This week, I came across the concept of finding oil in synclines on a number of unrelated occasions. It simply shows how diverse geology and exploration are.

The first example is from the Michigan Basin in the US, where oil was found in Ordovician dolomites in subtle synclinal structures in the so-called Albion-Scipio trend. This all unfolded in the 1950’s, seemingly driven by a psychic who dreamed that the landowner of the place where the well was drilled had walked across her land with sticky stuff on her hands.

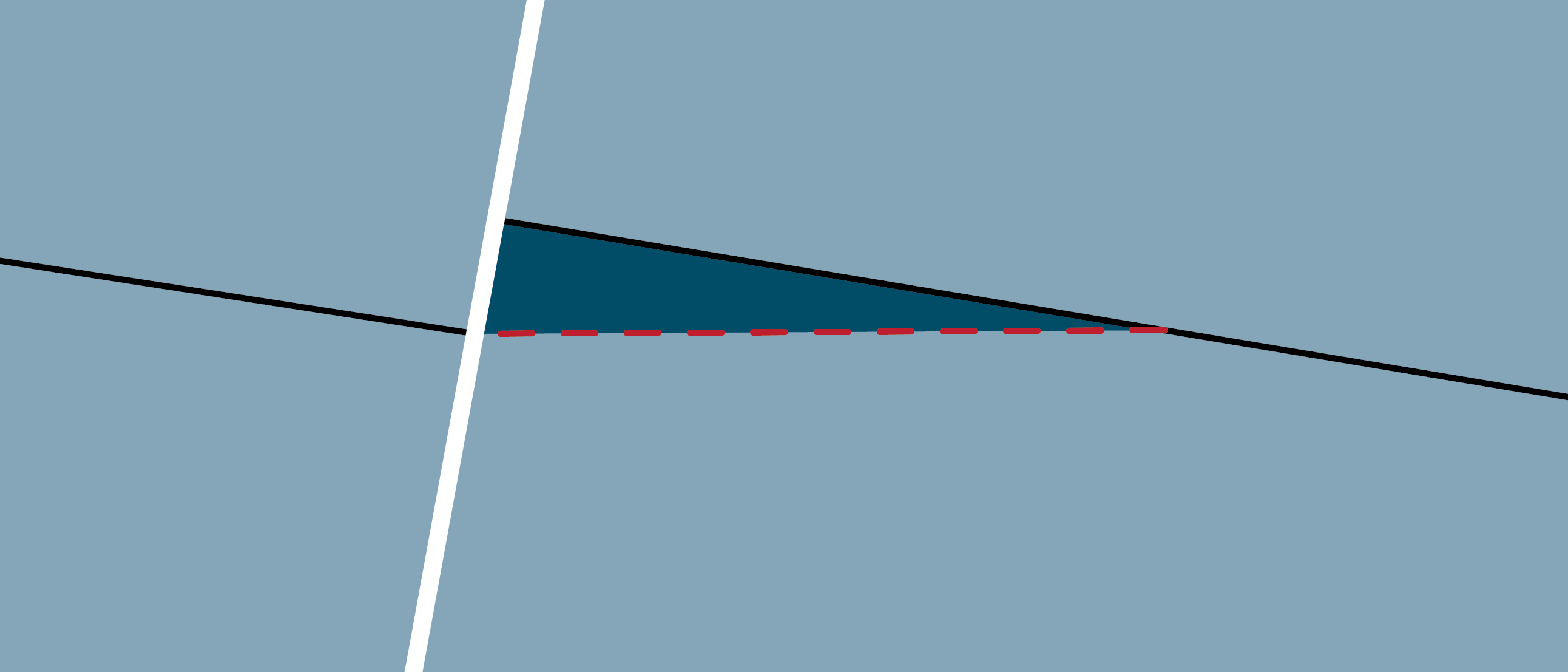

The bottom line is that oil in this case was found more or less driven by luck and not by chasing a geological concept. The concept came later, namely the presence of reactivated basement faults that had caused fluid flow along the fault planes in the overlying carbonates, resulting in the development of a narrow fairway of vuggy, fractured and porous dolomite. Away from the fault zone, wells found a completely tight limestone instead.

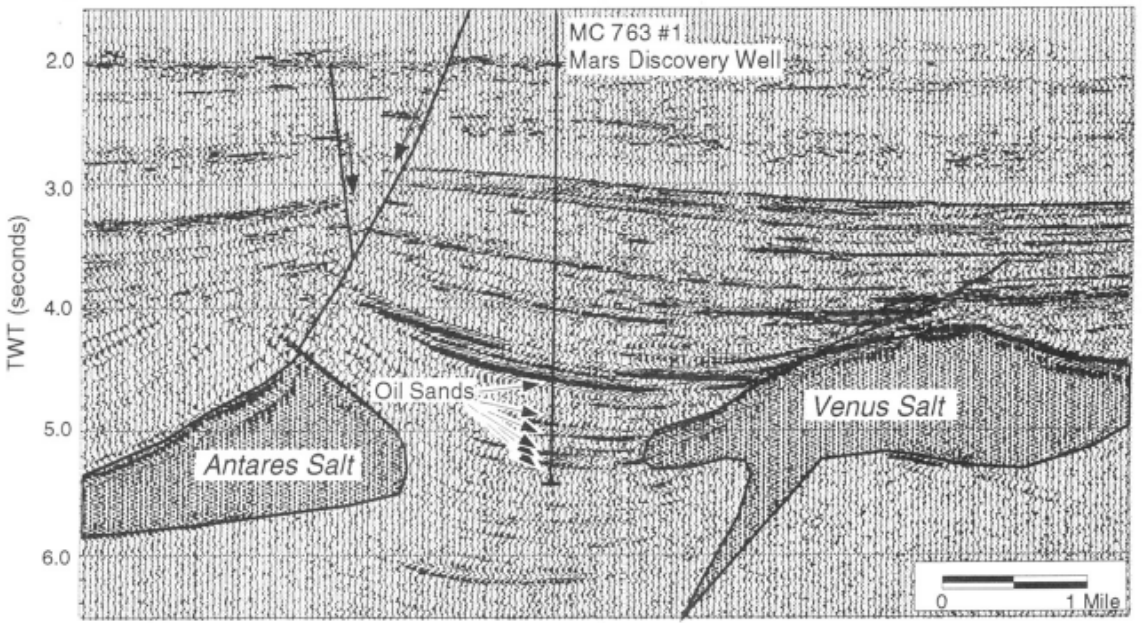

Many years later, in 1989, the Mars field in the Gulf of Mexico was found, also in a synclinal structure. This time, there was no psychic involved, but the latest generation of seismic data, a Direct Hydrocarbon Indicator (DHI), and creative minds pulling together ideas on how such a structure may work.

I spoke to Henry Pettingill – one of the geologists behind the discovery of Mars – about it the other day. He said that nobody believed in the concept of finding oil in a syncline when Shell applied for the block in which Mars was going to be found. It was only after its discovery that many others started applying for similar acreage as well. But did it lead to another Mars-like discovery? “Maybe not so much”, Henry told me. “Mars seemed like a bit of a unique find.”

Reflecting on that, what both the Albion-Scipio and the Mars discoveries have in common except from the fact that they occur in synclinal structures is that subsequent exploration did not bring the exploration success along the lines of the new exploration concept. Is that proof that finding oil in synclines is probably more of an exception than a rule? Another look at these two examples is required.

In the case of the Michigan Basin, one might argue that the exploration concept is valid and that it could be reasonably assumed that in other places where fault reactivation had occurred, oil could also be found. Maybe it is the subtlety of the synclinal structures and the quality of the seismic data that prevented an easy identification of the next successful drilling target.

In the case of Mars, Henry told me that he and his colleagues had mapped a large kitchen area below, with all the generated hydrocarbons being funneled through what became the Mars structure. Maybe it was that particular source configuration that made Mars work. So in this case, it indeed looks as if another favourable factor was required to trap oil in a syncline.

No doubt there are other examples of oil in synclines. But what these two cases show, in my view, is that either an element of luck or technical advancements in combination with a sense of curiosity are required to discover these resources. And in case of the GOM, where seismic data acquisition has progressed to an extent that Mars now looks like a shallow drilling anomaly – in the words of Henry – it can equally be suspected that deeper and maybe equally exciting structures exist. And surely, there could well be another Albion-Scipio trend lurking beneath the hills of Michigan too.