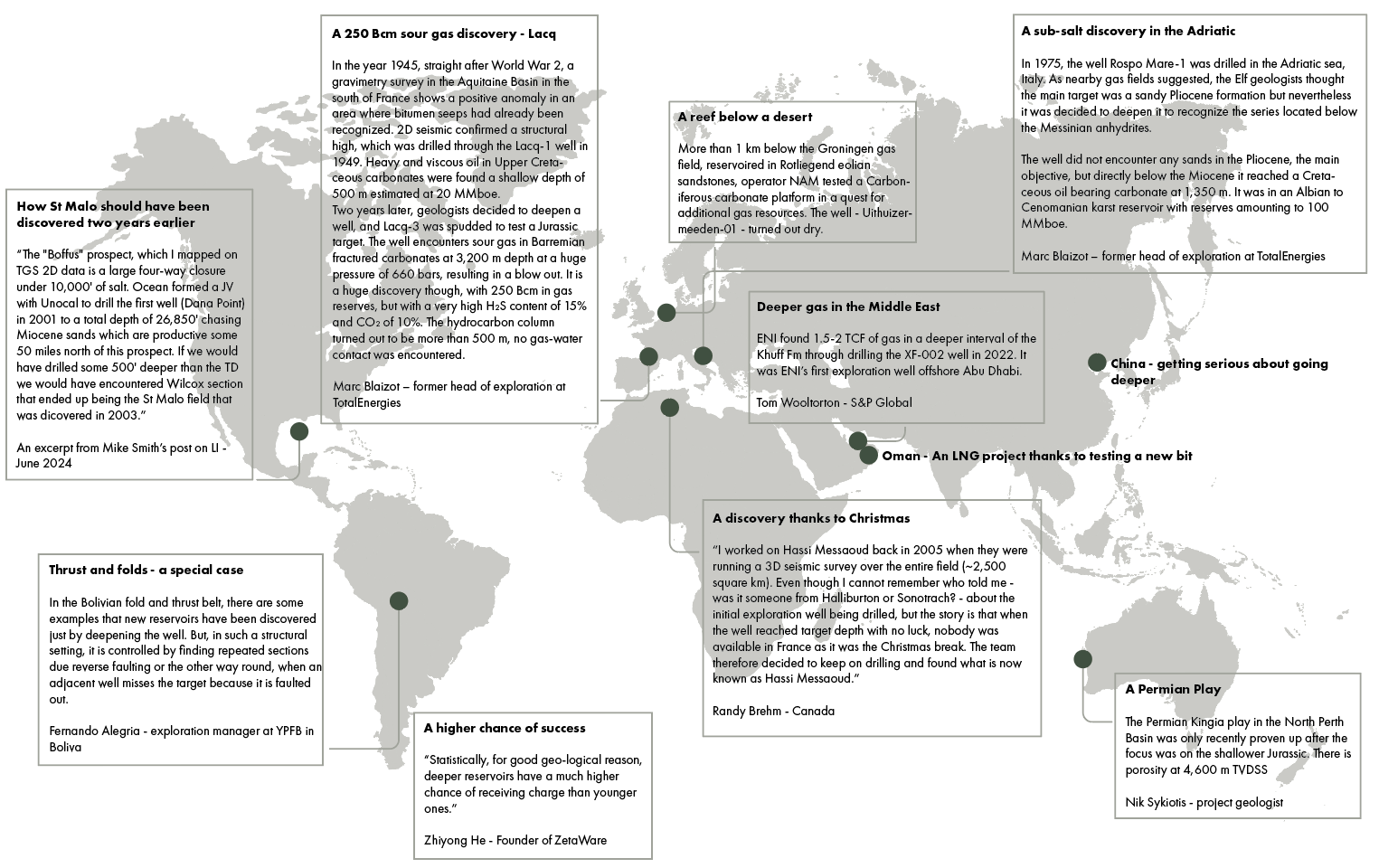

The idea for this story was born when I saw a LinkedIn post from Mike Smith in the USA in which he wrote about a well in the Gulf of Mexico that was drilled a little deeper than a previous exploration attempt very close by. It found the St Malo field. If only had the first well drilled a bit deeper.

Being such a good example of the benefit to drill a bit deeper than the primary target, I decided to put out a request on our LinkedIn page for more stories along these lines. And as always, there were quite a few good ones from all over the world.

Initially, based on the input I received, this story looked like going to be a series of serendipitous exploration successes. But then, I was made aware of an interesting project in China by Marc Blaizot – former global exploration manager at TotalEnergies. The Chinese seem to have made a real thing of going deeper and beyond “primary” targets, as we further describe in this article.

The China example is not an isolated case. In quite a few other places around the world, companies are chasing resources deeper than where the “first generation” of oil and gas reserves came or come from. It is a sign that the industry as a whole is moving towards finding and producing deeper, and more technically challenging resources.

Saudi Aramco developing tight gas beneath the Jurassic Ghawar field is a good example of this. Similarly, on a much more modest scale, the Permian Kingia Formation in the Perth Basin of Western Australia is also an example of a deeper stratigraphic interval that has more recently come on the radar. In other words, the industry is really testing what some people may have called “economic basement” a while ago. It reminded me of the observation Rodney Garrard made in his column for the magazine: “We are not moving away from hydrocarbons, hydrocarbons are moving away from us.”

So, in the end, this story is a mix of serendipitous finds – the best ones to tell about at the coffee machine – and the more “planned” campaigns. Altogether, a clear sign that going deeper can be called a new frontier.

The map below shows and tells the stories we sourced, with two longer stories on Oman and China below.

How testing a new drill bit ultimately resulted in a major LNG project

It would be great to attribute a spectacular gas discovery to the inquisitive and persistent nature of a person or a group of people working on the exploration campaign. But in the case of the Barik 1 well in Central Oman, the well that kickstarted what was to become the country’s only LNG project, nobody can make that claim. When Barik 1 was drilled in 1991, TD was called at around 4,500 m without encountering a sniff of hydrocarbons.

The idea of the well was to drill the first of a series of deep-seated domes in the Ghaba Salt Basin that were mapped on seismic lines before. The target reservoirs were initially supposed to be of Mesozoic age, in analogy to the already known time-equivalent carbonates and siliciclastic reservoirs from the northern part of Oman. When the bit had clearly started drilling onto the Paleozoic without encountering any hydrocarbons, it was therefore decided to abandon the well.

“It was during the morning brief that we heard that the driller had however sought permission to drill a little further to test a new bit”, says Meindert de Ruiter when I speak to him over the phone. Meindert was the Team Lead for Central Oman at PDO at the time, and was part of most routine meetings that took place discussing drilling progress. “We did not expect any issues doing so, so the driller was given the goahead”, says Meindert.

“But when I came back from our lunch breaks – in Oman we enjoyed lunch at home in those years – the excitement in the office was great. Only a few meters below the level where we had planned to call TD, the gas readings went all over the place.”

Rather than finding gas in Mesozoic rocks, the bit had proven the Ordovician Barik sandstone instead.

“Reservoir properties of the sands at the well were not great” remembers Meindert, “but it is gas so you do not need great permeabilities to make the reservoir work.”

The Barik-1 well had thus kickstarted the development of what soon became to be a new cluster of fields that would justify the construction of what still is Oman’s one and only LNG facility that operates three trains at Qalhat.

China – getting serious about going deeper

CNOOC recently issued a press release discussing the results of the first ultra-deep well (Bozhong 19-6 Condensate Gas Field D1 Well) completed in the Bohai Bay area, offshore China. This is interesting from multiple points of view.

First, it gives away what China is focusing on in the light of their recent announcement to set up a special company dedicated at drilling deeper wells. The press release fits into this, and suggests that China is not only looking to find deep gas in onshore basins like the Tarim, but is also looking at finding hydrocarbons beneath existing assets.

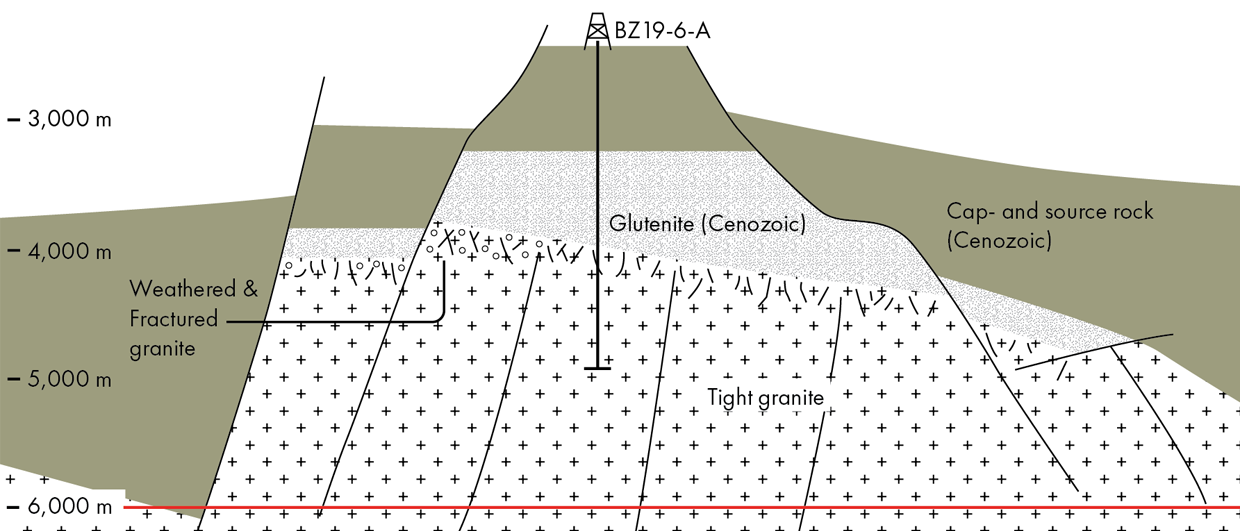

Secondly, the reported terminal depth of the well at more than 6,000 m is worth noting. This depth is indicated as a red line in the cross-section shown here. The section shows the Bozhong 19-6 condensate field and was adapted from a publication by Mingcai Hou and co-authors. The exact location of the newly drilled well is unknown, but if this section is anything to go by, it suggests that the company drilled either into fresh unweathered basement or very deeply buried clastics on its sides. This poses the question; how can flow rates of 6,300 barrels of oil equivalent per day be achieved in such a subsurface setting?

We received some interesting feedback on our post we did when CNOOC had just published the press release.

Tako Koning, an experienced petroleum geologist who worked in fractured basement reservoirs during his long career, argues that looking at possible analogues for this discovery is useful. He wrote: “For example, the oil column in the Bach Ho oil field, Vietnam, is 1,500 m, entirely in fractured Precambrian granite. Buried hill basement oil fields in Chad also have such thick oil columns in fractured Precambrian granites. Another analogue is the Suban gas field, South Sumatra which has a 1,250 meter gas column in fractured Pre-Tertiary granites. The point being, depending on the intensity of the regional and local tectonics, the fractures in basement can extend down to great depths.”

Eleanor Oldham from Merlin Energy noted: “I’ve worked with some fractured basement fields so this piqued my interest and led to a quick Google search. I found a paper which does indeed suggest that CNOOC identified a secondary target of fractured reservoir below the primary weathered layer. These two reservoir zones are depicted as separated by a tight interval.My assumption would be that this recent well was successful at discovering pay in the deeper, secondary target. Although, I admit there are currently not enough details to back-up this assertion.”

It is worth following what the Chinese are doing when it comes to drilling deeper. They seem to be exploring subsurface domains that are not being considered by many others.