“I have concluded that this area should not be explored for oil, but for hydrogen instead. And I believe that the potential is colossal,” wrote Marcello Rebora in his email.

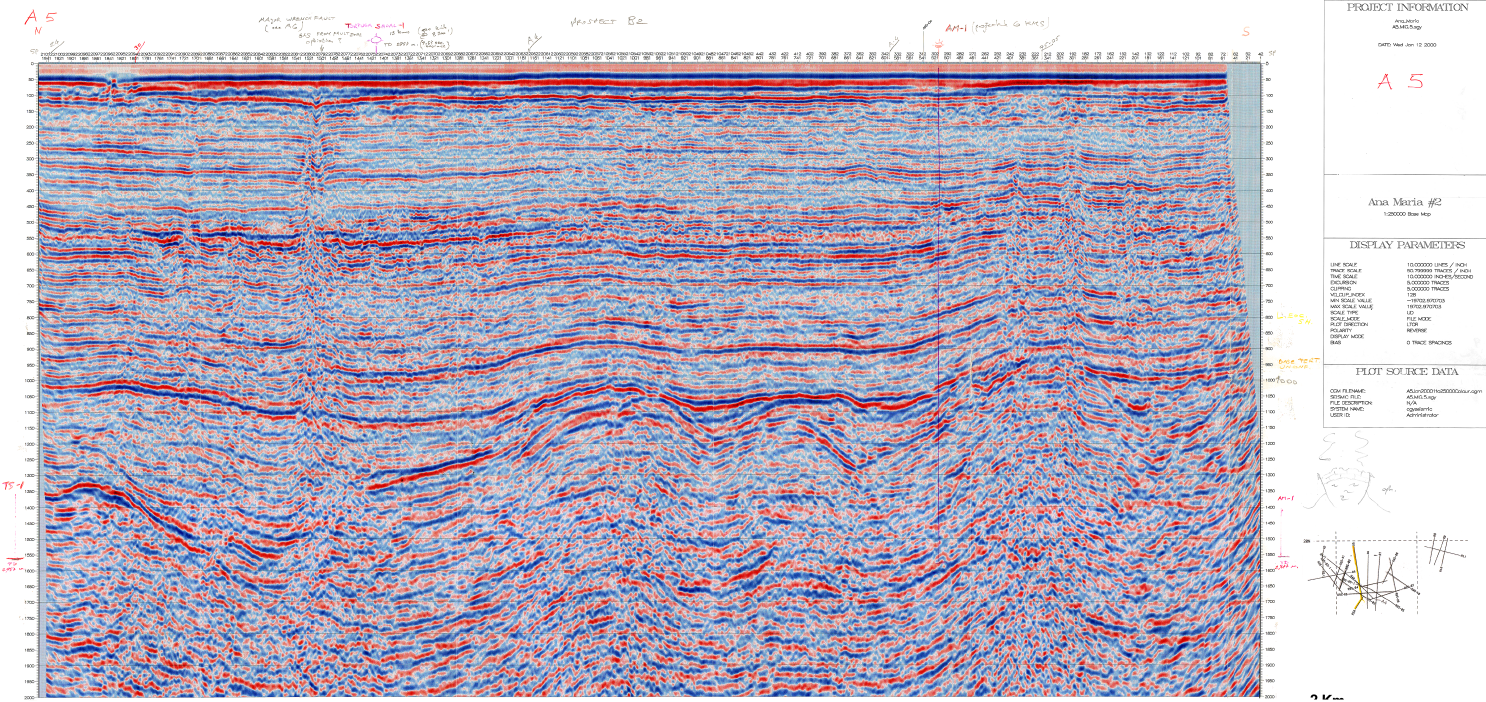

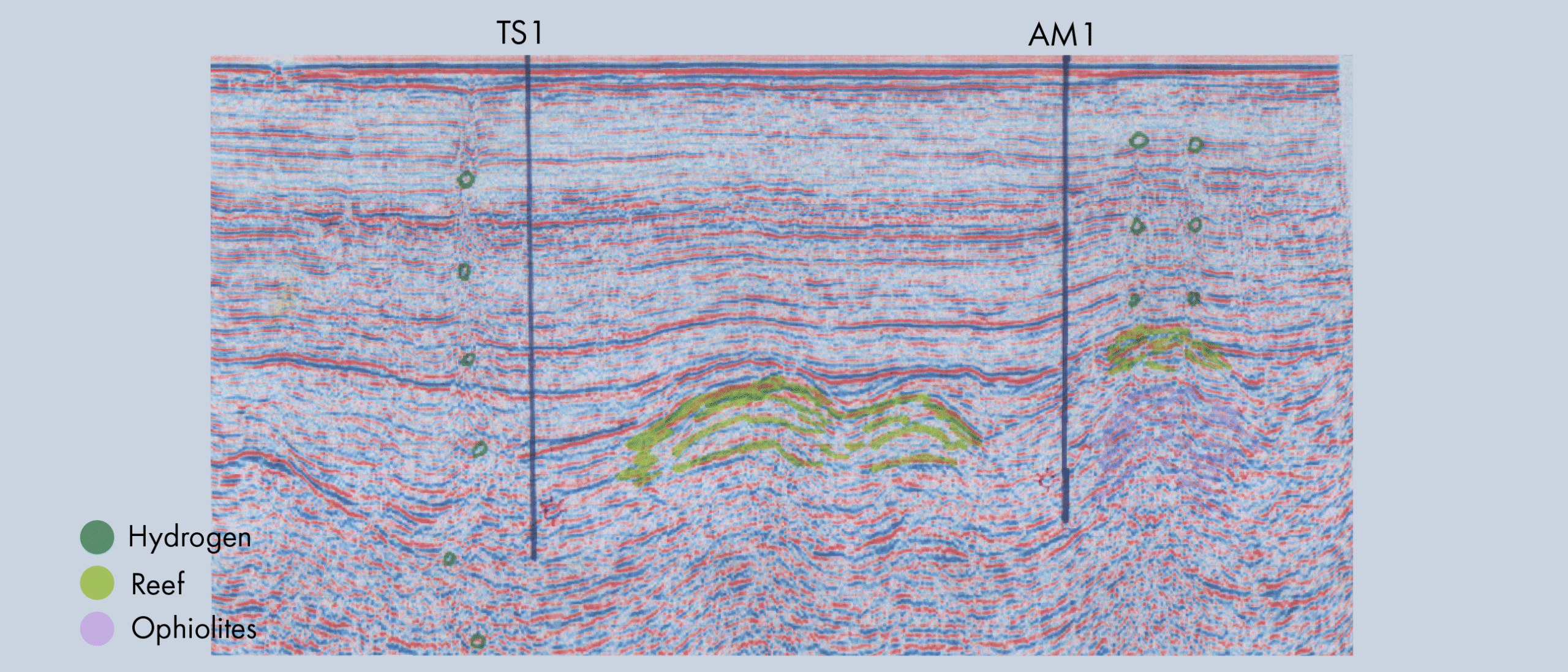

In the nineties, Marcello was involved in hydrocarbon exploration offshore southern Cuba. More recently, he started to look at the data again, out of curiosity. His review of seismic, well, gravity, geological and geochemical data in the Golfo de Ana Maria and Guacanayabo, where his company held licences at the time, led him to conclude that the area has potential to make a commercial hydrogen find.

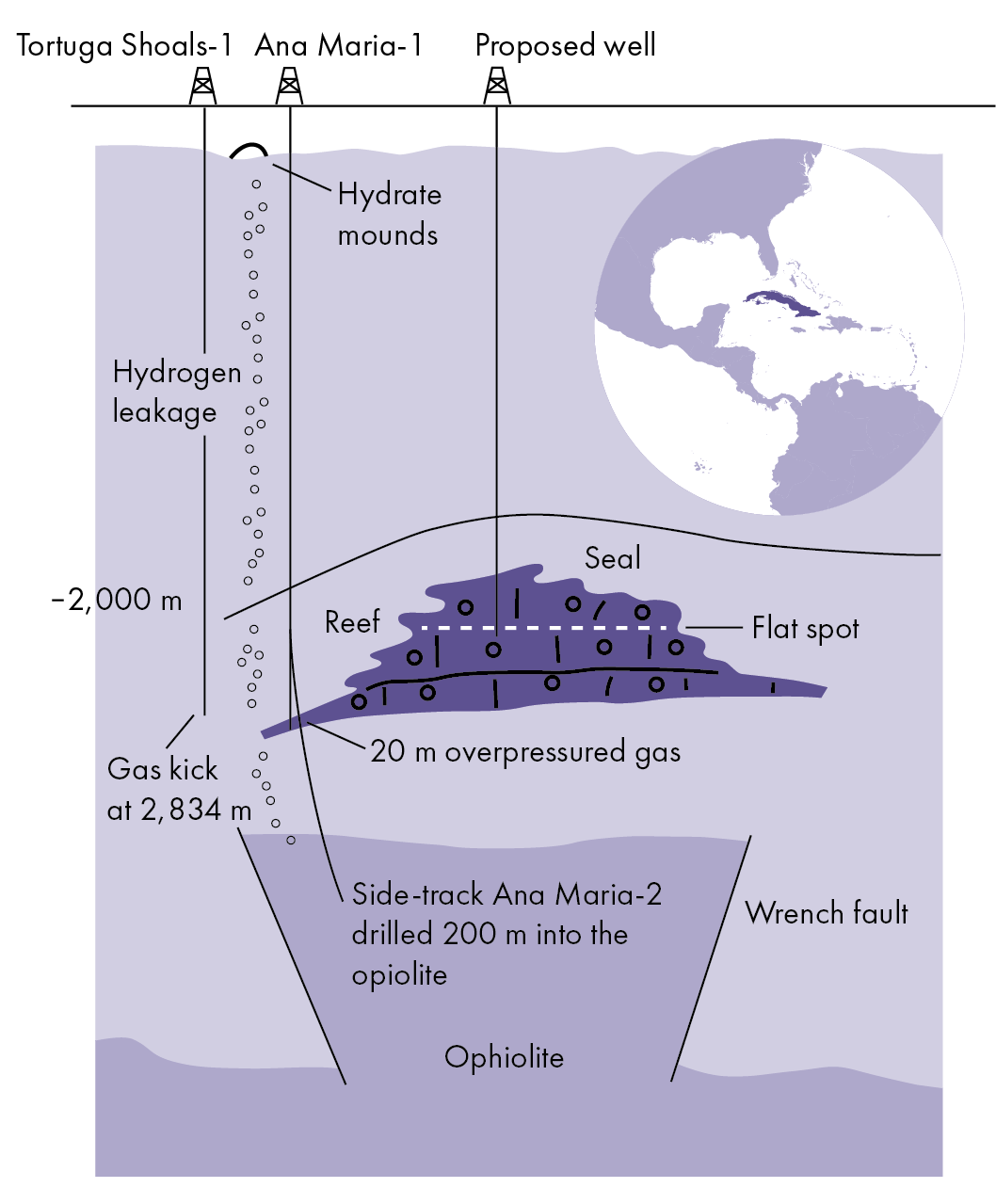

“There is an ophiolite at a convenient depth, there are basement faults acting as conduits, there are porous reservoirs and there is a proven sealing unit. All the ingredients needed for a successful natural hydrogen play,” wrote Marcello. “And this is further supported by surface seeps.”

Here is a short summary of how Marcello came to this conclusion.

Clipping reefs

“In 1996, our group drilled the well Ana Maria-1 from an island some 1.5 km from the nearest marine seismic control, practically as a stratigraphic test. It ended up being drilled downdip from a cluster of Upper Cretaceous reefs,” writes Marcello.

“The well found a limestone section deposited in a basinal and talus position, containing debris from an adjacent rudist reef. Some of the limestone samples were replaced by dolomites containing sphalerite and uranium, deposited from hot fluids derived from the underlying ophiolites.”

The limestone section in the well consisted of 20 m of overpressured gas, which suggests a good seal.

“At that time, the rig didn’t have the equipment to prove the presence of hydrogen,” adds Marcello, “but with the overpressured section being about 800 m deeper than the adjacent reefal structure that shows a flat spot, the obvious conclusion is that it is full of gas.”

Years before this, the well Tortuga Shoals-1, drilled by Stanolind and also based on limited seismic control, did not reach the reef either, but also contained rudistic debris in the samples and had a gas kick at 9,300 ft.

The obvious follow-up well to drill the reef properly, which was named Bajo Corales-1, was never drilled as investment was diverted elsewhere at the time.

What needs to be done now

Combined with the results of a gravimetric survey that points to an uplifted basement core beneath the reefal structure that was clipped by the Ana Maria-1 well, Marcello now argues that all that needs to be done is to drill the crest of the reef with a new well and test the gas. “If my interpretation proves correct, it could not only revolutionise Cuba’s economy, but it could represent the beginning of the replacement of oil as a source of energy,” he concludes.