Geological map of the Gulf of Phang-Nga, modified after Ridd, Barber and Crow (2011). The heavy black lines represent the Khlong Marui Fault Belt, which separates the Phuket Terrane from the Lower Peninsular.For many, Thailand is the epitome of the perfect holiday destination: sparkling blue seas, tropical islands; long, golden beaches; wonderful mountain scenery; and delightful, friendly people. As in many places, much of what is enjoyable here is a direct result of the underlying geology.

Geological map of the Gulf of Phang-Nga, modified after Ridd, Barber and Crow (2011). The heavy black lines represent the Khlong Marui Fault Belt, which separates the Phuket Terrane from the Lower Peninsular.For many, Thailand is the epitome of the perfect holiday destination: sparkling blue seas, tropical islands; long, golden beaches; wonderful mountain scenery; and delightful, friendly people. As in many places, much of what is enjoyable here is a direct result of the underlying geology.

Stretching over 1,600 km from north to south and 780 km at its widest point, Thailand is too geologically varied for a single article, so while the mountains and plains north and east of Bangkok make up most of the country’s land area, here we will concentrate on the Thai Peninsular, which extends nearly 1,000 km from Bangkok to the Malay border and in places is barely 12 km wide. In particular, we will look at the west-central part of the peninsular, centered on the horseshoe-shaped Gulf of Phang Nga, where some of the country’s most popular tourist destinations, including Phuket and Krabi, are located.

Two Plates Meet

The Thai Peninsular runs roughly north to south – the Upper Peninsular – before bending halfway down to trend northwest– south-east at a point marked by the Khlong Marui Fault south of which is the Lower Peninsular.

Two tectonic blocks have been involved in the creation of Thailand: the Indochina Block in the east, and Sibumasu, once part of the larger Gondwana mass, to the west. These drifted together in the Mesozoic, ultimately fusing to form one block, Sundaland. The dividing line between them suggests all of the Thai Peninsular was part of Sibumasu, except in the south, close to the Malaysian border.

A full succession of Paleozoic and Mesozoic rocks is represented in the Lower Peninsular, while Early Paleozoic is absent in the northern area. The oldest rocks comprise Cambrian sandstones and siltstones laid down in a warm shallow sea, while the Ordovician is represented by marine limestone, also with a rich fossil fauna. Silurian black shales were followed by limestones in the Devonian, probably deposited in deep water on the eastern edge side of the Sibumasu Block. Siliclastics followed up to the mid-Permian and these dominate in the Upper Peninsular, although they are much thinner further south.

Marine shelf sedimentation and the widespread deposition of limestones prevailed in Peninsular Thailand in the Late Permian, gradually becoming deeper as Paleotethys was subducted eastwards, which also resulted in the emplacement of submarine granitic and acidic volcanic rocks. By the Early Jurassic, the two plates had merged and Thailand was a single geological entity, with alternating marine and non-marine environments found in the Jurassic in the peninsular area. By the Cretaceous, continental deposition dominated, including claystones, siltstones, sandstones and conglomerates, probably deposited by meandering rivers and alluvial fans.

The Tertiary has been studied extensively in Thailand because of its importance in hydrocarbon and minerals exploration, and more than 70 intermontane and rift basins have been identified, including many offshore. However, only a few small Tertiary basins have been recognized in the peninsular, including one in Krabi Province.

Picturesque Phuket

The island of Phuket was one of the first places in the country to be discovered by holidaymakers and is now quite built-up and busy, with an international airport, although it still retains some quieter areas. Separated from the mainland by a narrow 500m creek, it forms the western side of Phang Nga Gulf and lies at the inflection point of the Thai peninsular. Geologically, it is significant for giving its name to the Phuket Terrane, which dominates the Upper Peninsular and is sandwiched between two major fault belts: the north-east to south-west Three Pagodas Fault in the Upper Peninsula and the south-south-west – north-north-east trending Khlong Marui Fault to the south.

The Phuket Terrane mostly comprises rocks of the Late Carboniferous to Early Permian Kaeng Krachen Group, which is predominantly a thick, poorly-sorted pebbly mudstone (diamictite) containing some cobble or boulder-sized clasts, with limestone and shale layers. It is thought that the Phuket Terrane material was deposited in a glacio-marine environment in a rift formed as Sibumasu split from Gondwana. Similar rocks are found in a narrow band stretching from Sumatra to south-west China. The Khlong Maru Fault, which passes just to the east of Phuket, appears to have been the eastern edge of the rift, as similar-aged rocks are thinner in the Lower Peninsula, with less diamictite. On Phuket the Kaeng Krachen Group outcrops mostly along the eastern side of the island, forming headlands in the south-east at Cape Panwa and Ko Sire.

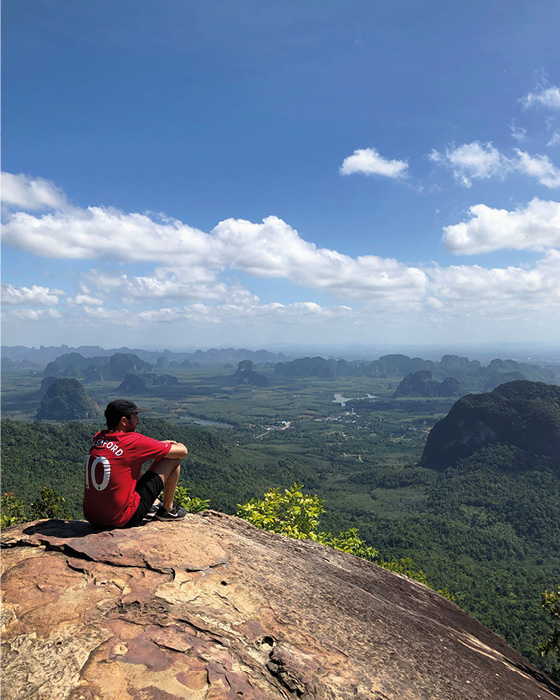

Much of Phuket itself is composed of medium-grained granite and granodiorite intruded into the sediments of the Kaeng Krachen Group as Sibumasu was subducted beneath the Indochina plate. These granites are part of the Cretaceous Western Granite complex running from Phuket northwards into Myanmar in a belt of small batholiths and isolated plutons. They form the mountains, up to 400m high, that dominate the landscape in Phuket. Many tours take visitors to admire the stunning viewpoints, such as Karon in the south of the island, Laem Singh in the west and Promthep Cape, a popular sunset viewing point at the southernmost tip of the island. From the Big Buddha site in the center of the south-west mountains one can have a 360° view covering much of Phuket – but you may have to share it with quite a few other visitors. The mountains also offer the traveler excitements such as mountain biking and jungle trekking.

James Bond Was Here!

Many visitors to Phuket take a boat trip to northern Phang Nga Bay to visit what is commonly known as James Bond’s Island, which featured prominently in the 1974 movie The Man with the Golden Gun. The bay is studded with picturesque islets formed by vegetation-clad, sheer-sided limestone pillars, many eroded around their base, creating a stunning seascape where the rocks seem to float on the sea. They are composed of Ratburi Limestone, which was deposited on the Kaeng Krachen Group from the Early Permian, as a large carbonate platform rapidly covered much of Sibumasu as it moved into more temperate and eventually sub-tropical waters in the Late Permian. Older sections of the Ratburi Limestone tend to be a dark gray well-bedded muddy limestone with chert nodules, while the upper member is lighter and more massive.

After uplift the wind, waves, water currents and tides gradually eroded the platform until, aided by tectonic movements, its remnants can now be seen throughout the area as dramatic isolated small islands, which can be tens of meters in height and just a few meters across at their base. Boats trips from either Phuket or Krabi take in a number of the islands, stopping for snorkeling or visiting the ‘sea gypsy’ village of Koh Panyee. It is also possible to explore them by sea kayak and to discover caves and hidden lagoons – all amazing experiences.

The islands are part of Ao Phang Nga National Park which also includes the largest area of native mangrove forest remaining in Thailand, with rare birds and animals; well worth a visit by kayak or raft.

Cliffs and Caves

Traveling further east and then south round Phang Nga Bay we pass through a less touristed area dominated by Quaternary sediments, although there are still ample opportunities to explore the mangroves and limestone cliffs of the coastline, as well as to admire the karst hills rising steeply several hundred meters out of the flat inland scenery, before reaching the Krabi area. In recent years this has become a mecca for backpackers, attracted by the laid-back atmosphere and the plentiful opportunities for adventure sports such as climbing, hiking and sea kayaking. The abundance of these activities is again mostly due to the Ratburi Formation karst limestone cliffs and islands, particularly around Railay Beach, which, due to the surrounding sheer cliffs, is only accessible by boat from either Krabi town or the tourist center of Ao Nang. The limestone here is made more dramatic by alteration and staining of the white and gray rocks with yellow streaks and by dramatic stalagmites hanging from them. Also worth a visit are the pools surrounded by towering forested cliffs, created when coastal caves collapsed to form a lagoon, and often only possible to enter by swimming or kayaking through the cave entrance.

The small Tertiary-aged Krabi Basin, centered on the town of the same name, has been well studied as it contains three open pit coal mines. Although now considered an over-simplification, for some time all Tertiary rocks in Thailand were described as being part of the ‘Krabi series’. The Paleogene sequence here passes from non-marine silts and clays to gradually coarser sediments laid down in a brackish or fluviomarine environment. There are abundant fossils in these beds and a major tourist attraction is the so-called ‘Fossil Beach’, situated at Laem Pho between Krabi and Railay, where pavements of an argillaceous fossiliferous limestone of Oligocene-Miocene age can be explored in the intertidal zone. The site has information notices that suggest that the fossils, predominantly gastropods, were living in freshwater lakes in which plant remains were also deposited, forming thin lignite bands.

Phi Phi Problems

Lying a 40-km ferry ride south-west of Krabi is Koh Phi Phi – actually several small islands, the two largest being linked by a narrow isthmus of Quaternary sediments. The archipelago is predominantly composed of Ratburi Limestone, with its classic steep-sided cliffs dropping into the sea, although on Phi Phi Don, the largest island and the only one where tourists can stay, the underlying Kaeng Klang group is exposed in the south and east. It contains less diamictite than on the Phuket Terrane and comprises black shales and poorly sorted sandstones, with some evidence of its glaciomarine origin in the form of dropstones.

Relatively untouched in 2000, the making of the Leonardo di Caprio film The Beach on the smaller of the two linked islands introduced Phi Phi to the world and it is now a popular destination, particularly for younger travelers, who enjoy it’s beauties by day and party by night. Diving or snorkeling on the coral reefs in the crystal waters around the smaller islands has become a great draw but unfortunately tourism has been detrimental to the ecosystem; at one point Maya Bay, where the filming took place, received thousands of visitors each day. The Thai authorities have attempted to rectify the problem by temporarily closing the beach and other areas and this, coupled with lack of tourists due to Covid-19, appears to be having some impact.

Peaceful Koh Lanta

Continuing our journey down the eastern side of the Phang Nga Gulf we travel through relatively flat Quaternary and Tertiary sediments, with a distant view of inland Mesozoic hills, before hopping onto a ferry for a short crossing to Koh Lanta Yai; a quieter destination, with less dramatic scenery than further north as the island is dominated by Upper Paleozoic siliclastics. There is little documentation on the actual rocks making up the island, but it is thought that they are primarily siliclastics of the Upper Carboniferous Kaeng Krachen Group, unconformably underlain by Lower Carboniferous siliclastics and possibly Devonian shales.

It is a delightful place to visit, with long sandy beaches, small coves, a hilly rainforest interior complete with hikes to a ‘Tiger Cave’, and the picturesque Lanta Old Town, which hosts century-old wooden houses built on stilts jutting into the sea, surrounded by mangrove forests. This is a great jumping-off point for snorkeling, diving and kayaking trips out to surrounding islands, where the karst once again predominates.

So, at the end of our tour, finnd a nice viewpoint, sit back and enjoy the ambiance as the sun slowly sinks into the sea in yet another spectacular sunset. Beautiful!

References

- Ampaiwan, T., Hisada, K-I. and Charusiri, P. 2009 Lower Permian glacially influenced deposits in Phuket and adjacent islands, peninsular Thailand. Island Arc 18, 52-68

- Benammi, M., Jaeger, J., Chaimanee, Y., Suteethorn, V., Ducrocq, S., 2001Eocene Krabi Basin (southern Thailand): Paleontology and magnetostratigraphy. Geological Society of America Bulletin 113(2)

- Harper, S. B., Morphology of Tower Karst in Krabi, Southern Thailand. Department of Geology, East Carolina University, Greenville, NC 27858,

- http://www.dmr.go.th/main.php?filename=GeoThai_En

- Metcalfe, I., 2011. Palaeozoic–Mesozoic history of SE Asia. In Hall, R., Cottam, M. A. &Wilson, M. E. J. (eds) The SE Asian Gateway: History and Tectonics of the Australia–Asia Collision. Geological Society, London, Special Publications, 355, 7–35. DOI: 10.1144/SP355.2 0305-8719/11/$15.00 # The Geological Society of London 2011.

- Ridd, M.F., and Watkinson, I. 2013. The Phuket-Slate Belt terrane: tectonic evolution and strike-slip emplacement of a major terrane on the Sundaland margin of Thailand and Myanmar. Proc. Geol. Assoc. http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.pgeola.2013.01.007

- Ridd, M.F., Barber, A.J., and Crow, M.J. (Eds), 2011. The Geology of Thailand. Geological Society, London

- Sautter, B., Pubellier, M., Jousselin, P., Dattilo, P., Kerdraon, Y., Chee Meng Chong, Menier, D. 2017. Late Paleogene rifting along the Malay Peninsula thickened crust. Tectonophysics 710–711 (2017) 205–224

- Shawe, D. R., 1984 Geology and mineral deposits of Thailand. Government of Thailand and the Agency for International Development, U.S. Department of State. Open file Report 84-403