In August this year, Reuters reported that Denmark and Costa Rica are trying to forge an alliance of countries willing to fix a date to phase out oil and gas production and to stop giving permits for new exploration, government ministers said and documents showed.

It is an example of the way countries deal with the challenges climate change present.

On one hand, there are initiatives attempting to leave the impression that phasing out oil and gas is happening. On the other hand, if one looks a bit further, there is the realisation that our reliance on fossil fuel is still very much live.

The latter very much applies to Denmark.

Yes, a proposal for a change to the Danish Subsoil Act has been put forth in the Danish Parliament on October 6th 2021. If the act is passed, exploration and production of oil and gas will no longer be legal in Denmark or on the Danish Continental Shelf Area from December 31 2050.

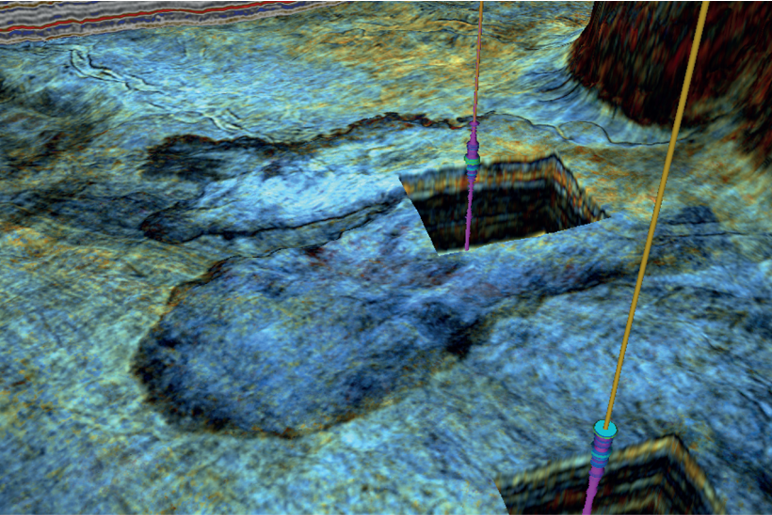

However, the same proposal also stipulates that companies – both established players in the Danish sector as well as new ones – can still apply for an exploration licence in the Danish North Sea sector west of 6°15’ E where any remaining prospectivity still resides.

In addition, as we already reported in August, the proposed year of 2050 will ensure that all remaining oil and gas reserves in the Danish sector will be able to be produced, even when some new discoveries are being included.

It is a clear demonstration of the very complicated situation countries find themselves in with regards to wanting to be seen as taking decisive action against climate change but also being aware of the dependency on fossil fuels. Denmark features in the news as a country setting an end date to oil and gas production and exploration, but quietly allow everything to be produced including the possibility of future finds.

On top of this, as the Financial Post illustrated in a story this month, the continued reliance on oil also leads to importing more from regimes hostile to European values, including Europe’s post war practice of open societies, liberal democratic norms and tolerance. About two-thirds of oil imported into Europe between 2005 and 2019 came from countries with poor records for human freedom. This should be something that also features on the agenda when discussing future projects.

In summary, it is time to become realistic and accept that the natural decline of production from European oil and gas fields is already surpassing demand. Any further constraints on finding additional near-field volumes – as is the trend in Europe already – should be carefully balanced against the drawbacks of importing hydrocarbons from anywhere else.

HENK KOMBRINK