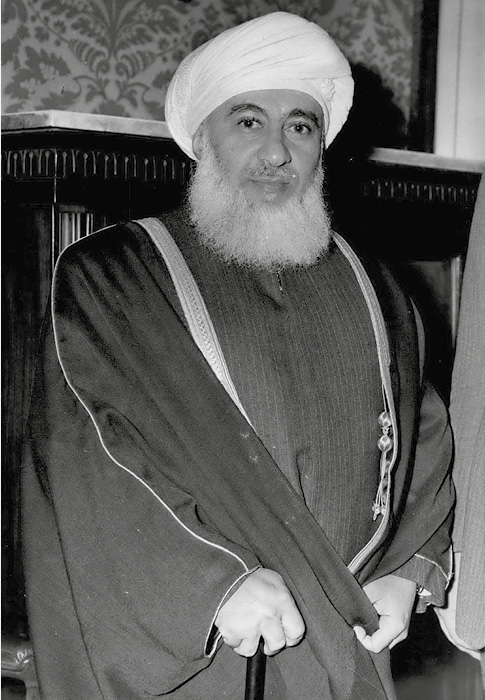

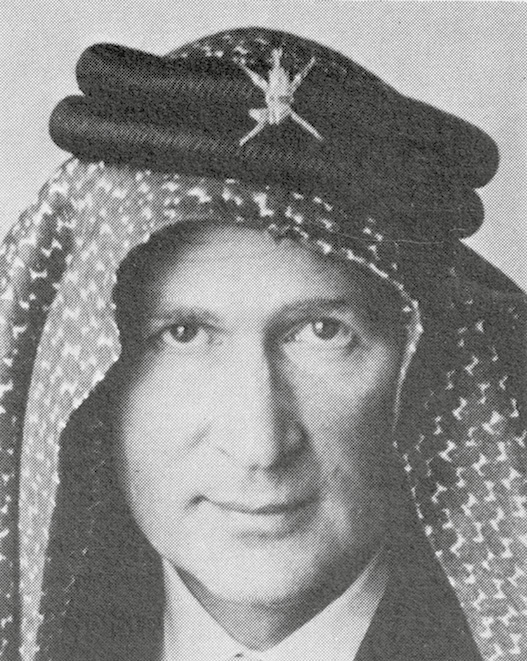

Wendell Phillips in Arab headdress in 1966 – he was also an honorary sheikh of the Bal-Harith tribe of Yemen. Credit: Illustrated London News.The 20th century American explorer Dr Wendell Phillips is best known for his colorful exploits in archaeology, which included surveys in Africa and Arabia, and for his work with the American Foundation for the Study of Man, which he formed in 1949. He was also an independent oilman who broke into the Middle East at a time when it was dominated by the major international oil companies. His subsequent career in the oil business was filled with tangled interests and mixed fortunes, but it was also remarkable for the fact that the impecunious archaeologist ended up as an oil magnate in his own right.

Wendell Phillips in Arab headdress in 1966 – he was also an honorary sheikh of the Bal-Harith tribe of Yemen. Credit: Illustrated London News.The 20th century American explorer Dr Wendell Phillips is best known for his colorful exploits in archaeology, which included surveys in Africa and Arabia, and for his work with the American Foundation for the Study of Man, which he formed in 1949. He was also an independent oilman who broke into the Middle East at a time when it was dominated by the major international oil companies. His subsequent career in the oil business was filled with tangled interests and mixed fortunes, but it was also remarkable for the fact that the impecunious archaeologist ended up as an oil magnate in his own right.

A Lucky Break

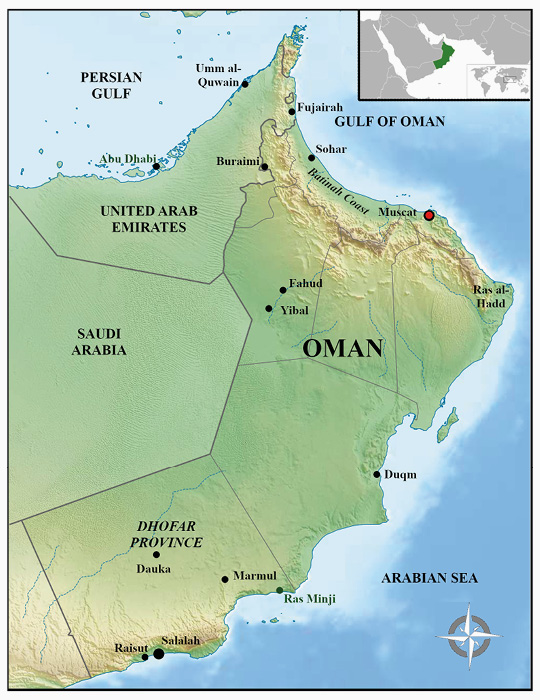

Even though Wendell Phillips was a lean man of medium height, he seemed to tower above the desert ruins in his Arab headdress with two pearl-handled pistols strapped to his waist. Among his many talents, he was an oilman, though his entry into that field was a lucky break. In 1952, he fled from Yemen after a disagreement with the authorities over an archaeological site at Marib, reputedly the palace of the legendary Queen of Sheba. He found refuge in the neighboring province of Dhofar, ruled by the sultan of Oman, Said bin Taimur. After befriending the sultan, Phillips began exploring the country for antiquities. But then, quite unexpectedly, he found himself the proud owner of an oil concession the size of Indiana.

He was an unlikely figure for this kind of adventure. Born to a poor family in Oakland, California in 1921, his mother was a gold prospector and wall-of-death rider, and he worked in various jobs as a youth, as well as suffering from polio, which he eventually recovered from. He attended the University of California at Berkeley, although his studies were interrupted by wartime duties in the Merchant Marine before he returned to college to obtain a Bachelor of Arts in paleontology. He joined in fossil-hunting expeditions to Arizona, Oregon, and Utah, but it was his powers of persuasion that won the funding for his first archaeological expedition to Africa.

The Dhofar oil concession came as a complete surprise. Phillips had no experience of the oil business and his main interest was archaeology. But perhaps the sultan saw something in this enthusiastic young man that suited him to the task, an ability to get things done. Over the next few days, Phillips hammered out an oil-concession agreement and then set about arranging finance, though the obstacles were formidable. Dhofar was ‘remote from American thinking’, and there were no port facilities, so that all equipment would have to be flown or floated in. Undaunted, he pressed on with his plans. In January 1953, the concession was assigned to a newly-formed company, Dhofar-Cities Service Petroleum. Phillips, taking a leaf out of the oil magnate Gulbenkian’s book, retained a two-anda-half percent royalty share.

In his early 30s at this time, Phillips was set for a stellar but often controversial career in the oil business. “To businessmen, he was a scholar, to scholars he was a showman,” wrote Herbert Solow in Fortune magazine. Others were more flattering – Lowell Thomas, the American writer, made the comparison with Lawrence of Arabia. The oil companies looked on begrudgingly when he pulled off his latest business coup. This would be a recurring theme in his career: the maverick against the establishment. Not that Phillips was fazed – he never claimed to be an oilman, preferring to be called an explorer. “With me, oil is a hobby that happens to pay,” he once said.

A Pyrrhic Victory

The sultan’s enthusiasm for a loner in the petroleum world is partly explained by the fact that, until then, oil exploration had been controlled by the British-led Iraq Petroleum Company, a consortium of major international oil companies, which had just surrendered its concession for Dhofar. The British authorities, who exercised considerable influence in Oman, were nevertheless concerned by Phillips’ involvement because he represented American interests in an area where British interests held sway; and his activities also threatened to aggravate Oman’s border problem with Saudi Arabia. Phillips’ answer was to accompany the wali of Dhofar on an expedition to a disputed area of the desert to plant a territorial marker there, then to add his own name to it.

Dhofar-Cities Service set up their headquarters in a palm grove near a beach at Raisut to the west of Salalah, and a number of aerial surveys were flown over the territory. Dhofar had a three-month monsoon season known as the khareef which started in late spring and covered the coast in a thick fog, causing aircraft to fly out to sea and then descend to wave-top level before turning back towards the RAF airstrip. The sultan built a 50-kilometer road from Salalah into the Qara Mountains for huge Kenilworth trucks to transport collapsible derricks into the desert interior. Exploration camps sprang up overnight, and millions of dollars were spent.

On April 15, 1955, Dhofar-Cities Service spudded-in their first test-well at Dauka, followed by two wells at Marmul in 1957 and 1958. The oilmen were expecting to strike oil, and did so at Marmul. However, their hopes were soon dashed when the oil flow declined on testing; it was a time of oil glut and low prices which made the heavy oil (22° API and 40–200 cP viscosity) at Marmul unprofitable. In 1962, the company assigned its interest to John Mecom and Pure Oil. In 1967, after more changes, with $40 to $50 million spent and 29 wells sunk, the Americans withdrew. They had found oil but at great cost and with no commercial advantage. When all was said and done, it was a pyrrhic victory, although Phillips had already sold part of his share for $1 million by then.

The World Beckons

In April 1955, Phillips established contact with the Libyan government and ruling family, and obtained an exploration permit for the Cyrenaica area. But there was a problem – he needed the authority of the elderly and infirm King Idris to proceed, and the king would not see Phillips alone, but only as a member of a delegation. Undeterred, Phillips visited the king’s palace at Tobruk on the coattails of an American delegation led by Harold E. Talbott, the secretary of the US Air Force. Forced to wait outside the royal chamber while the delegation went inside, Phillips slipped in as soon as the meeting was over. He talked to the king about archaeology, which was enough to secure a second interview to talk about oil.

The prospect of having an independent oil company operating in Libya appealed to the king, much as it had to the sultan of Oman. Repeating the tactics he used in Dhofar, Phillips turned over his exploration permit for Cyrenaica to a US oil company, the newly-formed Libyan American Oil Company, and retained a three percent royalty on future production. There followed an awkward period in which allegations were made against Talbott and Phillips – the gist being that they were ‘thick in Libya’ – but the Petroleum Commission decided in the company’s favor, operations proceeded and Phillips’ royalty share was intact.

He was never one to rest on his laurels. Oil ventures were calling from the rain forests of Venezuela, and from Africa and South East Asia. There were persistent reports that he was dabbling in the Trucial States (today’s United Arab Emirates): in 1966 he made an offer to the sheikh of Fujairah for an offshore concession, and in 1969 he assembled a group of business interests to apply to the sheikh of Umm al-Quwain for an offshore concession in the Persian Gulf. And there was Australia: in 1968, it was reported that he had turned his attention to the Land Down Under. All these activities were coordinated from his home in Honolulu.

A bachelor till the age of 47, he married an 18-year-old local girl, but the marriage did not last. “She just could not adjust to my way of life,” he told the press, alluding to his globe-trotting activities. By then he had 18 honorary degrees from universities around the world. “I am first and foremost an explorer and archaeologist. My second objective is to publish my findings. I’m getting close to that goal despite all the money that’s come along,” he told the New York Times.

A Comedy of Errors

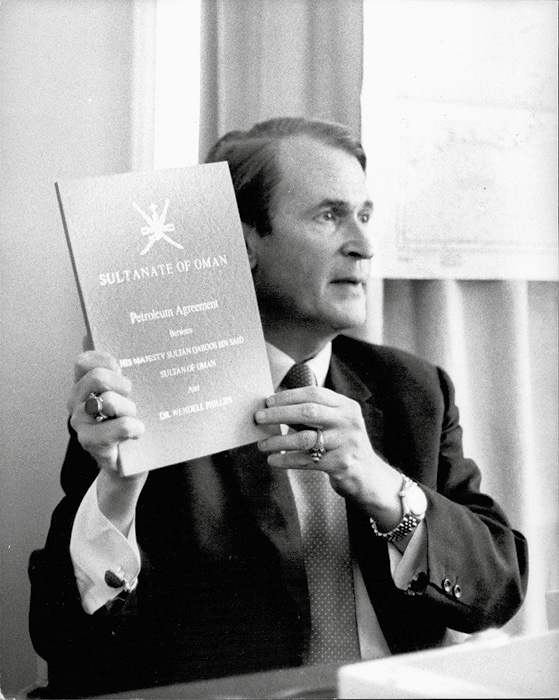

His first love remained Oman. He wrote two books about the country and remained on good terms with the sultan, describing himself as his ‘economic adviser’. In the 1950s, there was talk of an oil concession for the sultan’s territory of Gwadar (now part of Pakistan). In December 1965, it was reported that the sultan had granted his company, Wendell Phillips Oil, an offshore concession stretching from the Batinah Coast to Ras al-Hadd, which he had assigned to a German firm, Wintershall Aktiengesellschaft. But in July 1970, his old friend Sultan Said bin Taimur was replaced in a bloodless palace coup by his son, Qaboos. This was followed in March 1971 with news that the new sultan had awarded his company a new offshore concession for the southern coast of Oman, stretching 450 miles from Ras al-Hadd to Ras Minji near the border of Dhofar province. In true style, a breathless Phillips announced the news to a press conference in London and waved a signed agreement in the air – it was a document handsomely bound in red leather with gold lettering. What could possibly go wrong?

At this point, the story takes a curious turn. Following the coup, the decision about Phillips’ concession rested with Sultan Qaboos. There was confusion about what exactly had been granted: was it a concession, option, contract, commission to study, or something else? The sultan couldn’t remember the details and in August 1971, Phillips’ representative arrived in Muscat to make a down payment on the agreement only for his check to be written off as a ‘dud’. In September it was announced that the concession had been cancelled because Phillips had not arrived in Oman to sign the documents. “No visa was sent to allow me to come to Muscat,” he protested. To cap the whole comedy, word was received that his visa had been cancelled – even though he had never had one in the first place. Phillips lost the concession and was left to lick his wounds.

Wendell of Arabia

Wendell Phillips passed away in 1975 after a heart attack at the relatively young age of 54. He was a very rich man, reputedly with a fortune of over $130 million when he died, and some 40 producing oil wells and oil rights to 100,000 square miles of ocean to his name. The impression remains of a flamboyant showman and opportunist who achieved many remarkable things. In the oil business, he ruffled feathers as he went, although his singular skill in bringing together business interests in pursuit of his oil ventures shone through. “When opportunity came, I was not the odd man out,” he once said. His start in the oil business was a lucky break, but it was all his own efforts after that. And, if we imagine the pistol-strapped explorer emerging from the desert in Arab dress, for a moment we might think a comparison with Lawrence of Arabia was not so fanciful after all. But then, the irrepressible Phillips would have added: “I’m better than Lawrence.”

Thanks to Peter Morton and Alan Heward for their kind assistance.