The super-giant East Baghdad oil field lies in the heavily populated outskirts of Baghdad. Can it be successfully and safely exploited?

Prior to 1956, the eastern part of the Baghdad Governorate was separated from Baghdad City by an earth barrier called the Nadhim Pasha Dam, established in 1908 to protect the city from the annual floods of the Tigris River. Consequently, the area was underpopulated apart from isolated settlements, where peasants from southern Iraq built shanty houses to live and find work in the city. In 1956, however, the annual floods were permanently prevented by the construction of the Tharthar Dam, 100 km north-west of Baghdad, and the area east of the original city became available for building.

Sadr City now covers much of this eastern edge of Baghdad. It was built in 1959 by Prime Minister Abdul Karim Qassim and later unofficially renamed Sadr City (after Ayatollah Mohammad Mohammad Sadeq al-Sadr). A public housing project neglected for many years under Saddam Hussein, Sadr City has a population of about a million residents, and the districts to the south-east and north-west of it are also heavily populated urban areas.

The super-giant East Baghdad oil field is situated directly to the east and south-east of Baghdad, underlying these heavily populated outskirts, and crossing both the Diyala and Tigris Rivers. It extends further north-westwards into the Salah ad-Din Governorate, where the area is densely covered with horticulture and fruit trees. Although initially discovered in the 1970s it remains very underdeveloped, primarily due to the political, practical and health and safety issues involved with exploiting an oil field in an urban area.

The teeming modern city of Baghdad is underlain in its eastern suburbs by by a super-giant oil field. (Source: © 123rf.com/Rasoul Ali)

Exploring a Giant Field

Prior to 1960, early exploration work in the East Baghdad area was carried out by the Iraq Petroleum Co. group using gravity and seismic surveys, and in 1974, a Romanian land crew undertook further land seismic in the East Baghdad area for the Iraqi National Oil Co. During the implementation of seismic survey operations, there were some difficulties due to the fact that a large part of the survey area was within the urban suburbs of Baghdad city. Traffic is very heavy in the area, and to further complicate matters, some seismic lines passed through an intensively farmed agricultural zone to the north – problems which still exist. As a result, some seismic surveys had to be repeated for detailed acquisition, and further work was carried out in the northern area to delineate the field’s extent.

The results indicated the presence of a number of faults, the most important of which trend north-west to south-east. The surveys indicated the existence of several structural closures and all the early drilling locations were based on these.

A simplified stratigraphy of the Cretaceous formations in the East Baghdad field.

The first well, East Baghdad-1 (EB-1), was drilled to test the Cretaceous and Jurassic reservoirs. Located about 20 km east of the center of Baghdad City, it was spudded in June 1975 and completed in May 1976, reaching TD at 4,842m in the Lower Jurassic Adaiyah Formation. Testing carried out after drilling indicated some hydrocarbon shows in the lower horizons, but did not give encouraging results. The deepest unit to produce oil was the Khasib reservoir, which produced around 2,830 bopd. A slightly lower production rate was later obtained from the Tanuma reservoir and a long oil column was found in the Hartha reservoir, but its productivity was small at around 630 bopd. The produced oil was around 24° API on average from these units. Oil shows were tested in the Lower Miocene Jeribe Formation and the Upper Cretaceous Sa’di Formation. Lighter oil was tested in the Lower Cretaceous Zubair Formation, but other potential Cretaceous reservoirs tested water.

East Baghdad-2 (EB-2) was located about 20 km south of EB-1. During drilling, oil shows were found from the reservoirs mentioned above, but the Tanuma and Khasib reservoirs were poor quality and production levels were worse than in EB-1. However, oil was also found in the Zubair reservoir, producing around 13,824 bpd of 38° API oil. Exploration continued and EB-3 was drilled in 1978 in the central urban part of East Baghdad, with the main objective being the Zubair reservoir.

In the short time period between 1979 and 1981 a further 22 wells were drilled, covering an area of about 60 km2. The first assessment and proposal for a development scheme was carried out between 1982 and 1983, when a geological model was prepared and an area for a Pilot Project to assess the performance of the different reservoirs was chosen, in preparation for a well-supported, phased development plan. The years 1983–1990 witnessed the delineation of the field to the north-west of the River Tigris, with a total of 85 wells. The drilling results showed a wide variation in the well rates with a range of 50 to 250 bopd recorded, due to field complexity and lithology changes.

The field needs further evaluation, particularly in the north-west, which will add a new phase of development to the existing scenarios.

Satellite image of Baghdad showing the location of Sadr City on the eastern edge, and the area depicted in the 1944 map (next in slideshow). (Source: NASA)

Baghdad in 1944. The Nadhim Pasha Dam can be seen running north-west – south-east and then due south in the top right quadrant of the map. (Source: University of Texas Libraries, The University of Texas at Austin)

Source Rocks, Maturation and Migration

Recent studies by Al-Ameri (2011) on the correlation between the oil from the Khasib and Tanuma reservoirs and the kerogen of the source rocks indicated the presence of mature source rocks in the uppermost Jurassic to lowermost Cretaceous (Tithonian-Berriasian) Chia Gara Formation, which consist of limestone and calcareous shales. The generation of petroleum in the Chia Gara Formation began in the Upper Cretaceous, and continued to the Lower Tertiary (Late Eocene) time. This coincides with the formation of the Khasib and Tanuma structural fold closures in the East Baghdad structure at the Cretaceous/Tertiary time boundary event.

The second phase of trap formation was a result of the abrupt change in thermal subsidence during the Miocene, which coincided with the Alpine orogeny. This event is responsible for terminating Tertiary oil migration. The generated and expelled hydrocarbons migrated along faults and compression joints in the anticline crest and charged the Upper Cretaceous Khasib Formation and Tanuma Formations. Spilled-out oil migrated upwards to the younger Lower Miocene reservoirs below the Upper Miocene Lower Fars regional seal.

There are no studies available on the source of the lighter oils in the Zubair reservoir.

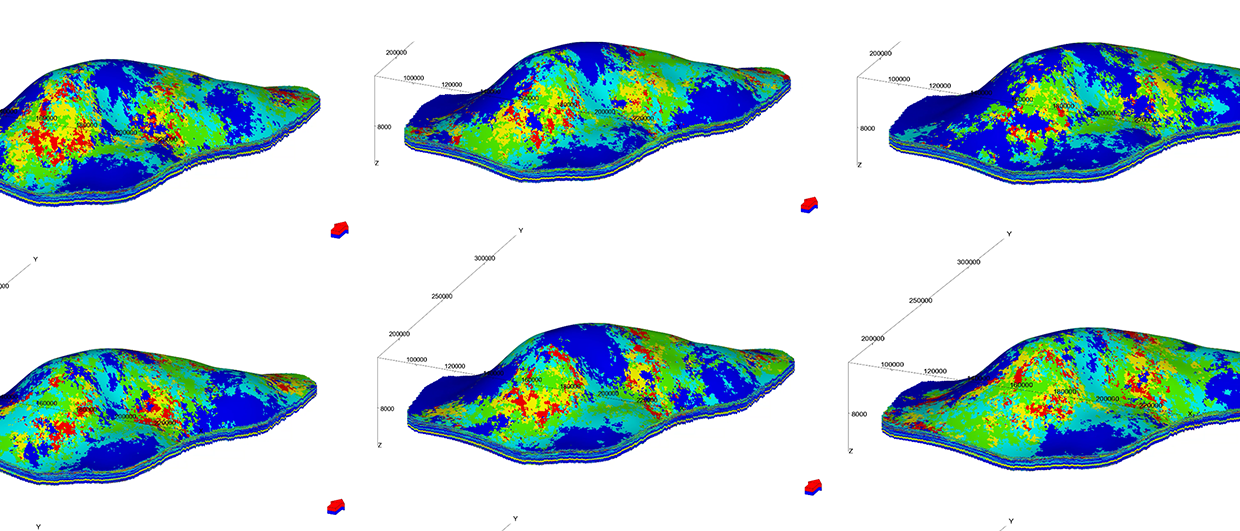

The East Baghdad field in relation to the city and also the suburb of Sadr City. The field is characterized by a complex structure, shown in red, which is connected to a central fault that extends along the field with transverse faults, resulting in a number of structural traps. (Munim Al Rawi /Mark Fitzpatrick/Bruce Winslade)

Cretaceous Reservoirs

The East Baghdad field extends for more than 100 km in a north-west to south-east direction, with a width of over 10 km in places. The field is characterized by a complex structure, which is connected to a central fault along the field, with transverse faults trapping oil. Oil production to-date has come mainly from the late Cretaceous Tanuma and fractured Khasib carbonates and from the early Cretaceous Zubair sandstone formation. Oil has been successfully tested in other Cretaceous reservoirs, including the Hartha carbonates, Mishrif/Rumaila carbonates, Nahr Umr clastics and Ratawi mixed clastics/carbonate, and there also have been good oil shows in other Cretaceous reservoirs. Overall, about 90% of the reserves are found in the Upper Cretaceous reservoirs and 10% in the Middle and Lower Cretaceous reservoirs.

Topographic map of Iraq, created from SRTM data. (Source: Sadalmelik)

The Upper Cretaceous Hartha, Khasib and Tanuma Formations consist of carbonate rocks with a chalky, variable nature, generally with high porosity and low permeability. In each of them the upper parts are more porous than the rest of the formation, while the middle parts are water-saturated. Average porosity and permeability are about 15–20% and 45 mD respectively. The Tanuma and Hartha Formations exhibit the same oil property variations from top to bottom throughout the reservoirs, whereas the Khasib reservoir shows a lot of variation in oil types over the formation as a result of compartmentalization due to transverse faults which trend almost perpendicular to the axial trend of the structure and which do not extend up into the younger horizons. Oil gravity ranges between 15° and 24° API, with an average of 20° API. The presence of a tar mat at the base of the Khasib reservoir may indicate the oil/ water contact.

The Middle Cretaceous Nahr Umr sandstone reservoir, which occurs mainly in the northern part of the field, has potential but it has not been produced as yet.

The Lower Cretaceous Zubair Formation consists of alternating clean sandstone and shale with good porosity and permeability values and high productivity, with an oil gravity range of 32°–38° API, averaging 34° API. However, analysis of the results of the drilled wells showed this reservoir to be less important than originally considered as the accumulations in the formation appear to be located in non-continuous lenticular sandstone units. The Hartha Formation does not reservoir oil over the whole field, but is limited to certain areas.

It would appear that the only continuous reservoirs are the Khasib and Tanuma units, which consequently became the main targets for development drilling.

Limited Production

“Baghdad, Iraq. Gigantic capital along the Tigris. Once the largest city on Earth, millions of us call this city home.” Caption by astronaut Chris Hadfield aboard the International Space Station. (Source: NASA/Chris Hadfield)

The East Baghdad field began production on April 1989 at an initial rate of 20,000 bopd and 14 MMcfgpd. Studies indicated that production would require pressure maintenance by water injection, as well as artificial lift in the producing wells, and gas lift was selected as the alternative option. Production stopped in both 1991 and 2003 due to conflict. Since 2009, the East Baghdad field has been producing 10,000 bopd of 20°–24° API from the Upper Cretaceous reservoirs, all of which is sent to the old Doura refinery in South Baghdad for local use.

Pre-2003 plans encompassed a phased development with an eventual plateau of 160,000–200,000 bopd in order to link development with utilization of the produced oil. The first phase of this development was to supply the central refinery, which was planned to have a capacity of 40,000 to 80,000 bopd, but was never constructed. However, during Iraq’s Second Petroleum Licensing Round in December 2009, the East Baghdad field was offered for development with a plateau production target of 30,000 bopd. The contract area for the offering was about 65 km long and 11 km wide, covering only the section of the East Baghdad field north-west of the Diyala river, but no bids were received.

Drilling Under a City?

View of Sadr City 2005. (Source: US American Forces Information Service)

The East Baghdad field oil and gas in-place reserves are reported to be 31 Bbo, with over 11.3 Tcf of associated gas, of which recoverable oil and gas reserves are 4.67 Bbo and 9.3 Tcfg. This makes it a super-giant field, but only a relatively small amount of it has been recovered so far.

The dilemma facing Iraq is how to exploit this resource without disturbing or endangering the multitudes who live and work above it. Since the East Baghdad field is situated within well-populated residential districts and a dense agricultural area, directional drilling was originally selected as the most appropriate way to drill most of the delineation wells. Some studies were also carried out to ensure population safety against any risk resulting from drilling and work-over operations.

It is suggested here, however, that the best way of fully developing this super-giant field may be by creating industrial zones between the residential suburbs of East Baghdad. Development of the field may also be a solution for the unemployment in the troubled East Baghdad districts. The high financial field development cost may well be a price worth paying.

References

Al-Ameri, T.A., 2011. Khasib and Tannuma oil sources, East Baghdad oil field, Iraq. Marine and Petroleum Geology, Vol. 28, Issue 4, p. 880 – 894, April 20111.

Ministry of Oil, 2009. Iraq’s Second Petroleum Licensing Round. Petroleum and Contracts Licensing Directorate. December 11, 2009, Baghdad, Iraq.

OAPEC 1987. Appraisal and development of East Baghdad field (an experiment to understand a complex field). In Addendum of Papers and Case Studies Presented at the Seminar on Petroleum Reservoirs, Kuwait 11-14 October 1987, p A36 – A47.

Uqaili, T., 2001. EAST BAGHDAD FIELD ASSESSMENT & DEVELOPMENT. In MENA 2001 Conference. Target Exploration Consultants, London, UK.