Africa’s continental oil and gas game flourished on long-term trend from the 1970s onwards, bar some cyclical down-shifts. 2008 was one such crisis, as the world financial meltdown impacted all, and, more significantly so far, 2014-15, as crude prices halved and most companies plus governments encountered fierce headwinds.

In the last decade-plus, Africa’s governments, with few exceptions, indulged in a flurry of ill-advised resource nationalism initiatives. Many countries now find their E&P landscapes, structures, fiscal terms, investor contracts, capital tax levies and tax/subsidy regimes out-of-sync with crude cyclical realities that may yet last for several more years.

Crude Realities

Africa’s E&P world today faces a plethora of problems. These include low crude prices, squeezed operating margins, companies in stress, some corporate takeovers and failures, survival issues for many independents and most minnows, constraints on new equity raisings, need for portfolio slimming, excess supply and fewer buyers in farm-out markets, large project delays and venture cancellations, asset and corporate divestments, lesser FDI inflows, and lower upstream capex commitments. There are difficulties to market old or new open acreage and retain global oil investors, tougher competition from the rest of the world, especially Iran, Latin America and Asia, with a shift in portfolio realignment towards the less risky onshore and shelf, leaving richer deepwater prospects fewer or untended, as well as stalling shale gas/oil developments.

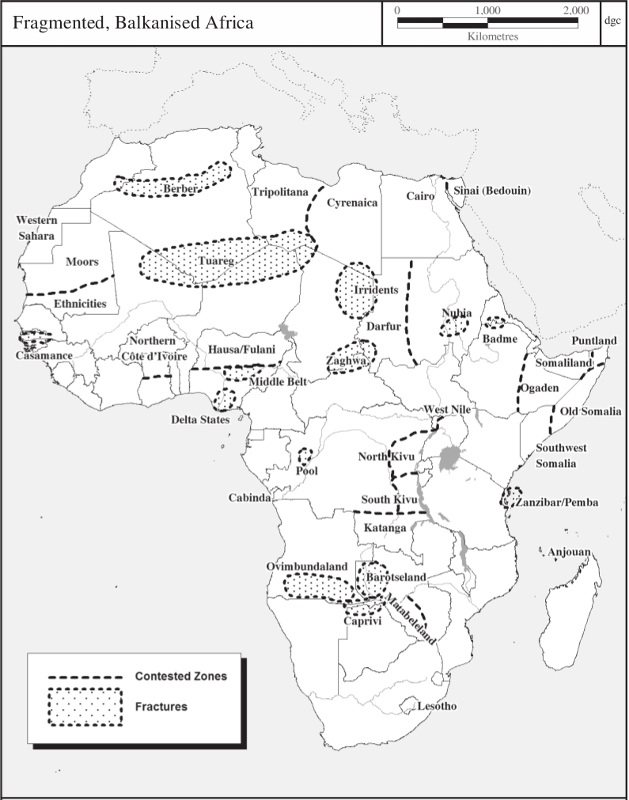

Multiple zones within and around Africa’s nation-state boundaries reflect social fractures and potentially balkanising entities, some with long histories of irredentism, others seeking autonomy, with separatists established out of the remnants of failing or failed states. The potential for fragmentation remains significant; the nation-states only recently constructed on top of old socio-economic realities. (Source: From ‘Africa’s Future: Darkness to Destiny’, Duncan Clarke)Many governments remain stuck in old ideologies unsuited to market conditions, aligned to the past milieu of high crude oil prices and once-easier upstream markets for seeking and retaining corporate oil players.

Multiple zones within and around Africa’s nation-state boundaries reflect social fractures and potentially balkanising entities, some with long histories of irredentism, others seeking autonomy, with separatists established out of the remnants of failing or failed states. The potential for fragmentation remains significant; the nation-states only recently constructed on top of old socio-economic realities. (Source: From ‘Africa’s Future: Darkness to Destiny’, Duncan Clarke)Many governments remain stuck in old ideologies unsuited to market conditions, aligned to the past milieu of high crude oil prices and once-easier upstream markets for seeking and retaining corporate oil players.

In the state-controlled oil world and for Africa’s national oil companies, multiple dilemmas have come to the fore, which compound these issues. All this makes for tougher forward conditions, if unaddressed, and might yet delay upstream recovery with rebalancing needed for countries and state players to return to the upward long-term inbound oil and gas investment trends found in the recent past.

Indeed, Africa’s contemporary state of play appears less propitious than even one year ago, following this coalescence of macro and country shifts that have combined in detriment with the latest crude market downslide. Libya has imploded; the Sahel is riskier; Central African Republic is off-limits to most; South Sudan is a de facto write-off but for the bravest; Nigeria remains without stable contract conditions, as the PIB is stuck in the political mud; South Africa is yet to resolve its legal framework for the offshore and in mandated state equity provisions – to cite but a few.

Many governments face oil-induced cash crises; penal-styled terms or residual resource nationalism ‘stickiness’ continues to deter cautious investors; more countries have retained and some enhanced capital gains taxes on primary market acreage transactions (DRC, the latest); uncompetitive ‘state take’ levels remain high and belie the likelihood of maximising near-term foreign company inflows; onerous local content obligations, often malformed, add costs and deter corporate entries and in-place players; and so on. Africa’s state oil companies – with few exceptions – are mostly trapped in this web of complex and unwelcomed market conditions, even while new state oil and gas entities are being formed and brought into play (Uganda’s the latest).

Unresolved problems abound. South Africa’s PetroSA has incurred huge financial losses and awaits new leadership, while the Nigerian NNPC is yet to be reformed, and may be split up. Ghana’s state gas entity was formed, then soon disposed of after heavy losses. Many state firms retain non-commercial aims, baggage from a past long-gone; few have been suitably restructured for stand-alone survival, let alone global competitivity. Many of them still have weak balance sheets, some no control over budgets or investments, and most play an unhealthy role in managing extraneous non-commercial objectives with too few independent licensing agencies found, while several newly formed state oil entities are yet to fully launch off the runway.

Platforms and Networks

In the boom times, it might have been easier for the continent, countries and state oil players, with their ministerial oil officials, as well as the corporate world, to float along on the rising tide: no longer. Even then, the longer-term players and enlightened used platforms and networks like those of Global Pacific to engage with wider industry audiences. It enabled them to solicit new investment partners, plus benefit from the targeted interfaces provided, and shape competitive strategies along the lines of research and seasoned advice that had long been provided.

The African Institute of Petroleum, established 1996, is one of these enduring entities: it has long provided mechanisms for connecting key players one to another, counselled and advocated for countries to retain suitable terms and conditions that are always best to be struck in the top-quartile, and competitive within Africa and with the rest-of-world. The PetroAfricanus Club (established 2004) has brought over 6,000 state and private oil companies together to facilitate deal-flow, and showcase both to the benefit of all. More efforts will follow here, to stimulate corporate entries into Africa and encourage investment maximisation and best-practice. The International Licensing Association, formed in 2006, not just for Africa, has encouraged open and independent, world-class acreage and asset licensing, with knowledge to facilitate world-scale roadshows and marketing. This mode is essential in a market replete with multiple competitors – well over 150 countries are seeking scarce exploration dollars.

For targeted and specific talent-niches, the Global Women & Petroleum Club, established in 2001 and led by Global Pacific & Partners Chief Executive Babette van Gessel, has pioneered research, skills formation and special events to enable state and corporate players to recognise and enhance the role of women inside Africa and in the global oil industry.

Global Pacific & Partners is enhancing these platforms and networks to serve the industry in Africa better in future, while adding to this with its landmark Africa Oil Week, now in joint-venture, and by continuing efforts on research and strategy briefings dedicated to Africa (on corporate players and state oil firms), including in-depth knowledge-banks on Africa’s upstream, all accessible online. It also provides critical information to thousands of individuals daily across Africa and amidst the fourth estate, often much-neglected, by building communications for the industry in Africa via related oil and gas endeavours.

Shaping Africa’s Future

Africa’s state controlled national oil companies face multiple dilemmas.The much-changed ‘big picture’ paradigm should guide current and future strategies for governments, national oil companies and private players – the last are already mostly very responsive, through sheer brutal necessity.

Africa’s state controlled national oil companies face multiple dilemmas.The much-changed ‘big picture’ paradigm should guide current and future strategies for governments, national oil companies and private players – the last are already mostly very responsive, through sheer brutal necessity.

Costly state financing of subsidies to non-oil energy sources, companies and investments – renewables, and the like – should be cut or preferably eliminated, and level-playing fields in energy made the operating norm. Subsidised fuel too is an expensive game, to be best reduced and excised in time. Open investor landscapes for corporate oil and gas entry and flexible operation need maximal encouragement. Preferences for state oil players can often only be sustained at cost to slower rates of economic growth and the reduced level and rate of unlocking-in natural capital for productive investment.

The politically seductive tilting of the playing fields for ‘locals’ usually only comes at hidden net costs to long-term capex inflows and maximal hydrocarbon development. The ideology of state-driven mandated local content – beloved by many – falls into this category, with short-term benefits typically gained only at higher long-run operating cost.

African national oil companies – a large and growing complex, managed and operated at less than world-class level – could be greatly reformed or restructured, and some partially privatised, to secure public and social benefit, with added net economic welfare. The lessons of the past and present tell of the necessity to reduce over-dimensioned state-protected behemoths; to shed non-commercial aims, preferably to ministries; and to reshape state oil firms’ portfolios to offload unviable or non-performing assets. It would be better to privatise what cannot work or pay its way, or lacks the rubric of a ‘public good’, often found in ventures that are non-core, or accumulated from inherited history, including peripheral subsidiaries. Governments would be best served by divesting acreage licensing to professional autonomous entities.

None of this is rocket science: but too little of these reforms have been executed. Without deep reform many countries and their state oil entities might yet be drowned in the on-going tidal onslaught. There are numerous industry platforms dedicated to Africa and several beneficial networks that could be more rigorously employed by governments and state oil players to move ahead of this current cycle of crisis.

Sound advice, reforms and commercial platforms and networks could move Africa forward and upstream, to avoid sliding down the crude backtracks leading to the unenviable position of second-best or also-rans in this de facto hyper-competitive world.