Any exploration well carries risk, and ultimately, it is the drill bit that will either prove or disprove a play concept. In South Korea’s Ulleung Basin, despite the presence of a small number of gas finds, one of the risks when it comes to further exploring its potential is the age of the basin and its infill – has there been enough time for gas to migrate into the omnipresent deltaic and related deep-marine sandstones? The age of the main reservoir targets is Miocene, with subsequent Plio / Pleistocene burial required to “switch on” the associated kitchens.

It is a question that makes even more sense when one realises that the source rocks of the thermogenic gas that is known from the largest gas field – Donghae – has never been drilled to date. Is it an organic-rich interval at the base of the Ulleung Basin’s sedimentary infill, or is it rather the more dispersed organic matter that forms part of the more distal and marine succession of the sedimentary wedge? It makes petroleum systems modelling quite a tricky exercise.

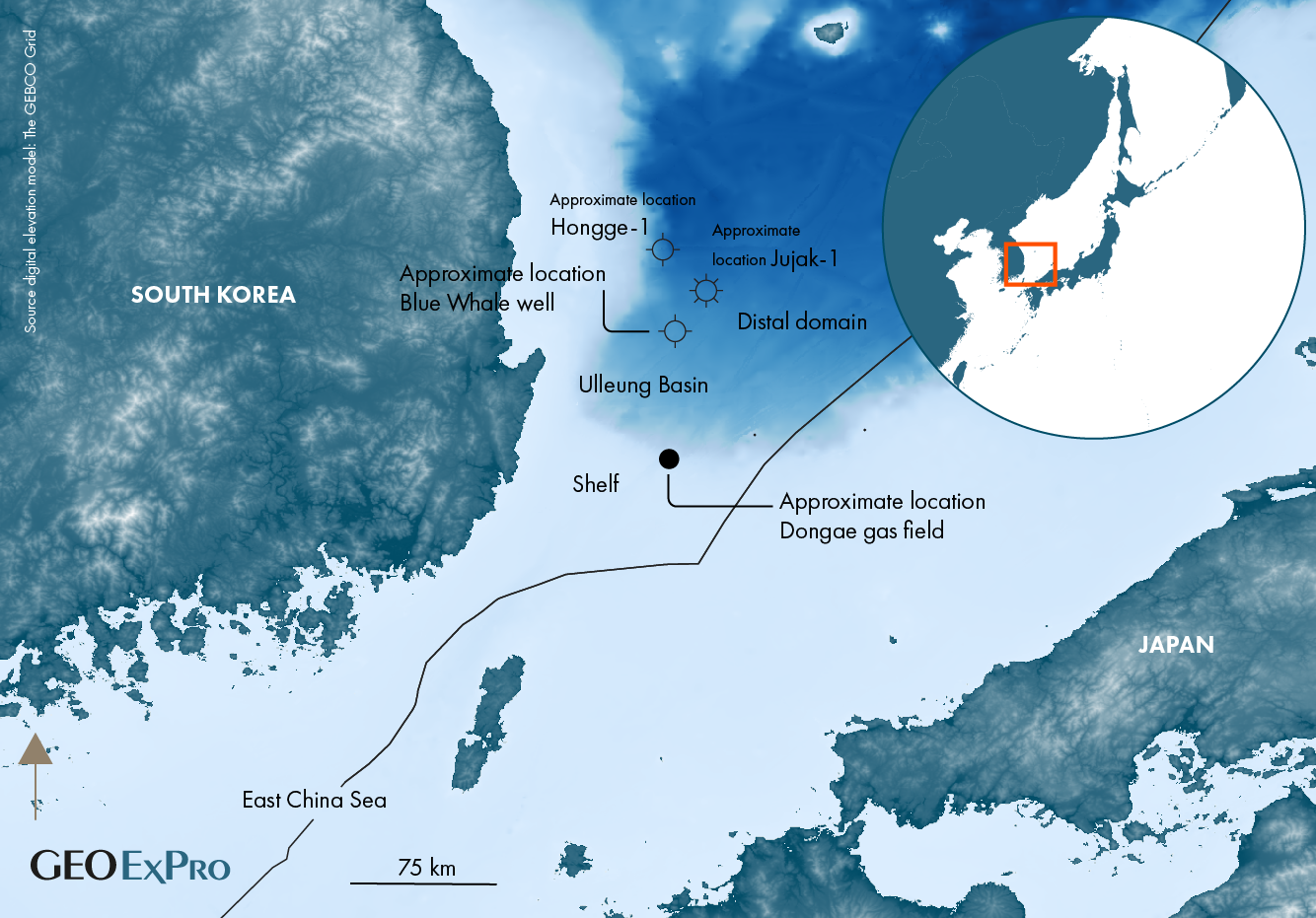

Thus far, Woodside and KNOC have drilled the most northerly located wells in the basin (Jujak-1 and Hongge-1). Hongge-1 drilled a closure along a transform zone, where the reservoir was ultimately contaminated by significant amounts of CO2.

The timing and duration of gas generation must certainly be questions that have been asked by operator KNOC after drilling the recent dry Blue Whale well in Korean waters. The well was highly anticipated, not only by the Koreans themselves but also by operators that had previously been looking at the Ulleung Basin. With a gas-hungry market close by and the likelihood of obtaining star status when hitting a giant, there is certainly an appeal to exploring this part of the world.

Reservoirs are aplenty. The Ulleung Basin – even when many Koreans will not like this – are ultimately sourced and transported by major fluvial systems that derived from the South China Sea. Small tributaries from the Korean peninsula – the more favourable candidates for the Koreans – would certainly not have resulted in such an amount of juicy reservoir sands delivered. This preference for locally sourced sands is not unique to the Koreans, by the way – a similar story can be told about Israel and their preference to source the Tamar reservoir sands from their country rather than from the Nile and its precursors. But that is a by-the-by.

The Blue Whale well was dry, but that doesn’t mean that there is no exploration potential left. There are multiple – albeit subtle – plays to be further explored, both in the deep-marine as well as in the more shelfal realms of the northeasterly-prograding depositional system.