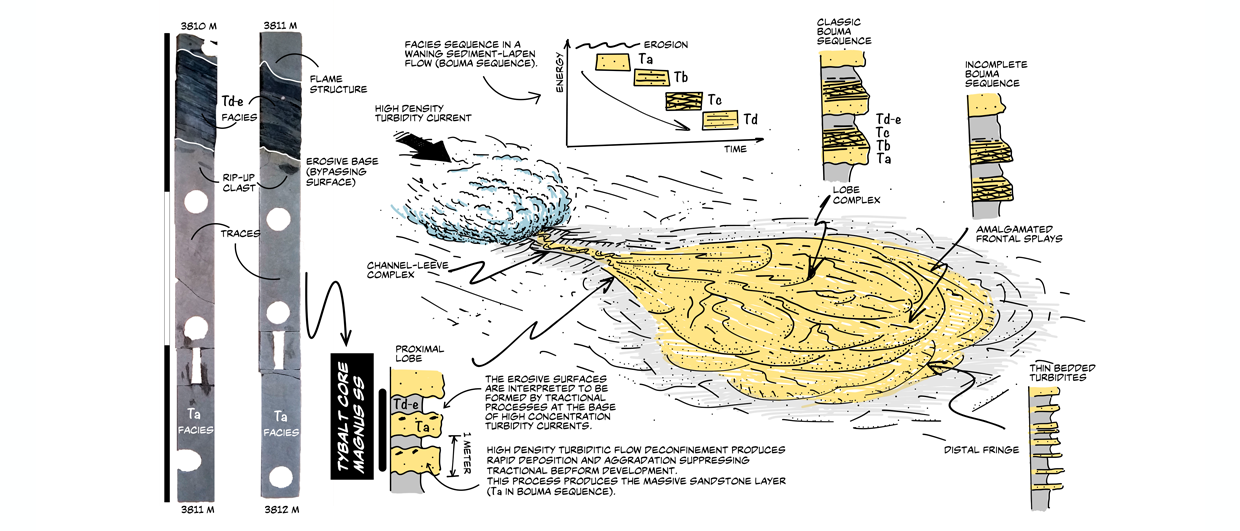

The Bouma sequence, proposed by Arnold Bouma, has been a cornerstone in the interpretation of turbidites and high-density sediment currents since its publication in 1962. The Bouma sequence is a model of sediment-laden gravity flows and sedimentary structures. It represents the waning of a turbidity current as it passes over a single point.

An ideal Bouma sequence begins with a massive sand interval (Ta) characterized by high-energy. This interval often has mudclasts ripped from the base and dish structures may be present. This facies is followed by a laminated sand interval (Tb). Although the flow continues under upper flow regime conditions where energy is high enough to carry sand grains by traction, this facies represents a decrease in the energy of the sedimentary flow. We then move on to sands with ripple lamination (interval Tc), followed by laminated silts (interval Td), and finally, fine laminated silts (interval Te), marking the end of the turbiditic sedimentation process.

A rare find

However, it has been known for a long time that the entire Bouma sequence is quite rare to find, either because of erosion of the top part of the succession, or the high-energy initiation is missing in the more distal parts of the turbidite lobes. Where to place the Tybalt cores (well 211/08c-5) in that regard?

When looking at the light-coloured sandstones in the photo, the most striking observation is that they are structureless from the base to the top of the succession, clearly suggesting that these sands belong to the massive sand (Ta) type of deposit. In other words, the elements expected as a result of decreasing energy conditions are missing. For that reason, the sediments in this core are likely from a more proximal part of the lobe system.

Another interesting observation is that it is not only the base of the sandstone that shows an erosional contact; the top is also characterized by an erosional transition to the overlying mudstones. This can be explained by another turbidite flow that did not result in deposition at this particular location but resulted in the removal of part of the previously deposited succession instead.

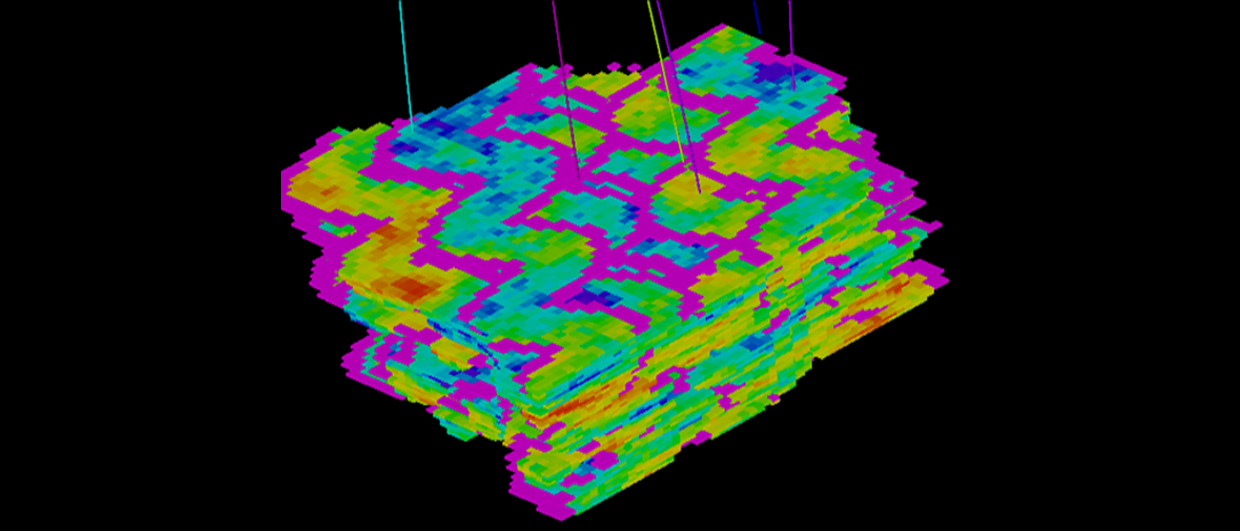

So, even though the cores here do not show the full Bouma sequence, the concept can still be applied. A generalized recognition of all the Bouma sequence facies and their evolution throughout the turbidite lobe is presented in the illustration.

This article can also be found in Issue 1 of the GEO EXPRO magazine, which can be downloaded here.