The 1st of August 2015 marks the bicentenary of the publication of a map which was to prove to be of extraordinary significance to the science of geology. The map entitled: “A delineation of the Strata of England and Wales, with part of Scotland” was made by William “Strata” Smith. Not only did Smith publish the first ever nation-wide geological map but he also laid the basis of what is now known as stratigraphy. As part of the bicentennial celebrations, a new website William Smith’s Maps – Interactive website has been established.

Humble Beginnings

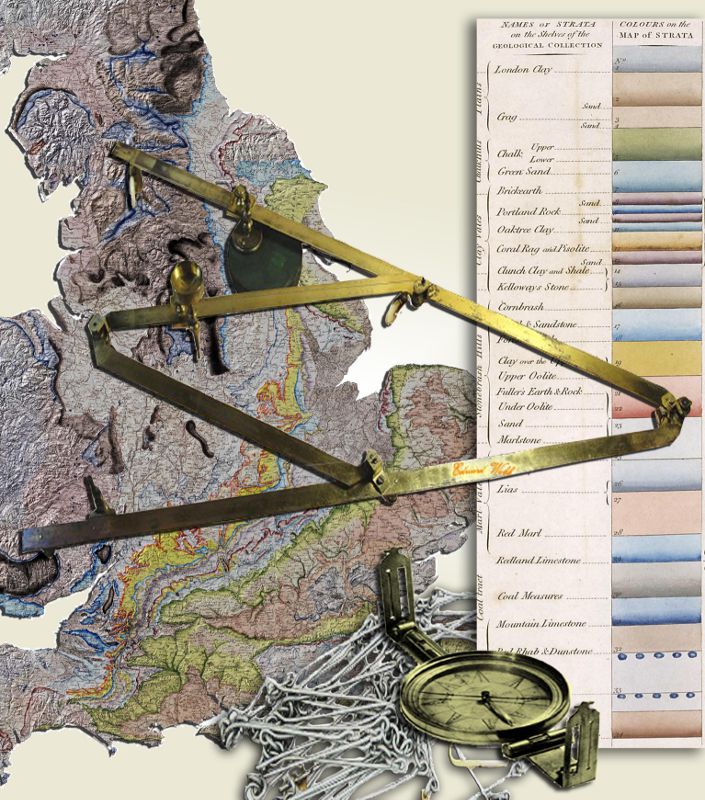

Mapping tools similar to those that would have been used by William Smith. (See text for more details)William Smith was born on 23rd March, 1769 at The Forge, Churchill, Oxfordshire, the son of John Smith, the village blacksmith and his wife, Ann. From humble beginnings he went on to train as a land surveyor. Shown in the illustration are some of the instruments which would have been familiar to Smith, they include measuring chains, surveying compass and a pantograph (used for tracing or copying).

Mapping tools similar to those that would have been used by William Smith. (See text for more details)William Smith was born on 23rd March, 1769 at The Forge, Churchill, Oxfordshire, the son of John Smith, the village blacksmith and his wife, Ann. From humble beginnings he went on to train as a land surveyor. Shown in the illustration are some of the instruments which would have been familiar to Smith, they include measuring chains, surveying compass and a pantograph (used for tracing or copying).

Early in his career, Smith was employed as a land surveyor on an estate in the Somerset coal field and it was here that he encountered the work of another geological pioneer, John Strachey, who more than seventy years previously had made the first real geological cross-section of the coal field. Smith’s work impressed local landowners and as a result he was asked to survey routes for the Somerset coal canal which was intended to take land-locked coal to the sea and, via other canals, ultimately to London.

The Somerset Coal Canal played an important role during Smith’s formative years. Smith surveyed routes for the canal in 1794 and would have been involved with excavations which started in 1795. In an era before motorway and railway cuttings, canal excavations were an ideal way to see vertical sections through strata. In Smith’s case he also had the advantage of seeing comparable sections in the two branches of the canal and also he knew, by measurement, the precise level of the canal cuttings. By the end of 1795 he had deciphered the local order of strata from the Great Oolite down to the Triassic “Red Ground” and soon after noted his critical observation that some of the strata contained fossils and those that did could be identified by them. Today it is easy to underestimate what an achievement this was; Smith had managed to separate several repetitious clay formations and also to separate the Upper and Lower Oolite. By August 1797, Smith had made his first attempt at a more general order of strata starting with Number 1 “Chalk Strata” and descending to Number 28 “Limestone” below the Coal Measures. During the course of several iterations this “Order of Strata” evolved into the geological table, part of which is shown in the illustration. Many of his stratigraphic names remain in use today.

After losing his position as a surveyor for the Somerset canal in 1799, Smith travelled the country seeking work as a land drainer, sea-defence builder and mineral prospector. It was during this time that he visited the site of an intended colliery at Cooks Farm near Bruton in Somerset and using his knowledge of stratigraphy advised that the boring was far too high in the geological succession to ever find coal. The advice was ignored and many of the shareholders in the mine went bankrupt.

First Maps

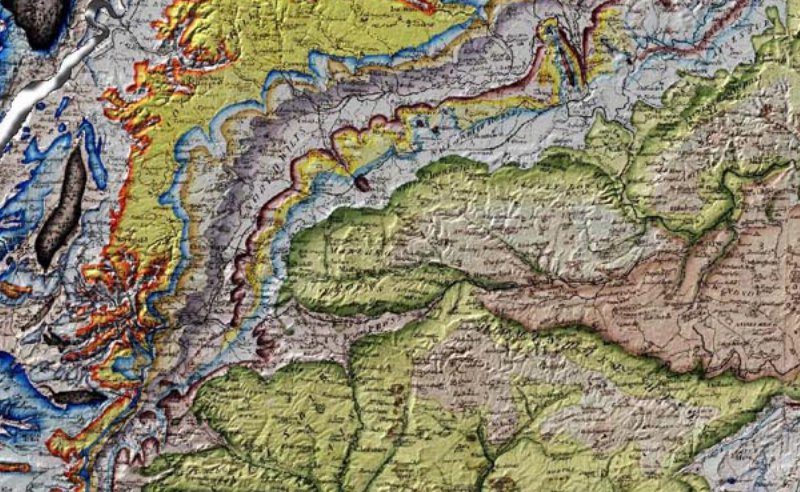

Detail from a hand coloured William Smith map, showing his innovative use of graduated shading.Smith’s first attempt at a geological map was an odd circular map around the city of Bath; later he made a geological map using John Cary’s General Index Map of England and Wales. Smith had some financial support from Sir Joseph Banks and others but largely financed his map-making from his own resources. John Cary was ultimately persuaded to prepare an elegant new base-map of England and Wales at a scale of approximately 5 miles to the inch. Smith then reduced his observations from more detailed maps, probably using a pantograph, on to the new map. The map was published by Cary in 1815. Each map was hand-coloured and because of Smith’s innovative use of graduated colour, individual strata appear to levitate from the two-dimensional plane of the map. A part of his map is shown in the illustration and here the three-dimensional aspect has been further reinforced by use of a modern hill shade.

Detail from a hand coloured William Smith map, showing his innovative use of graduated shading.Smith’s first attempt at a geological map was an odd circular map around the city of Bath; later he made a geological map using John Cary’s General Index Map of England and Wales. Smith had some financial support from Sir Joseph Banks and others but largely financed his map-making from his own resources. John Cary was ultimately persuaded to prepare an elegant new base-map of England and Wales at a scale of approximately 5 miles to the inch. Smith then reduced his observations from more detailed maps, probably using a pantograph, on to the new map. The map was published by Cary in 1815. Each map was hand-coloured and because of Smith’s innovative use of graduated colour, individual strata appear to levitate from the two-dimensional plane of the map. A part of his map is shown in the illustration and here the three-dimensional aspect has been further reinforced by use of a modern hill shade.

In the early 19th century Smith was a jobbing geologist in a highly stratified and class-ridden English society. The Geological Society of London was founded in 1807, initially as a dining club for gentlemen interested in geology; the first president was one George Bellas Greenough who was to prove to be Smith’s nemesis. Smith’s humble position as a tradesman precluded his admission to the Society. Greenough, through his inability to understand stratigraphy, completely disregarded the value of Smith’s work yet he liberally plagiarized his map. Sales of Greenough’s later 1819 geological map of England and Wales inadvertently added to Smith’s financial woes which ultimately led to his imprisonment for debt. Incidentally, Greenough was no aristocrat; he was nouveau riche, his fortune based on his grandfather’s business which purveyed tinctures and lozenges for toothache and other ailments. It was not until 1831 that Smith was to be honoured by a new generation of Fellows of the Society as the first recipient of its Wollaston Medal.

William Smith had undoubted genius, yet he was not a theoretician. He was a practical man with little interest in the grand idea or the unifying theory. He was however, a keen observer with an eye for landscape and an extraordinary ability to think three-dimensionally. His map is a masterpiece and his understanding of the order of strata remains an enduring geological legacy.

Interactive Website

William Smith, the blacksmith’s son who became the ‘Father of English Stratigraphy’. Artist: Hugues Fourau (1803-1873).The William Smith’s Maps – Interactive website has been generously funded by a grant from the UK Onshore Geophysical Library (UKOGL). It is a free-to-all educational resource designed for teachers and students as well as academicians and anyone with an interest in the life and work of William Smith.

William Smith, the blacksmith’s son who became the ‘Father of English Stratigraphy’. Artist: Hugues Fourau (1803-1873).The William Smith’s Maps – Interactive website has been generously funded by a grant from the UK Onshore Geophysical Library (UKOGL). It is a free-to-all educational resource designed for teachers and students as well as academicians and anyone with an interest in the life and work of William Smith.

A number of fine examples of Smith’s 1815 map are available on the website together with all of Smith’s published county geological maps and a number of unpublished county maps. The principal feature of the website is an interactive map viewer which enables users not only to view the maps but also to overlay one against another and compare them with modern geology, wells, seismic and current topographic maps. Users can also display Smith’s magnificent geological sections and view 3D animations of his maps. The website also has information on the map sources, Smith’s biography, stratigraphy, coordinates and maps in 3D.

There is also a section concerning the “Map That Might Have Been”. Using a mosaic of images from Smith’s county maps (published and manuscript), and other Cary county maps enhanced by Smith’s 1815 geology, a composite geological map has been made. This map might have resembled a more detailed edition of his great map which Smith could have made were it not for his dire financial situation at the time.

The digital images of maps used in this website have been provided by: The Geological Society, Oxford University Museum of Natural History, National Museum of Wales, Stanford University and Nottingham University.