Field outlines can sometimes be slightly misleading in the sense that a big polygon on a map can leave the impression that a field is huge, whilst in reality the volumes can be moderate to small because the thickness of the reservoir is very restricted or more heterogeneous than foreseen.

This observation certainly applies to the Cretaceous play in the Norwegian Sea. When viewed on a map, it looks as if these discoveries are way bigger than their mostly Lower-Middle Jurassic counterparts, but a close look quickly reveals that it is the thickness and heterogeneity forming the limiting factors.

Take the Marulk and neighbouring Alve field (see map above). Marulk produces gas from both the Lysing and Lange formations and had an original In Place volume of 82 MMboe. Alve, which is reservoired in Lower-Middle Jurassic rocks of the Ile and Tilje formations, “looks” much smaller than Marulk, but contained an In Place volume of 104 MMboe.

The same applies to the Cape Vulture discovery, for which a recoverable volume of 26.7 MMboe is published. Again, it is clear that the size of the polygon is not at all representative of the volume.

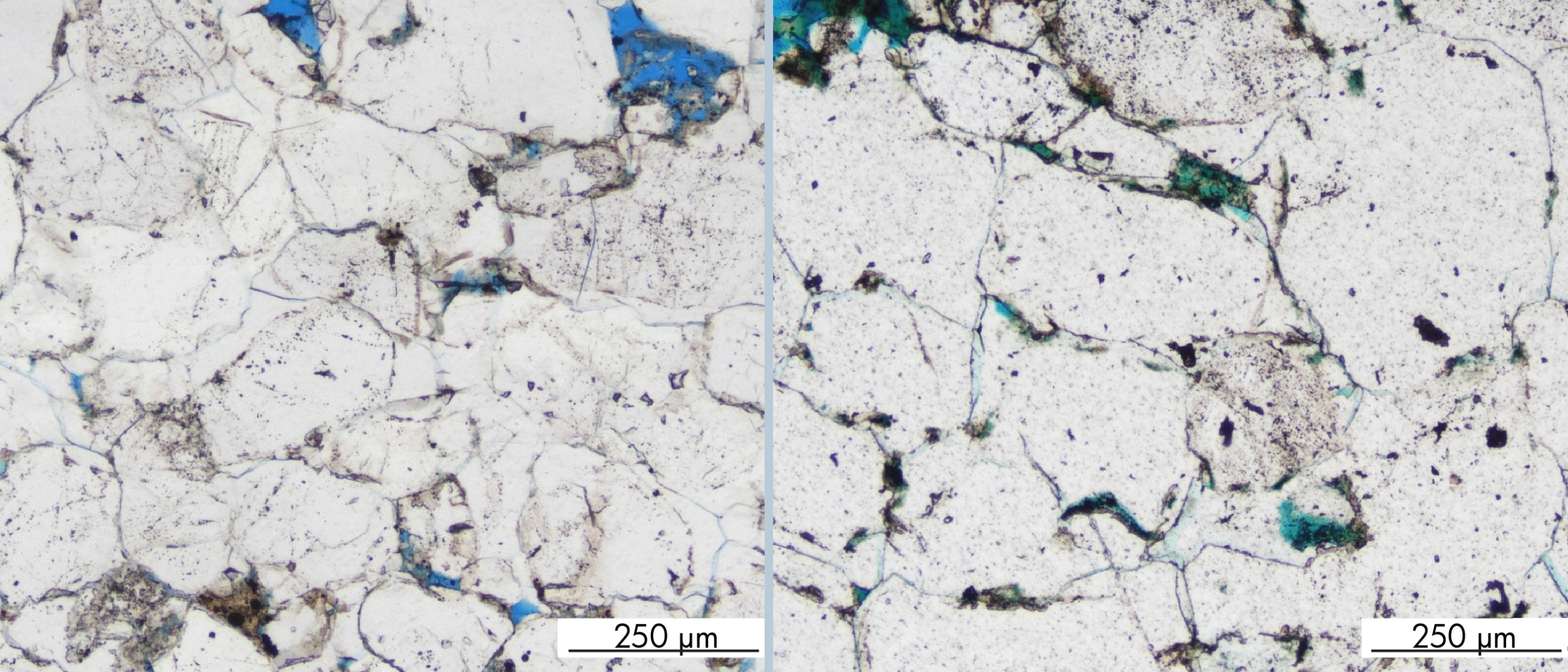

Not only are the Cretaceous Lysing and Lange turbiditic sandstones of a thin and heterogenous nature, trapping mechanisms in the Cretaceous are probably also more subtle than in the Jurassic, as the cross-section below illustrates. The Jurassic fields often occur in nicely tilted fault blocks with sometimes significant columns, where the Cretaceous of the Norwegian Sea is much more of an undisturbed drape of sediments over the structurally more complex Jurassic “basement”.

These observations probably explain why the Cretaceous did not play a significant role in exploration in the area for a long time. However, as seen in the North Sea as well, now that the classic reservoirs are running low on reserves, the focus has changed towards the more challenging prospects. The 6507/5-3 well drilled in 2000 was a game changer in that sense, as it was the first well in the Nordland area that was drilled with the aim to de-risk a Cretaceous reservoir. It proved gas in the Snadd prospect, later renamed as the Ærfugl field.

Against this backdrop, Equinor has now spudded appraisal well 6507/3-14 in the southwest corner of the so-called Black Vulture discovery announced in 2019 (see map above). Looking at the volume range cited for the Black Vulture discovery – from 1 to 50 MMboe – it is not a surprise why it is now further appraised in an attempt to narrow down the range.

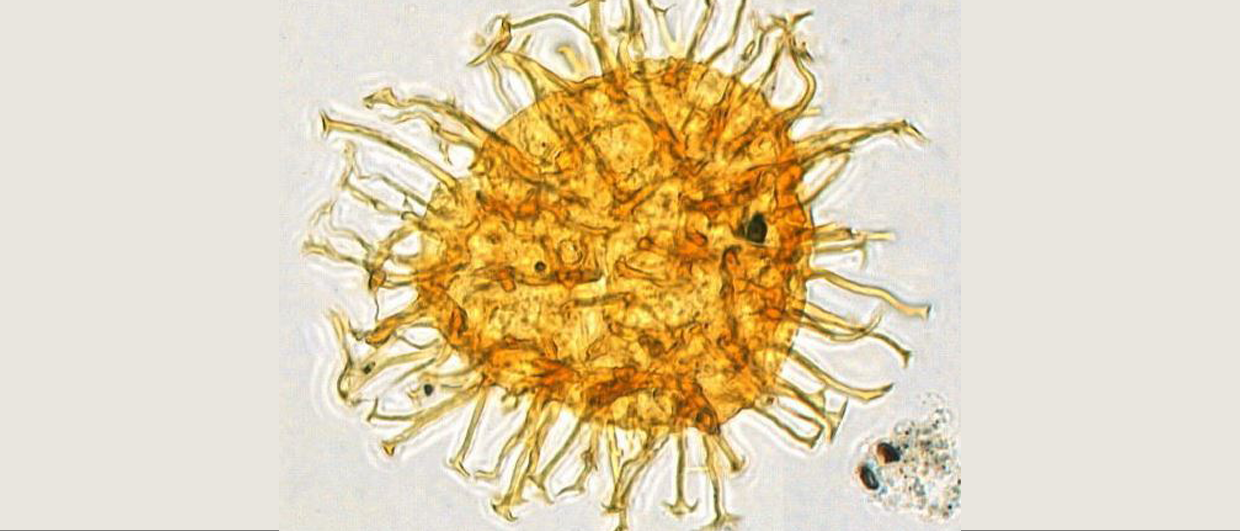

Lined up for drilling later this year is the Egyptian Vulture prospect a little further to the south, located in the heartlands of the Norwegian Sea between the Tyrihans and Maria fields. Also an Upper Cretaceous turbidite prospect, it clearly demonstrates the continued interest in this play.

HENK KOMBRINK