Neogene-Quaternary volcanic rocks, atop or around sedimentary basins, cover an extensive tract of the Central Anatolian Plateau. These rocks in concert with faults, water and wind have created lofty summits, valleys, hot springs, a picturesque landscape, as well as cave houses and temples for several civilisations inhabiting this region known as Cappadocia. This is one of Turkey’s most fascinating areas for tourists, historians, archaeologists, and geologists.

Turkey: tectonic crossroads

The country of Turkey (historically known as Asia Minor and Anatolia) sits on a tectonic crossroads of colliding plates and active faults, and presents a fascinating geology for investigation.

The country is essentially a high plateau surrounded by the orogenic belts of the Pontides to the north and the Taurides to the south. Throughout the Cenozoic, Anatolia has been a region of head-on convergence between the Afro-Arabian plate to the south and the Eurasian plate to the north. The subduction of the Neo-Tethys Ocean located between these two plates during Eocene-Miocene times was followed by continental collision, mountain uplift, and deformational structures including folds and thrusts, strike-slip faulting, and extensional tectonics. The name “Tethys” (whose basins account for 70% of the world’s proven oil reserves) should make Turkey an appealing country for oil exploration, but active tectonics and high mountain uplift has complicated (and in places obliterated) its potential petroleum geology. Ocean-floor subduction along the continental margin is presently taking place in the Mediterranean Sea while tectonic stresses have produced an earthquake country criss-crossed by active faults.

Cappadocia volcanic country

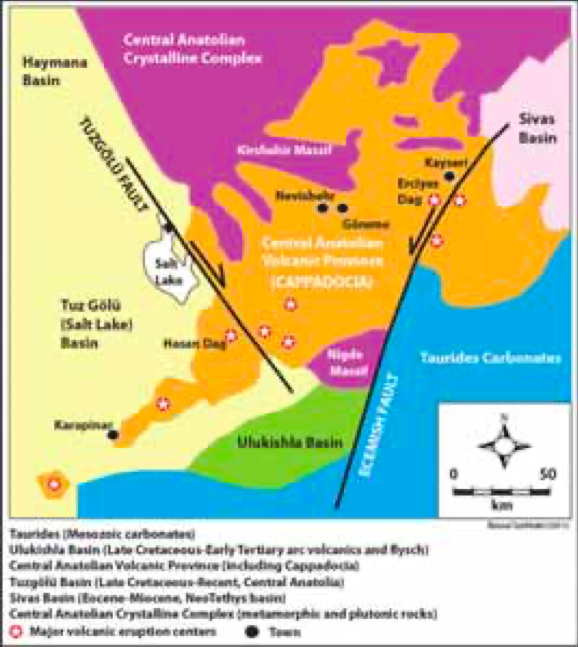

A remarkable feature of Turkey’s geologic landscape is several clusters of Middle Miocene to Quaternary volcanic rocks (14-0 Ma), including those in the Central Anatolia Plateau where Cappadocia is located. The region is about 300 km long and spans from the town of Kayseri in the east to Karapinar in the south-west, oriented in a north-east – south-west direction. Cappadocia is at a mean elevation of 1,050m, and covered with volcanic or volcaniclastic rocks.

This volcanic terrain is surrounded by and superimposed upon sedimentary basins of Cretaceous-Cenozoic age. However, the hydrocarbon prospectivity of these basins and the thermal effect of volcanic activity on the sedimentary rocks have been little explored or quantified.

The origin of the post-collision volcanism in Cappadocia has been debated for a long time, but geochemical data indicate that it is calc-alkaline arc volcanism (for example, the study by Pinar Sena and her colleagues reported in Geological Magazine, 2004). It was probably generated from a lithosphere mantle source, a residual of the previous ocean-floor subduction between Afro-Arabian and Eurasian plates, which later erupted due to crustal extension and normal faulting in the upper plate.

Major strike-slip and extensional faults both surround and occur within Cappadocia. Mapping by geologists such as Vedat Toprak of Middle East Technical University in Ankara has shown that two fault systems dominate Cappadocia: (1) The strike-slip faults of Tuzgolü (right-lateral) and Ecemish (left-lateral) bounding the volcanic province and other smaller faults within the region but parallel to these two major structures: and (2) a series of faults trending N60-70°E along the axis of volcanic terrain. Major eruptive centres in Cappadocia are located close to or at the intersections of these fault systems, and are thus tectonically controlled. The volcanic rocks in Cappadocia come in various forms, including:

Volcanic Complexes: These are circular to ellipsoidal features, 5-40 km in diameter, and correspond to major eruptive centres. Nineteen volcanic complexes have been mapped and named after the provinces in which they occur. The volcanic complexes form lofty mountain summits (“dâg” in Turkish) such as Erciyes Dâg (3,917m, the highest and home to a popular ski resort) and Hasan Dâg (3,253m). The majority of these volcanic complexes are stratovolcanoes (composed of several volcanic strata) made up of basalt and andesite.

Cinder Cones: A cinder cone is a conical hill of volcanic glass fragments (cinders or scoria) and lava flows that surround a volcanic vent. Cinder cones usually occur on the flanks of volcanic complexes. More than 500 cinder cones have been mapped in Cappadocia.

Fairy Chimneys: These are Cappadocia’s most attractive features. The result of particular erosion of ignimbrites (pumiceous pyroclasitc deposits), they come in various shapes such as column, mushrooms and cones.

Volcaniclasitc Rock: A sequence of volcanic rocks intercalated with lake or river sediments cover a vast tract of Cappadocia and fill its depression. These volcaniclastic sediments have been named the Ürgüp Formation, deposited over the past 14 million years or so.

Civilisation after civilisation

The name “Cappadocia” (pronounced Kapadokia) is a mystery. We do not exactly know what language this word originally comes from and what it means. Many sources mention that it is an Old Persian word, Katputka, meaning “the Land of Beautiful Horses,” obviously in reference to the long tradition of raising fine horse in this part of Anatolia. The earliest record of the word is from inscriptions of the Persian kings (Achaemenid Dynasty) in the early sixth century B.C., when Anatolia was part of their empire.

The Central Anatolian Plateau was once largely covered by great lakes, which dried up and the present Tuz Golü (Salt Lake) is a remnant. Human settlement in Cappadocia goes back to a Neolithic (“new-stone age”) and Kalkolithic (“copper age”) culture, spanning 9,000-5,000 years ago. Obsidian stone tools and Mother Goddess figures have remained from these ancient cultures. The kingdom of the Hittites ruled the region from 1800 to 1200 B.C. and the Persians took over Anatolia in about 550 B.C. Interestingly, when Alexander the Great defeated the Persian Achaemneid Dynasty in 330 B.C., the Cappadocians put up a severe resistance against the Greek army, and thus remained under a Persian governance, called the Cappadocian Kingdom, until 17 B.C. when it fell to the hands of the Roman Empire with the city of Kayseri (“Caeserea”) as the capital of Cappadocia.

The region became a refuge for early Christians and, especially during the Byzantine Kingdom, from the 4th through to the 11th centuries, Christianity flourished in Cappadocia where remnants of many churches in volcanic caves can be seen today. In the 12th century, the Muslim Turks invaded and took over Anatolia.

In this way, various civilisations and ethnicities have shaped the cultural history of Cappadocia. This region was also part of the ancient Silk Road from China to Europe.

A visit to Cappadocia

Cappadocia has a semi-arid continental climate, with little rainfall, dry hot summers and cold snowy winters. Kayseri is accessible by flights from Istanbul, Ankara and Izmir. There are also trains and bus services from Turkey’s major cities to Kayseri and Nevishehr in Cappadocia. A bus ride not only costs less but also provides an opportunity to view the landscape.

One can easily spend weeks in Cappadocia as there are so many sites to visit. For a short stay and yet a comprehensive view of what Cappadocia typically offers, the town of Göreme offers the best and most popular option. The town, literally built in volcanic caves and fairy chimneys, has numerous hotels and an open-air museum and is registered as a World Heritage site by UNESCO. If you intend to visit the Byzantine churches in Cappadocia with some knowledge in advance, the books Caves of God: Cappadocia and Its Churches by Spiro Kostof (1989) and Kingdom of Snow: Roman Rule and Greek Culture in Cappadocia by Raymond Van Dam (2002) offer excellent sources of information. And for a fascinating bird’s-eye view of amazing Cappadocia take an early morning hot-air balloon flights.