledonian Orogeny resulted in extensive folding and erosion of pre-existing sediments and the initiation of a major north-north-west to south-south-east trending tectonic zone, the Inner Hornsund Fault Zone, which now more or less underlies the Tertiary Fold and Thrust Belt. Syn-sedimentary movement along the westerly throw appears to have been partly responsible for the thick accumulation of alluvial to shallow marine sediment deposited in this area from the Early Devonian to Early Permian.

Thick deposits of the Early Devonian Wood Bay Group occur with the Samarinbreen syncline to the east of Hornsundtind and outcrop in Marietoppen, north-west of Adriabukta. These sediments consist of steeply-dipping red-coloured sandstones and siltstones. They were overlain by thick deposits of alluvial and fluvio-lacustrine sediments of the Early Carboniferous Billefjorden Group prior to Middle Cretaceous folding.

During the Late Carboniferous to Early Permian, thick successions of alluvial sandstones and conglomerates of the Giesdalen Group accumulated in the Inner Hornsund Trough. The red conglomerates, sandstones and shales and occasional white sandstone of the Hyrnefjellet Formation are well exposed in the Tertiary-aged Hyrnefjellet anticline at Adriabukta. Vertical, well-cemented conglomerates of the Bladegga Member of the Hyrnefjellet Formation form the spectacular peak of Bautaen (473m). The upper part of the Giesdalen Group, the Treskelodden Formation, is more marine and yellowish in colour. There is considerable regional contrast between the alluvial redbed Giesdalen Group fill of the Inner Hornsund Trough and the more massive marine evaporite and carbonate fill of the better-known Billefjorden Trough.

The Late Permian carbonates of the Tempelfjorden Group are only locally present in the Hornsund area while the transgressive, marginal marine, Early Triassic sediment of the Sassendalen Group are much more extensive. These overlie older sediments in the Western Basement Province as shown on Cross section C. The Late Triassic to Early Cretaceous sediments of the Kapp Toscana and Adventdalen Groups are restricted to the Eastern Part of the Tertiary Fold and Thrust Belt and underlie the Tertiary sediments of the Van Mijenfjorden Group in the Central Tertiary Basin.

Wanny; Taxidriver and Bear-hunter

In Horsund polar bears are quite common, and if you enter the area from the sea early in the spring, when there still is sea-ice on Brepollen, you have good chances of meeting the king of the Arctic. One reason is that the polar bear’s favourite food, the ring seal, breeds in the fjord.

In late autumn, the polar bears migrate through Hornsund when the sea-ice is formed on the eastern side of Spitsbergen. Today, the migration routes are monitored by satellites. From the historical records, it appears that the migration routes have been pretty much the same during the past 80 years.

Wanny, a taxi driver in Tromsø, learned stories about the rough life on Svalbard from hunters she drove to the local pubs in the early 1930’s. When she got a chance to go to Svalbard, she did not hesitate, and in only a few days the small, urban woman was transformed into a hunter. She settled at Hyttevika in Hornsund, and in the first season she shot her first polar bear in Isbjørnhamna, close to where the Polish research station is located today. This is typical for how the mountains and places are given a name in Svalbard. For most of them there is an interesting story to tell.

The Polish Polar Station

In connection with the International Geophysical Year in 1957, the Polish Academy of Sciences established a polar research station in Hornsund. A reconnaissance group searching the area for a suitable location had been in Hornsund in the previous summer, and selected the flat marine terrace in Isbjørnhamna. The leader of the expedition that established the station was Stanislaw Siedlecki, a geologist, explorer and climber, a veteran of Polish Arctic expeditions in the 1930’s, including the first traverse of West Spitsbergen.

The research station, which was constructed during three summer months in 1957, was modernized in 1978, in order to resume year-round activity. Since 1978, the Institute of Geophysics, Polish Academy of Sciences, has been responsible for organizing year-round and seasonal research expeditions to the station. Current full-year activities at the station include meteorology, seismology, geomagnetism, ionospheric sounding, glaciology, atmospheric electricity and environmental monitoring. In summers and winters, the station functions as a base for research on geology, geodesy, geomorphology, glaciology, oceanography and biology.

Impressive Glacial Scenery

The coastline in Hornsund has a number of bays with glaciers entering the fjord. Some of these bays first appeared during the last century after the glaciers retreated. As a consequence of the melting glaciers, the whole coastline in Hornsund has expanded. From records going back to 1900, we know that the fjord area has grown by 100 km2 in the 20th century, corresponding to an average increase of 1 km2 per year the recent decades. The records also tell us that some tide-waterglacier-fronts have stepped back with 125 m to 380 m per year since 1961.

At Brepollen, in the innermost part of Hornsund, we find some of the most impressive glacier scenery on Svalbard. From a 1936 topographic map we know that the Storbreen, Hornbreen and Chomjakovbreen glaciers used to form a continuous glacier front. Today Brepollen is still impressive, but has several separated and isolated fronts. West of the monolithic 487m-high mountain Bautaen, the Chomjakovbreen glacier is reduced forming a separate bay, Svovelbukta.

Prepare for rough weather

On the perfect, sunny day we were in Hornsund, a single sail-yacht visited the fjord. On this coast, however, the calm and sunny days are not frequent. Low pressure accumulates on the western coast of Svalbard, and in Hornsund, the combination of high mountains, large valleys, vast glaciers and a long fjord result in unstable weather conditions. When there is complete calm outside the coast of Western Spitsbergen, there may well be heavy wind in Hornsund coming from the east. The wind behaves as if it were running through a tunnel between east and west, across the glacier and in to the fjord.

Acknowledgement

Erling Siggerud, PESGB Svarlbard field trip