When I visited the MEOS GEO Conference in Bahrain last in 2025 and spoke to some people about projects currently ongoing in the region, it slowly dawned on me that there was one project that had escaped my attention. One that is of such a scale that it is actually a miracle that it had never appeared on my radar before: The Jafurah unconventional gas project in Saudi Arabia. Even when I attended the IPTC Conference in Dammam in February 2024, browsing through my notes, I could not find a reference to this project that was happening not too far to the southeast of the city.

Two analysts from S&P Global woke me up; they raised the Jafurah project on several occasions whilst we were driving back to the hotel after a long day at the show. As happens often, it is those conversations with industry insiders that form the inspiration to write a story.

Two analysts from S&P Global woke me up; they raised the Jafurah project on several occasions whilst we were driving back to the hotel after a long day at the show. As happens often, it is those conversations with industry insiders that form the inspiration to write a story.

The scale of Jafurah is huge. The unconventional gas project entails drilling around 10,000 wells. And that is not the only thing that makes Jafurah special; it is even more special when one realises that these wells are sitting idle until they are being opened all at once, when the project will finally deliver first gas. That is a very different strategy compared to how unconventionals work in the USA. There, wells are drilled, fracced and put on production straight away. The learnings of one well form the basis for drilling the next. It is the way to drain the sweet spots most efficiently.

However, with the Jafurah wells, this learning curve does not exist. Sure, wells are probably being subjected to a short-term production test after completion of the frac job, but are then closed in until the entire project is ready. As someone who has followed the project from nearby said: “It is an experiment on a large scale.”

For this article, I draw on the input from several people I spoke to over a timespan of about a year. In a few cases, I was not even 100 % sure people were telling me something about Jafurah, but now, when pulling it all together, I became more convinced that they were. It shows the sensitivity around a project of this kind, which is understandable. To my knowledge, it is the first unconventional gas project on this scale that is being developed outside the USA and possibly Canada. And because it is being done in such a different way, i.e. through drilling the whole project first before putting it online in one go, it is worth being written about.

Hard beds and data scrutiny

The first time I seem to have heard about the project was through someone I spoke to at yet another conference earlier 2025. He was a driller and had spent six years in the desert working on Chinese rigs that were drilling “a huge gas field”, as he described it. Now, thinking back, it might have been Jafurah. He also said that the rigs were primitive; the beds were just a simple wooden plank with a thin sheet to sleep on. So, in order to lie comfortably, he had to scramble as much linen as possible to make a slightly softer bed.

He also told me that there were six rigs in a row, drilling in a grid-like pattern and completing four wells per pad. It sounds very much like the approach taken at Jafurah, based on conversations I later had in Bahrain. One of the last things he said was that the wells were all drilled and completed before the surface infrastructure was put in place, adding that this was unheard of in the West.

This corresponds to what I heard through another conversation I had with someone who is probably directly involved with the wells that are being drilled. One of the things I remember him telling me is the scrutiny he and his team experienced when it came to using wireline logs to drill the wells. Let’s put it this way: The suite of logs to be used to find the landing zone was always under review. Of course, this happens all the time, but with so many wells to be drilled, all in the same formation, it is not a surprise that there is pressure on saving money in any possible way.

And saving money is probably required, because unconventional gas developments are a very different kettle of fish compared to conventional projects.

Conventional versus unconventional

As someone else with exposure to the unconventional business reiterated the other day, there is a big difference between unconventional and conventional projects. Margins tend to be much higher with conventional developments, simply because the geology is more favourable, with higher porosities and permeabilities. And there is a surprise in store sometimes, which means that production can also be much more favourable than anticipated. All thanks to the geology that ultimately remains hard to predict and model. Those sorts of presents are much harder to come by in the unconventional arena, because it is all about drilling wells. Many more than in the conventional domain. “And when it comes to engineering, there are no gifts,” I was told.

The unconventional industry is much more like a real estate game, I learned as well. In the USA, the money you can make in shale is not through production, but through the acreage you can sell. It starts with a small company proving the potential through drilling a few wells, and once this has been demonstrated, the value of the acreage goes up and can be sold. In the Eagle Ford, the value of an acre went up from $25 in 2000 to around $50,000 for the same plot of land a few years later.

At the same time, booking reserves in shale can be done at a relatively low cost, as it is seen as a continuous basin that can be tapped into at any location. You are not required to prove commerciality with so many appraisal wells as is the case in the conventional business. This is probably one of the drivers for some companies to enter the sector and bump their reserve replacement numbers. The reality is different, of course, with Shell entering the US shale patch more than 15 years ago as an example. Peter Voser, a Swiss accountant who became Shell’s CEO in 2009, decided to invest heavily in unconventionals in the USA, only to find out that production was not as rosy as they had expected. This subsequently led to the sale of their assets again, as well as the departure of Voser himself in 2013. Funnily enough, Shell is now back in shale.

Going back to Jafurah, we see another commercial dynamic. “Market conditions are very different in Saudi Arabia,” says Josef Shaoul, who has been working in the frac business for decades with Fenix Consulting Delft. “The Jafurah gas production is all meant to save burning oil for power generation, so in that sense the cost of the project is directly tied to the money that Saudi Arabia can make by selling the oil on the international market rather than the gas price itself,” Josef explains.

On top of that, Middle Eastern countries are adamant to develop their own gas resource rather than being dependent on supply from neighbours. “It would be a lot easier to build a pipeline to Qatar, but that is not an option,” adds Josef. “In that sense, the pricing mechanism is not at all driven by the economic factors that determine the same industry elsewhere.”

HOW NEW IS FRACCING TO THE MIDDLE EAST?

Hydraulic fraccing is not new to the Middle East. In fact, it has a long history. “Especially in Oman, a country that does not have all the same high permeability reservoirs as the other main producers in the region, fraccing has been applied to tight reservoirs for decades,” says Josef Shaoul. “This was further aided through the PDO partnership with Shell and the international links established that way,” he says. “In Algeria and Libya, fraccing has also been taking place since the 1970s.”

“However, it is important to keep in mind that until recently, fraccing in the Middle East has focused on tight reservoirs and not on the shales that are being targeted in the US,” says Josef. “For instance, in Oman, there are now projects ongoing that include fraccing of existing oil wells in an attempt to arrest the decline from mature fields. Some people in the Middle East might call it unconventional when a frac job is required, but it is important to realise that the reservoir quality in those cases is still a lot better than what the unconventional reservoirs in the US look like.”

But regardless of the type of formation that is subjected to fraccing, the characteristic of a successful frac is that production is high initially, with a steep decline. “Some people don’t get that and think that production should be sustained,” explains Josef. “But that’s not how a successful frac looks like. The frac job would not have been needed in the first place if production had been sustained for a long time after it. This is what we need to explain often.”

“Fraccing is not the ultimate solution either,” Josef adds. “If there are no hydrocarbons in the reservoir, a frac job will not result in more production. That is another aspect that seems to be forgotten about sometimes.”

The wells

In Texas, there is an army of engineers in the field that continuously check upon things and tweak wells whenever this is required, further supported by people in the office who keep an eye on production data all the time. And it is based on that type of work that the next frac job is planned. This system of working with experience being built up as the basin is further unlocked is missing in Jafurah, where it is a single development concept that does not allow for learnings to be implemented along the way.

So, the big question that must be in many people’s minds is, how are the wells drilled on Jafurah going to produce, after having been shut in for about ten years in some cases?

Someone I spoke to, who has significant expertise in the engineering side of the unconventional business, is not so sure about the success of the operation. He fears that scaling and liquid loading will be issues that might require a re-frac for some of the older wells. Josef Shaoul is more optimistic about it. “When a short clean-up and production test is carried out immediately after the well has been fracced, there is a good chance the well will start producing as expected even after it has been sitting closed in for a while,” he says. “I have seen this in Oman, where an LNG terminal was completed whilst the wells for the project had already been drilled. They were not closed in for ten years such as some wells at Jafurah, but still up to about a year. These wells seemed to start production just fine once the valves were opened.”

The geology of Jafurah

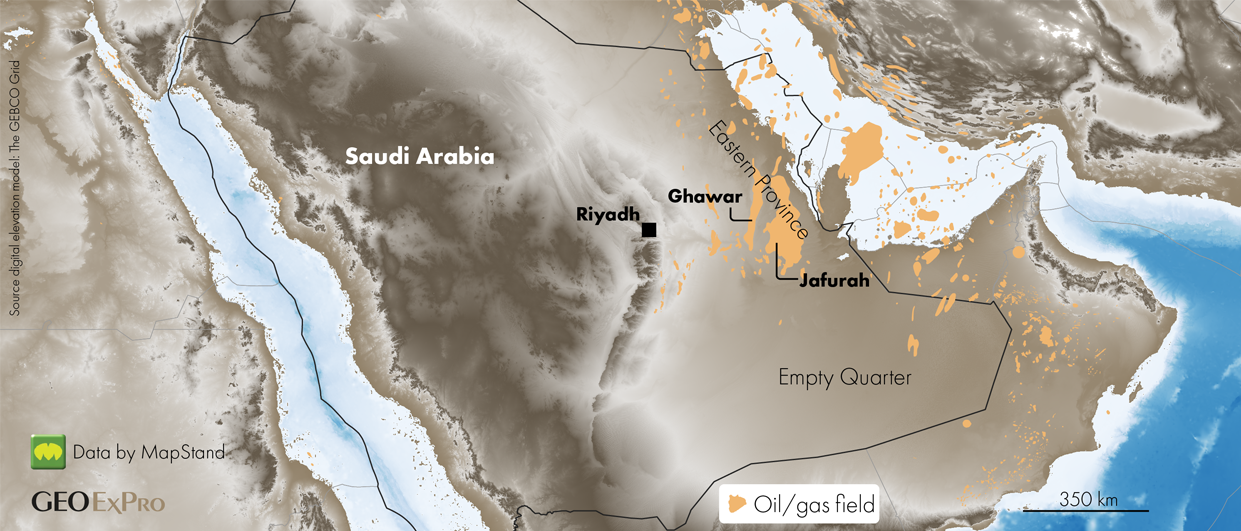

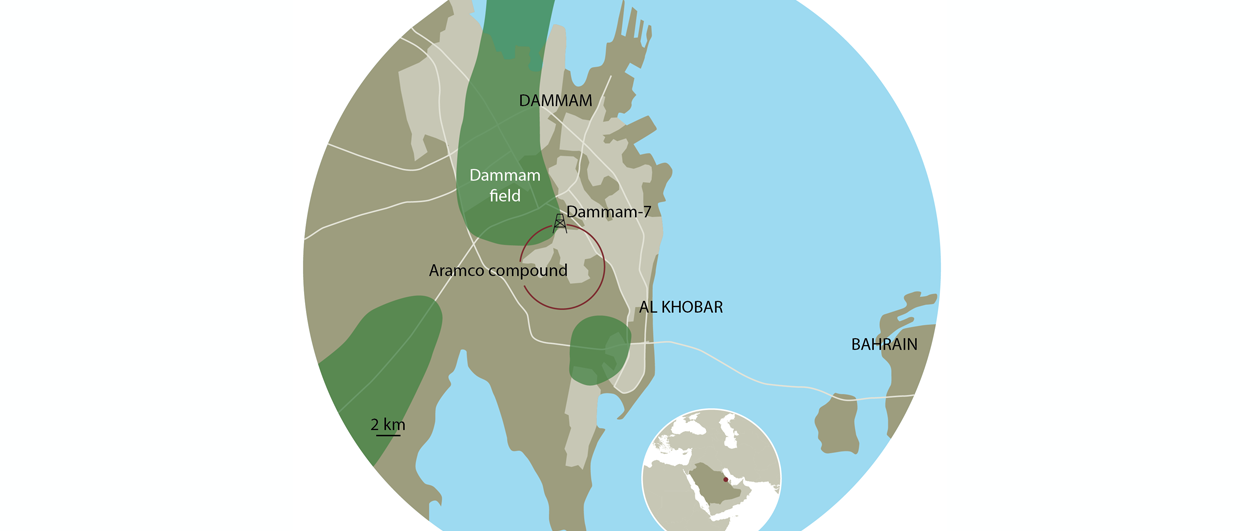

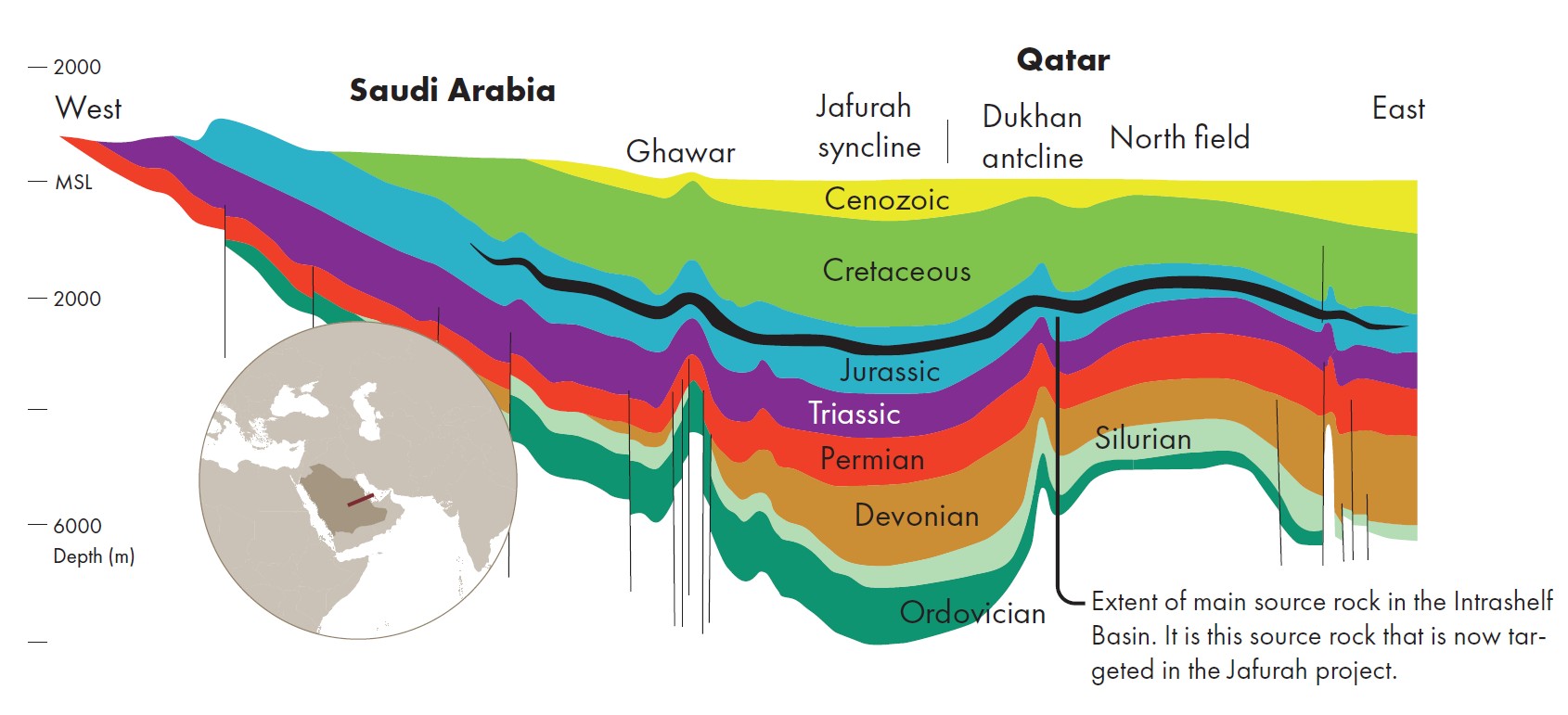

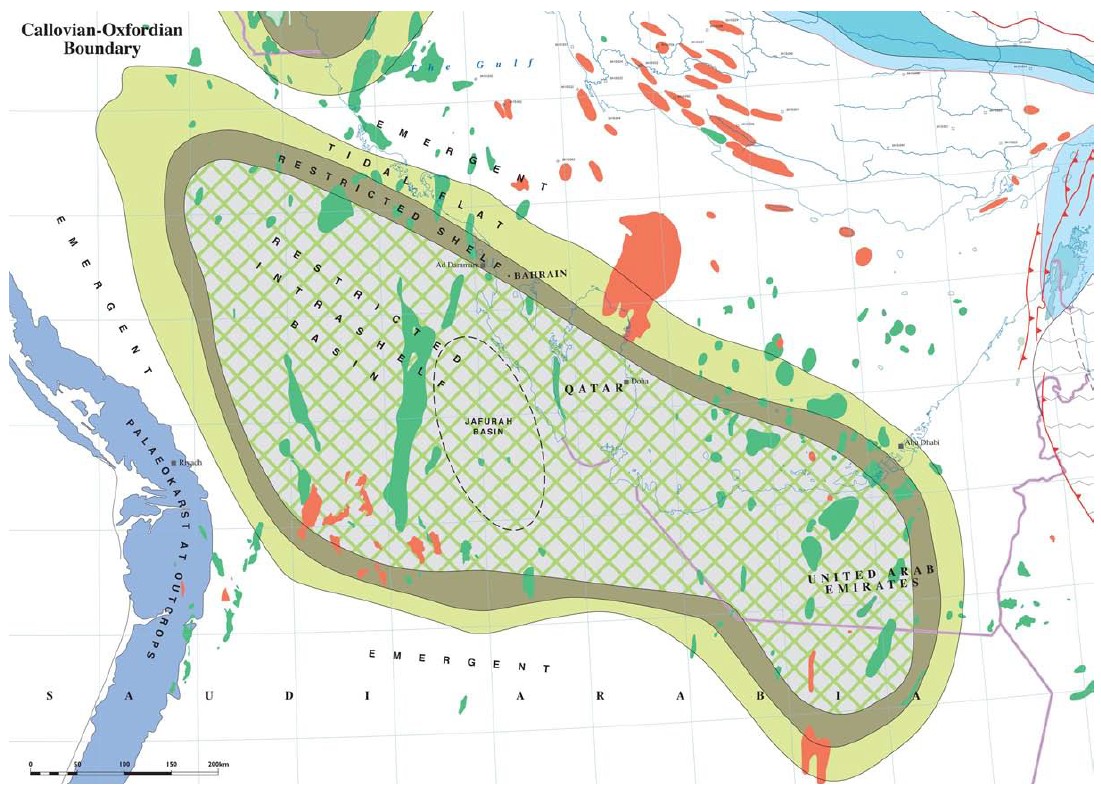

The Jafurah ‘basin’ play is within the broad synclinal trough between the Ghawar anticlinal trend and the Dhukan anticlinal trend, structures formed during the Tertiary when the Arabian Plate collided with the Eurasian Plate. The Jurassic interval of interest formed at the Middle and Late Jurassic boundary within the Arabian Intrashelf Basin. To find out more about the geology of the Jafurah basin, I travelled to London King’s Cross to meet with Augustus (Gus) Wilson in a café not far from the station.

Gus worked for Saudi Aramco a long time ago, from 1973 to 1981, and later worked on other projects in the area, keeping alive his fascination for the geology of the Arabian Platform. Five years ago, he published a book on the regional geology of the area, Geological Society Memoir 53, which can be seen as a culmination of his studies in the region.

Gus remembers the years he worked at Aramco vividly. “One of the projects I worked on was to identify and map all the source rocks in the region,” he says. “At the time, the understanding of what was actually the source rock of the Ghawar and other oil fields was still in its early stage,” he says. “Some people claimed that the source rock was the same reservoir carbonate in which oil was found, but our analyses proved that the reservoir carbonates were unlikely to be the source rocks because they had very low TOC’s. Instead, our analyses of the slightly older laminated black organic-rich carbonates clearly suggested that these were the prime suspects.”

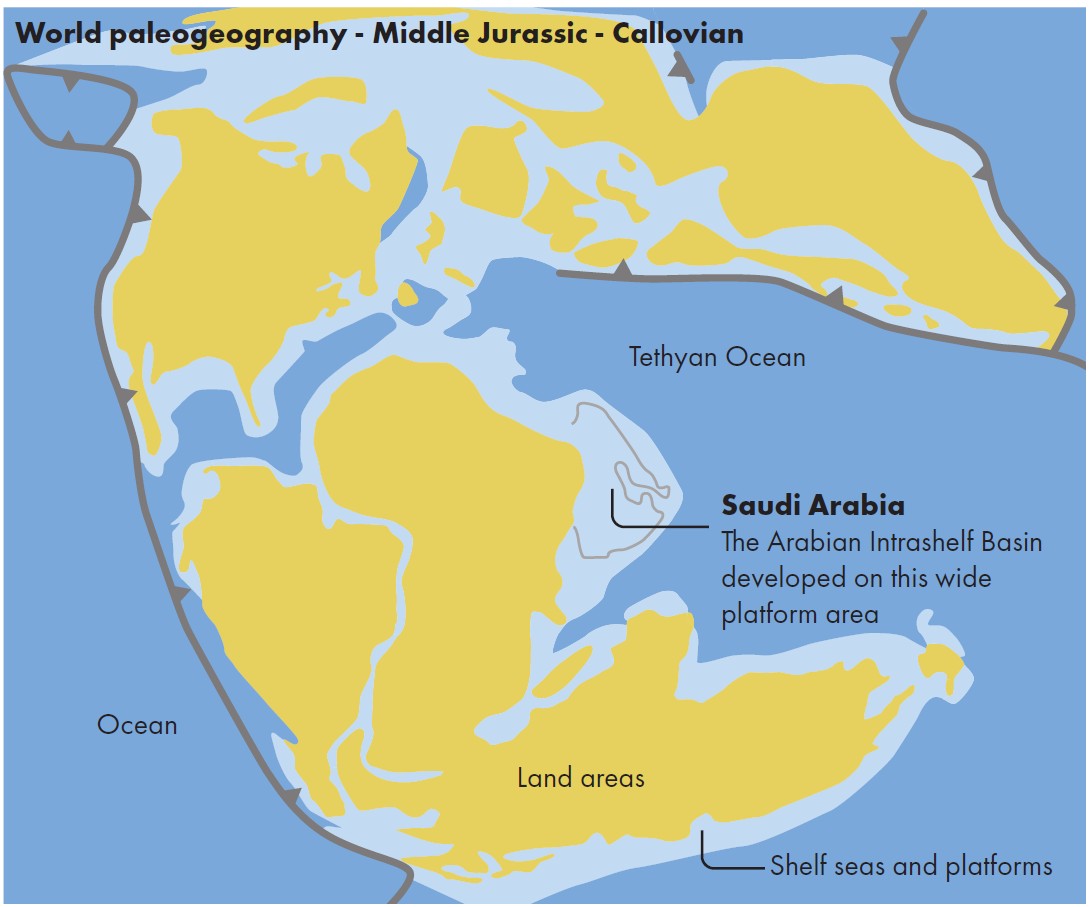

These early Late Jurassic (Oxfordian) source rocks of the Lower Hanifa Formation were deposited in what is described as the Arabian Intrashelf Basin. This basin formed on the eastern margin of the Arabian Platform, facing the Tethyan Ocean.

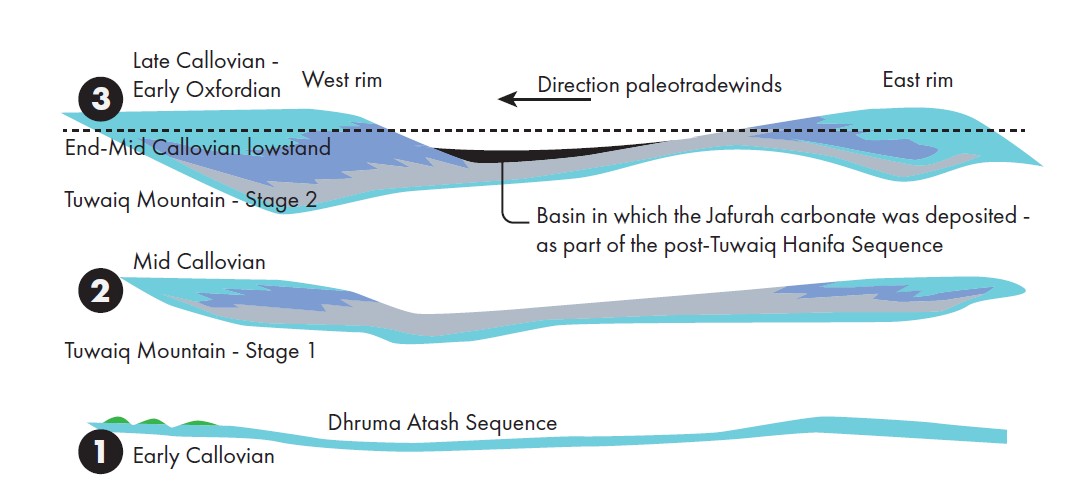

The Arabian Intrashelf Basin facies are underlain by regionally extensive and exceptionally uniform platform carbonates belonging to the Dhruma Atash Sequence, deposited across the Arabian Platform during Late Bathonian to Early Callovian times. As Gus describes in his book, it is hard to interpret the origin of such a flat, regionally extensive interval of similar facies.

The transition to the subsequent Tuwaiq Mountain sequence, which is described as the time when the depositional geometry of the Arabian Intrashelf Basin really took shape, starts with the development of a huge body of water across a wide area, surrounded by a rim of shallow water carbonates. The shallow water carbonates forming the rim prograded basinwards over time, but projecting the position of the Jafurah development onto this map, the Jafurah region maintained a more distal position in the basin, away from the shallow carbonate rims.

The Tuwaiq Mountain sequence of shelf progradation was probably terminated due to a global lowstand at the end of the Callovian. It is during that lowstand system in which the source rock that is now targeted by the Jafurah wells was deposited.

The base of the high-TOC interval is a very sharp boundary, indicating a sudden change in depositional environment. This has been observed by Gus in many wells across the region. But what are the further characteristics of the succession?

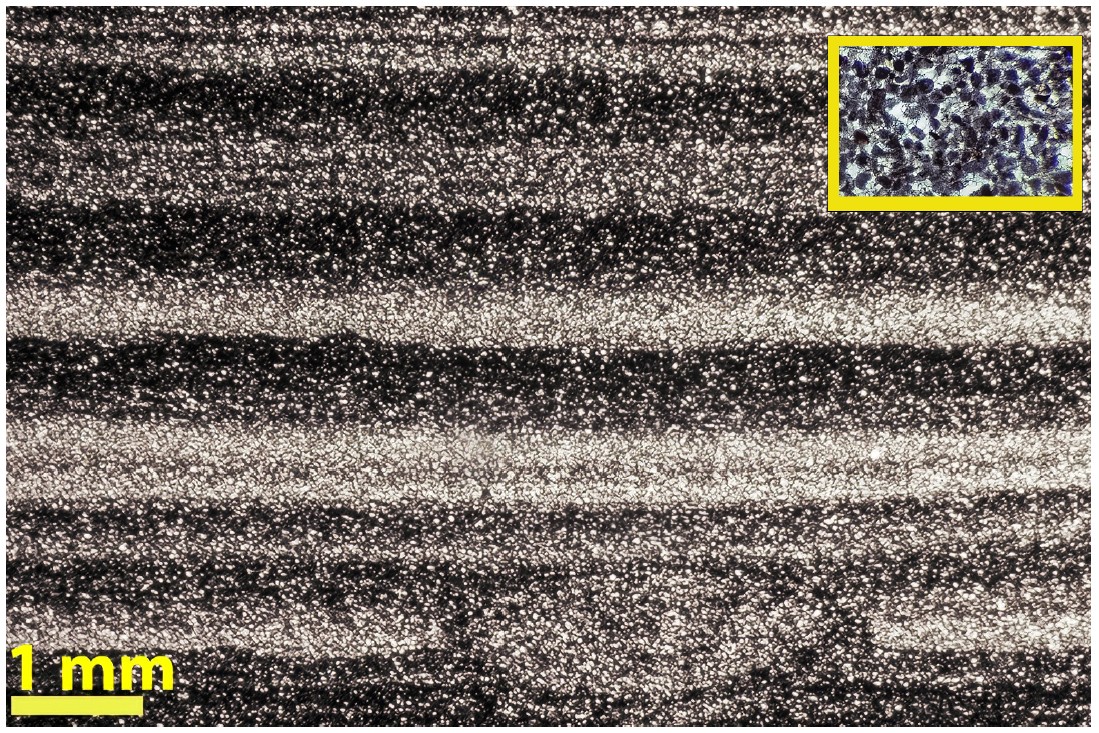

In contrast to what some people think, the source rock is not a shale, but a carbonate. To be more precise, it is a very organic-rich laminite, characterised by the alternation of light-coloured laminae of micropeloidal micrograinstone and dark organic-rich carbonate laminae. The light-coloured laminae show what can be interpreted as small-scale scouring, which may indicate reworking of the peloids by bottom currents. Gus adds that he has never seen a similar facies during his 50-year career working with carbonates of very different ages, although he does write that others have found such facies elsewhere.

Then there is the thickness of the source rock, which increases going from the east of the Intrashelf Basin to the west. Gus attributes this to the prevailing wind direction at the time of deposition, mostly blowing from the east. This meant that the western rim of the basin had a much higher wave energy than the eastern margin, which led to higher rates of deposition in the west, and hence a thicker source rock. There was also more accommodation space developed in the west.

The total thickness of the source rock is not very easy to reconstruct because of a lack of published well data, but the estimations vary from 10 m to a bit more than 40 m in the Jafurah area. A source rock maturity map compiled from published data in the book Gus published shows that the area of the Jafurah project is currently in the gas-generating window.

NEW TECHNOLOGY

Josef is of the opinion that laser technology, which some sources say has been used to help stimulate the Jafurah wells, is not commonplace yet. He has not come across it as a way to replace currently applied fraccing technologies. “Aramco has a tendency to support R&D and test new technologies,” he says, “but it is probably far off from being implemented widely. Even when people have wanted to work with lasers for a long time, I have yet to see it appear on the market as being truly disruptive. In unconventional applications, the key parameter for production is frac area. No other technology can compete with hydraulic fraccing in creating a fracture area for inflow of gas or oil.”

Final thoughts

Even though lots of aspects of the Jafurah development remain unknown because of data confidentiality, it is clear that the development is of a massive scale and because the estimated number of 10,000 wells will be hooked up after having been closed-in for up to ten years in some cases, it is very much the question of how these will behave during the first phase of production. However, as we have seen from the geological observations, the Lower Hanifa source rock in which the wells are being completed probably has a very strong lateral continuity, which is probably an advantage for Aramco, as they lack the opportunity to find the sweetspots in a similar way as their American colleagues do in the Permian Basin. Whether it will be enough to guarantee a big success remains to be seen, but it is obvious that Jafurah is very much an unconventional unconventional project.