It is estimated that there is enough heat within the UK’s coalfields to meet the demands of all the buildings that lie over them. From that perspective, it makes sense to further investigate the potential of extracting water from abandoned mines. This is where the Glasgow Observatory comes in.

Funded by the UK Government and run by the British Geological Survey (BGS), the Glasgow Observatory comprises of a network of twelve boreholes ranging in depth from 16 to 199 m designed to observe how water moves around the abandoned mines over time.

“Using energy from abandoned mines is not new,” as Vanessa Starcher from the BGS explained during a PESGB evening lecture earlier this year. “There are quite a few projects ongoing and in development, particularly in the English mining district. The Glasgow Observatory complements the more commercial schemes as output from the site can subsequently be used to improve systems put in place in the future.”

Farme Colliery

The Glasgow Observatory is located in the southeast of the city on top of the Farme Colliery where almost 500 people were working in the 1920’s. The seven coal seams mined are from the Upper Carboniferous Scottish Coal Measures and have an aggregate thickness of 22 ft or almost 7 m. The depths at which the coals are being found vary between 40 and 100 m.

Drilling into the abandoned coal mines presented a few uncertainties. Rather than just finding an open space filled with water, the possibility also exists of finding the roof to be collapsed, an intact “unmined” coal or just a heap of mining waste. In addition, despite coal seams generally having a laterally extensive nature, in places they have been washed away by fluvial activity at the time.

Data available

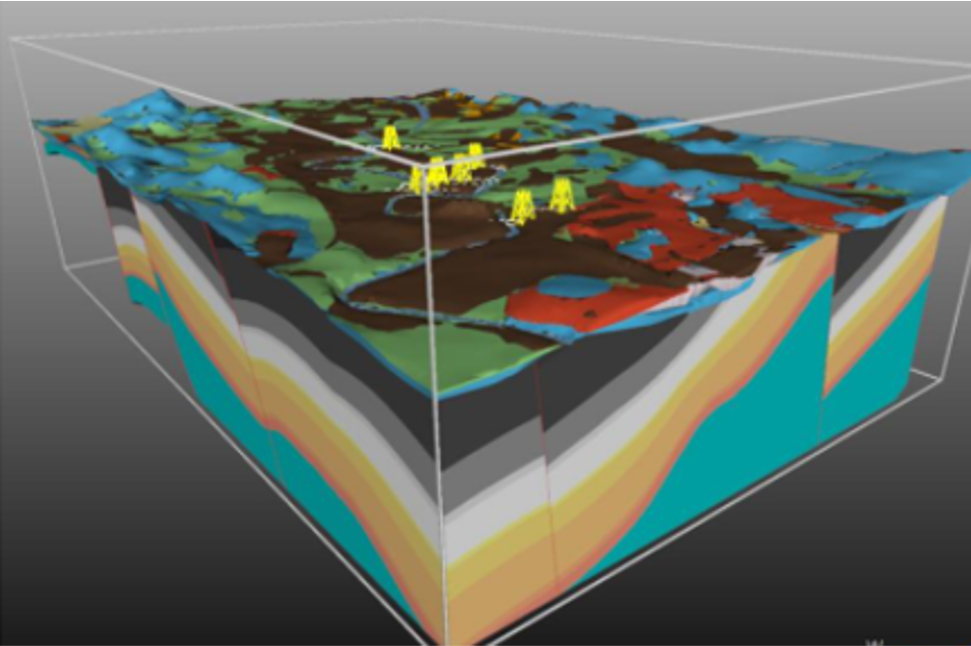

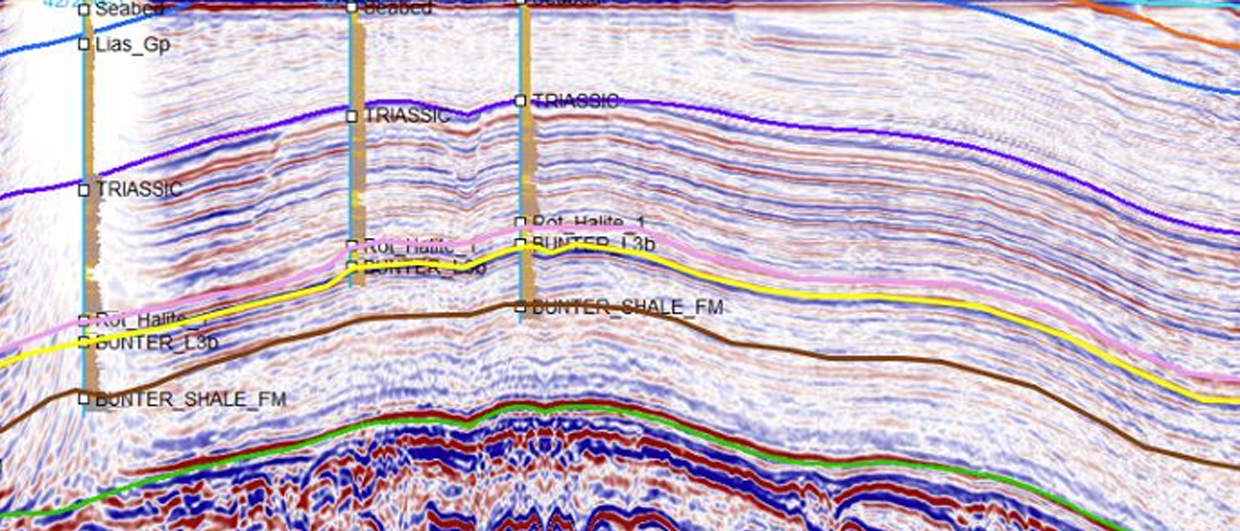

There is a variety of data already available from the testing site for public use. A borehole information pack can be downloaded for each borehole, in addition to a surface water and soil chemistry dataset. 3D models have also been built of both the superficial Quaternary deposits as well as the Carboniferous bedrock. Finally, a seismic monitoring scheme is also in place which is continuously generating data. More datasets are planned to be released in the near future.

Global quieting

One of the unexpected observations from the seismic monitoring schema was the recording of the effect of the lockdown imposed last year. Where previously the weekends were marked by an overall slowdown of background noise, from Mid-March 2020 this pattern can be seen to drastically change towards much lower levels of noise – albeit still with a weekend signal superimposed on it.

Durham Energy Institute

The Glasgow Observatory is ready for researchers to use as a test site. For instance, the Durham Energy Institute has just agreed to team up with the British Geological Survey (BGS) and industrial and governmental experts to assess and address the technical, social, and financial challenges and risks of exploiting disused, flooded coal mines as a source for long-term sustainable heat for homes and businesses in the UK.

HENK KOMBRINK