Given the current price environment and concerns about security of supply, one of the things Europe seems to increasingly agree on is the fact that the energy mix should be more diversified.

Yet, oil and gas will remain an important part of the energy mix in the foreseeable future, which is also becoming more and more accepted.

However, as domestic oil and gas production is declining, any serious attempt to prove significant volumes is to also add frontier exploration in the mix again.

This would be a break from current exploration strategies in the wider North Sea area, which is dominated by near-field drilling. Even though the success rate of this type of exploration is higher, the small volumes encountered will slow the decline in overall production at best.

Attend the NCS Exploration – Recent Discoveries Conference, 8-9 June in Oslo and hear about recent exploration highlights across the Norwegian Continental Shelf.

What is really needed is the courage to test new plays that have so far not been sufficiently targeted, if there will be a chance to find something of a Johan Sverdrup or Groningen equivalent.

In that regard, a short article published by Dag Karlsen on geoforskning.no last week provides food for thought. As Karlsen explains, well 6609/11-1 drilled in the Norwegian Sea encountered a 20-cm thick oil-impregnated sand interval in the Jurassic.

Subsequent analysis showed that the oil was identical to the oil produced from the Beatrice field in the Moray Firth, Scotland. In turn, this suggested that the oil found in the Norwegian Sea is likely to find its origin in Devonian lacustrine source rocks, as this is also though to be the main contributor in Beatrice.

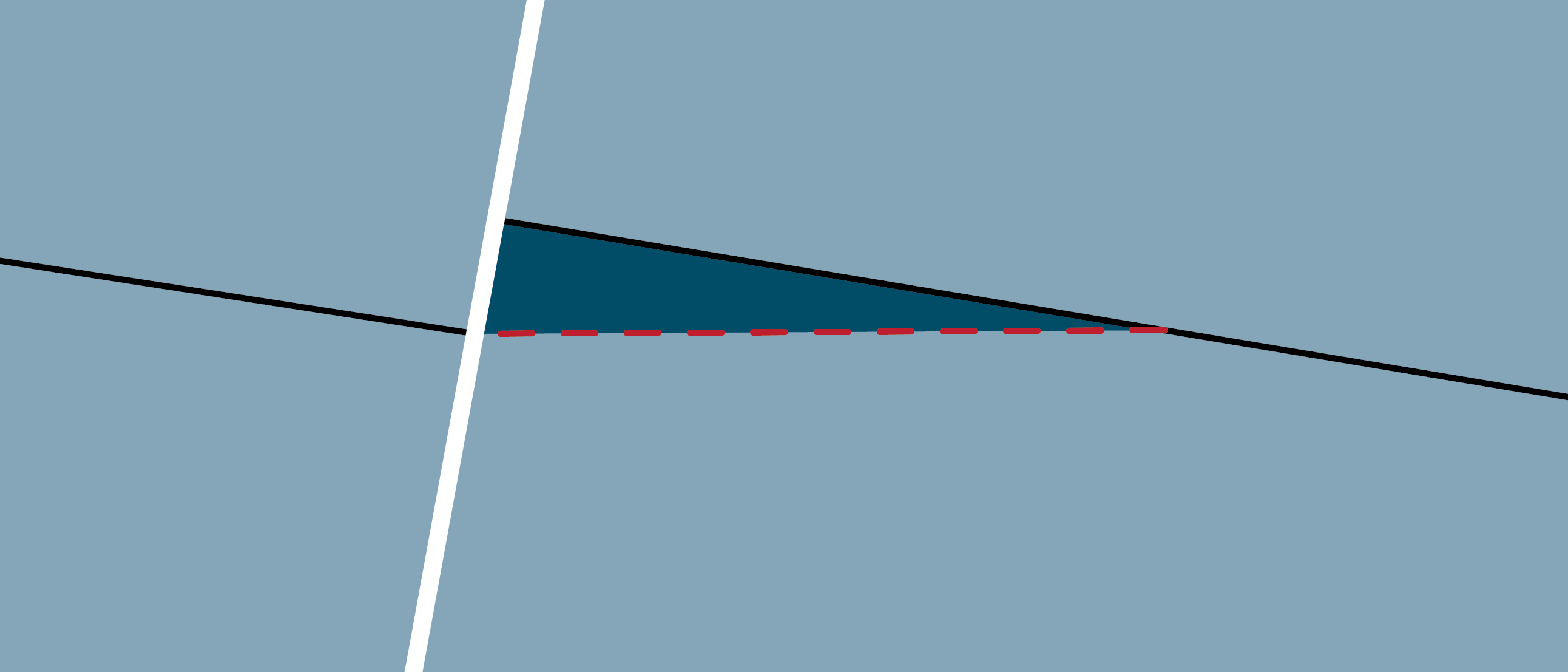

Karlsen further argues that the structural setting of the Norwegian Sea in Devonian times was similar to how the Moray Firth looked like: a setting of increasingly extensive pull-apart basins that developed as a response to the collapse of the Caledonian orogeny.

The discovery of Devonian-sourced oil in the Norwegian Sea should therefore be considered as one of those hints to the existence of another oil source rock, which in turn should spark some interest in exploring the area and possibly look at structures that could have been charged from this source.

Why is it important to use this example? It is these hints of a previously ignored source rock that may ultimately lead to the discovery not only of a new big field, but even of a new play. Only that will really turn the tide of European hydrocarbon dependency, and no doubt Putin will be taking note of that.

HENK KOMBRINK