Friends and colleagues have no trouble finding feisty adjectives to describe the late Ruth A.M. Schmidt, one of the United States’ early female geologists. After all, it was Schmidt’s frank and no-nonsense attitude that allowed her to step assuredly into a heavily male-dominated field in the 1930s and chart a historical career, much of which remained unknown until her death on 29th March 2014 at 97 years old.

At a celebration of life service in her honour, many were surprised to learn how much the Brooklyn native cherished her privacy.

Schmidt was publicly noted for leading an inter-agency team of dozens of geologists and other earth scientists to remap the city of Anchorage at near record speed after the 1964 Great Alaska Earthquake, which she survived while working on a frozen Portage Lake. To date, it is the most powerful earthquake to strike North America, with a magnitude of 9.2.

In an article titled Geology in a Hurry, published in an October 1964 issue of the American Geological Institute’s Geotimes, Schmidt described the controversial effort to identify geologic hazards in Anchorage for the purpose of mitigating future risks to development and the production of preliminary maps in a mere three weeks.

“No one likes to be told his house and business are on landslide areas, but if they are, how much better is it to know it?” Schmidt wrote, her resolute intentions permeating every word. “Geologists have done their part as citizens to see that everyone has been made aware of the hazards of building on landslides and similar weakened and unstable areas. Let us hope they can continue to guide the city and to help see that disasters do not recur.”

Beneath the Surface

As revealed after her death, Schmidt’s career proved to be as riveting as the quake itself. As friends and family began packing up her modest Anchorage home, which doubled as a library and laboratory for countless slides of ostracods and foraminifera, information emerged chronicling a career fit for history books.

“I was overwhelmed by what I didn’t know about her,” said Sally Gibert, a land planner, geographer and longtime friend of Schmidt. Gibert served as Schmidt’s power of attorney when in 2005 signs of dementia began setting in. “She didn’t hide things, but she didn’t feel the need to talk about her accomplishments.”

Gibert was charged with the responsibility of distributing donations to more than 20 charities, mostly Alaska-based, and seeing that Schmidt’s coveted Alaskan art collection – including paintings by renowned geologist Marvin Mangus – was given to the Anchorage Museum of History and Art. She systematically emptied Schmidt’s home – a process that included using a professional archivist from the University of Alaska, Anchorage.

Documents unexpectedly surfaced that placed Schmidt in the heart of World War II in 1943. She was one of few female geologists employed by the United States Geological Survey (USGS) to participate in a top secret Military Geology Unit in Washington, D.C. Schmidt mapped areas suitable for digging foxholes and building observation posts and pillboxes for the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, in addition to finding the safest and most protected trails and terrain that could support bridges, and streams shallow enough to be forded.

The job spring-boarded Schmidt’s geological career during a time when many women were openly discouraged from the field, according to Anne Pasch, who taught geology at Anchorage Community College with Schmidt and was told by a dean at the University of Wisconsin in 1950s that he would not sign her diploma if she majored in geology. “Geology was one of the last scientific disciplines that was cracked by women,” Pasch said.

A micropalaeontologist by profession with master’s and doctorate degrees in geology from Columbia University, Schmidt approached her work with a calculating, detailed eye. Registered as an X-Ray technician during her studies, Schmidt applied her knowledge of radiology to palaeontology – her work no doubt catching the eye of the Military Geology Unit.

Room for a Woman

Taking advantage of the shortage of scientists during the war, Schmidt left behind teaching assistant jobs at Columbia University and New York University to participate in an unprecedented effort.

“Prior to the establishment of the Unit, geologists the world over were studying rocks, mountains, plains and streams, without realising their military significance,” stated a 7 October 1945 press release issued by the U.S. Department of the Interior. “It never occurred to them that their discoveries, important as some were to industry, might in any way be a primary factor in winning a war.”

One can only imagine the mental whiplash of moving to Washington to join a team of draftsmen who were ordered to “Don’t Think – Act.”

“The Military Geology Unit went into high gear and stayed there,” the press release stated. “They became the hardest and fastest working scientific group in history.” For the first time, geologists became an integral part of the war effort, heavily relied upon to churn out maps as if part of an assembly line. “Geologic and topographical maps gave up the innermost secrets of enemy terrain,” stated the press release. The maps “resulted in the saving of thousands of American and Allied troops.”

Schmidt’s employment with the USGS in Washington continued after the war. She worked for the Palaeontology and Stratigraphy Branch, the Organized Lexicon Project, the Palaeotectonic Map Project, and the Mineral Classification Branch.

Her professional strides made an impression on Hank Schmoll, a former co-worker of Schmidt who recently unearthed a USGS pamphlet circa 1947 that included a section titled ‘Women in Geology’. It outlined their limited need in the field except during times of war and in laboratories. “All the good stuff was for men only,” Schmoll said.

Included in the brochure was a staged photo of five women (see photo, above), one looking down a stereoscope, and others with maps in front of them. To the best of Schmoll’s knowledge, only one stayed the course: “That was a young Ruth Schmidt, who was looking over the scene with a slightly critical expression on her face.”

History: Part II

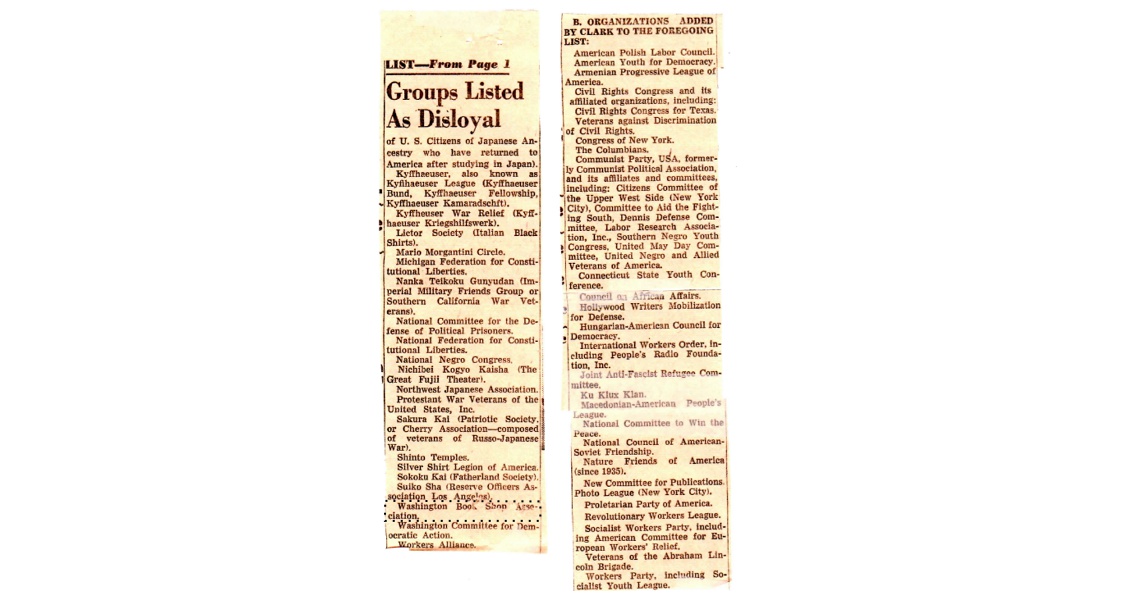

In the midst of her career in Washington, Schmidt unwittingly became part of history again – as the tables unexpectedly turned on her during the dark days of McCarthyism. Having joined the liberal, D.C.-based Washington Cooperative Bookshop, prompted by her interest in racial justice and a discount on books, Schmidt found herself the subject of investigation by the U.S. Department of the Interior’s House Committee on Un-American Activities, as the bookshop was deemed a ‘communist front’ by the U.S. government, and its board members ‘subversive’.

Not a communist and refusing to relinquish her innocuous, lifelong membership for which she paid $5, Schmidt remained a member and even served briefly on the bookshop’s executive board in 1947. She embraced the concepts of freedom and equality, which were promulgated by the bookshop through its advertisements, literature and guest speakers.

Two separate hearings, which took place in 1950 and 1954, forced Schmidt to hire attorneys, request 17 affidavits attesting to her loyalty toward her country from former professors, colleagues and friends, and subject herself to intense questioning to keep her job with the USGS. Each word of the hearing was recorded on carbon paper, which she kept filed in her home.

“She is extremely honest, frank and straightforward; a person of highest integrity in her dealings with other people, in her scientific thinking, and in her every-day living,” wrote a Houston-based friend in 1950 on Schmidt’s behalf. “At no time has she ever expressed sentiments of disloyalty to the United States Government.”

In the end, Schmidt was cleared.

Alaska Bound

In 1956, the USGS chose Schmidt to establish an Alaska district in Anchorage. She accepted the assignment with the same unshakable self-confidence she had during the hearings with the federal government.

At an Alaskan Science Conference in 1957, Schmoll was introduced to Schmidt for the first time. “I have never forgotten Ruth’s response: ‘Hello. Now here’s what I want you to do. These are the pages for the program book. They need to be stapled. Do it this way; don’t do it that way. And when you are done bring them to me, and I’ll tell you what to do next,’” Schmoll recalled. “Maybe that was a bit on the brusque side but…we’ve been friends ever since.”

USGS video describing The Great Alaska Earthquake, 1964

Once the Alaskan office was operational, Schmidt began what many say was her ultimate passion: teaching. As the first female geology professor and head of the Geology Department at Anchorage Community College in 1957, Schmidt’s warm side appeared more regularly. She taught from the heart, especially encouraging young women to study the sciences. In her later years, she would establish several endowed scholarships to support those wanting to study science.

“She had a very strong interest in teaching and helping students. It was the joy of her life,” Pasch recalled. “Geology has a problem because the general public doesn’t understand it. She was able to cross that line between professional lingo and the vernacular.”

In an August 1983 letter to the director of the science department, a female student wrote, “I can in all honesty say there is hardly a day that goes by that I do not look at the world differently and with more appreciation and understanding, armed with the knowledge acquired from Dr. Schmidt.”

When the community college, which initially shared a building with a local high school, moved into its own campus in 1970, Schmidt took charge of building a laboratory that would be used for more than 25 years. She worked as a consulting geologist and a professor, retiring from the university in 1984, but she continued professional consulting until about 2000, when she was 84. During this time, she helped Anchorage recover from the ’64 quake so it could rebuild its infrastructure with better knowledge about the lay of the land, and she served as an environmental officer on the Trans-Alaska oil pipeline in 1974. Her years of analysis of foraminifera helped scientists to conclude that the Bootlegger Cove Clay, which underlies parts of coastal Anchorage and tends to liquefy during earthquakes – is thousands of years younger than once thought.

A Softer Side

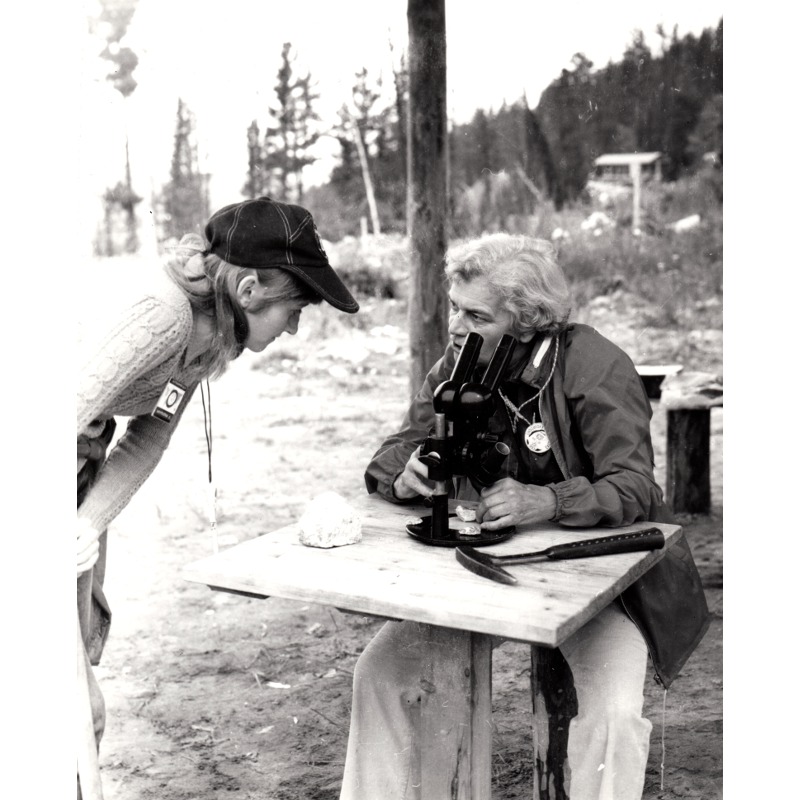

One of Ruth Schmidt’s greatest delights was mentoring young geologists. (Source: Courtesy of Sally Gibert)Even as dementia took an increasingly strong hold over her mind, the importance of education never left her thoughts. Forgetting that she had helped fund college for Gibert’s two daughters, she often asked about their plans to attend a university and about their career goals.

One of Ruth Schmidt’s greatest delights was mentoring young geologists. (Source: Courtesy of Sally Gibert)Even as dementia took an increasingly strong hold over her mind, the importance of education never left her thoughts. Forgetting that she had helped fund college for Gibert’s two daughters, she often asked about their plans to attend a university and about their career goals.

“In hindsight, I realise she mentored me as well,” Gibert said. “Her direct, cut-to-the-chase style was amazingly effective, and so outside the norm for women – especially in decades past. She commanded respect and was always respectful to others. I started out with a ‘meek streak’ and she showed me you don’t have to play ‘meek’ as a woman to be accepted. She gave me courage and confidence without my ever knowing it was happening.”

Schmidt may have had a thick outer shell, but – as any geologist might put it – it was highly porous. Many were drawn to her generous heart, her goodwill and her determination to do things right and well. Nearly 50 friends and former colleagues from Alaska and the ‘Lower 48’ attended her celebration of life last May. Representatives from nearly ten charities, serving a range of causes including science education, conservation, the arts and social justice, attended the service to thank her posthumously for her unexpected and generous bequests.

Feisty adjectives aside, Schmidt’s legacy was a love for geology, the Earth and enabling the study of both, most especially for other women who love a good challenge.