Royal Dutch Shell owed its origins to Indonesia, formerly known as the Dutch East Indies. Comprising over 17,000 islands, including Sumatra, Sulawesi, Java, and parts of Borneo (Kalimantan) and New Guinea, Indonesia has a long history of oil exploration and development.

On 21 January 2022, Shell officially dropped ‘Royal Dutch’ from its title, following plans to move its headquarters from The Hague to London. It was the end of an era, since the combination of the Royal Dutch and Shell Transport and Trading Company in 1907 had triggered the birth of the global oil company we recognise as Shell Plc today.

The Dutch East Indies

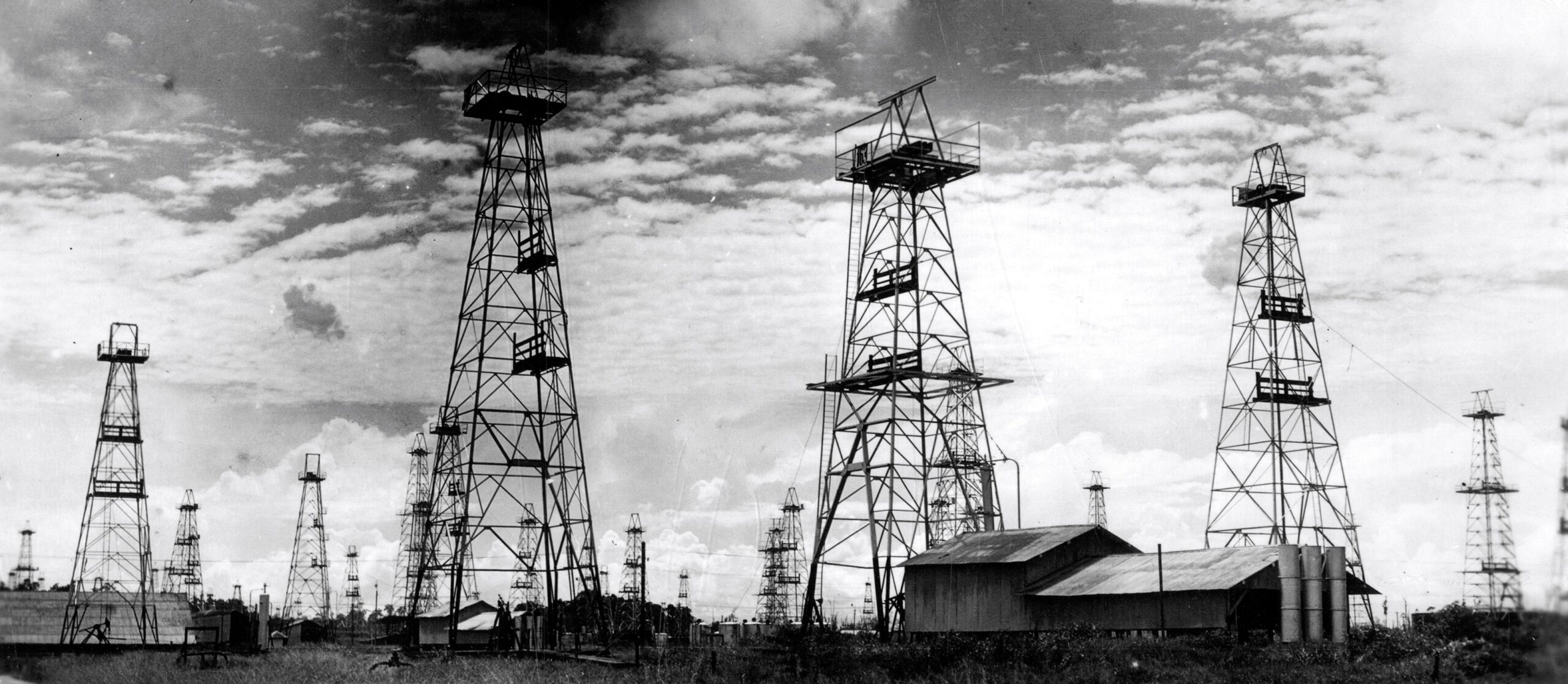

In medieval times, the sight of oil-soaked fireballs raining from the sky as Acehnese fishermen bombarded their enemies was an early indication of the region’s petroleum resources. The modern story of Indonesian oil began in a less dramatic fashion, however, when the Dutch Indies government drilled a modest well in West Java in 1871. The existence of oil seepages and shallow pits was well known by then, and it fell to a 20-year-old tobacco planter named Aeilko Jans Zijklert to start the first commercial venture, a drilling operation powered by mules, in North West Sumatra in 1885. He subsequently struck oil at Telaga Tunggal I in Langkat. This find, together with the discovery of other oil seepages elsewhere in Sumatra, Java and Kalimantan, indicated the region’s petroleum potential.

The death of Zijklert of a tropical disease in 1890 paved the way for the “Royal Dutch Company for the Working of Petroleum Wells in the Dutch-Indies” to continue the development of the Telaga field and build an oil shipping harbour nearby. Despite early disappointments, the new company broadened its scope, constructed a refinery and, in 1898, employed a team of European geologists to survey the wider region.

It seems that the inclusion of ‘Dutch’ in the company’s title was a slip of the pen by the Dutch King’s secretary in signing the company’s royal warrant, rather than a deliberate attempt to bestow nationalistic qualities on the new company. However, its colonial associations were plain enough. The Dutch had established trading posts in Indonesia from the seventeenth century and these came under the rule of the Dutch government in 1800. The area was known to Europeans as the Dutch East Indies and, by 1900, only companies registered in the Netherlands were allowed to operate in there. British commercial interests were represented by the Shell Transport and Trading Company, among others.

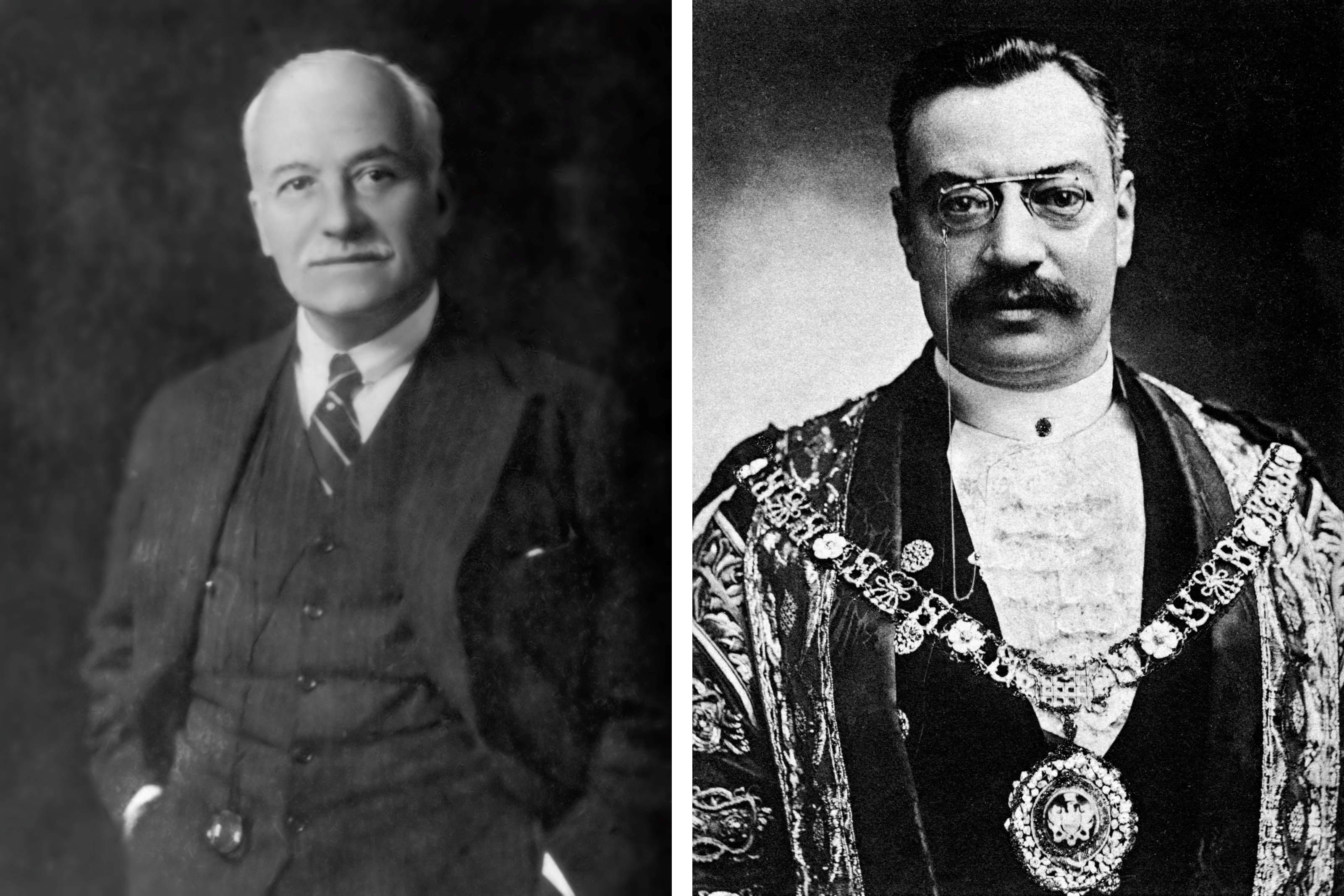

The merger of Royal Dutch and Shell is a story in itself, and has the Rothschild Bank of Paris at its heart. Rothschild engaged Samuel & Co headed by Marcus Samuel to transport their shipments of kerosene from its Caspian oilfields for use as lamp oil in the Far East. Samuel formed the Shell Transport and Trading Company and revolutionized oil transport with a fleet of specially designed ships to carry crude through the Suez Canal; the Murex was the first oil tanker to pass through the canal. Shell also obtained an oil exploration permit for Sangasanga in Eastern Borneo (Kalimantan). Royal Dutch struck its first oil in 1892, shortly before the first consignment of Russian oil arrived in Singapore. Headed by the volatile Henri Deterding, who was determined that his company should rival Rockefeller’s Standard Oil, Royal Dutch soon became a major supplier of kerosene to the Asian market. In 1893, after obtaining the rights to explore Sangasanga, Shell built a refinery at Balikpapan.

Shell’s shipping interests in the Far East brought it into contact with Royal Dutch, and merging was a logical move. As Royal Dutch’s main strength lay in oil production and Shell’s expertise was transport, it would bring together two companies with different but complementary strengths. Indeed, it laid the foundations for the global oil company that became known as Royal Dutch Shell. The following decades saw an impressive phase of worldwide exploration, taking in countries as far afield as Egypt, Romania, Russia, Venezuela, Mexico and the United States.

Shell never forgot its roots, and its distinctive logo – a scallop shell – referencing the time when importing seashells to Europe from the Far East was an important part of its progenitor’s import-export business. The Bataafsche Petroleum Maatschappij (the Batavian Oil Company or BPM for short) was Royal Dutch and Shell’s vehicle for exploring and developing the oil resources of Indonesia with the two companies owning shares in a 60/40 split.

The Rivals

Exploration geologists faced many challenges in the jungles of Indonesia. One tried and trusted method of field work was to follow stream courses inland and examine exposed outcrops along the way. In those areas where oil seepages or favorable structures were present, a track was hacked through the undergrowth and pits were dug to a depth of 15 to 25 feet so that the geologist could clamber down and determine the dip and strike of the strata. Local labourers were employed for this purpose, supervised by young Dutchmen who had grown up in the Indies and were fluent in their language. Dr. Hans Cloos, a German geologist employed to examine concessions in the area, described his frustration at working in the conditions, noting that ‘all the beautiful, rounded, layered domes which we discovered in Java and Borneo turned out to belong to competitors!’

The producing wells were near the Chinese kerosene market, which was most useful when lamp oil was in high demand. The fact that oil from Sumatra was low in sulphur was a boon so far as refining was concerned but, with the advent of the motor car, Indonesian oil was not particularly advantageous because of the presence of aromatics, especially gum. It was only later, in the 1920s, that the value of aromatics in preventing ‘knocking’ in petrol engines was recognised.

A Monopoly

Since Indonesia became one of the largest producers of high-quality crude oil outside the United States, it was inevitable that it should attract the interest of international oil companies, particularly those from the United States. Standard Oil’s interest began in the days when AJ Zijklert was making a name for himself in the Sumatran jungle. But progress was slow – the US State Department was reluctant to become involved in the commercial activities of US companies abroad with the result that Standard was left to fend for itself in its dealings with the Dutch authorities. To meet the requirements of Dutch law, Standard formed a partnership with Moeara Enim, but this broke down after the Dutch minister of colonies questioned the renewal of their five-year concession.

Underlying these events was an anti-Standard sentiment and a desire to keep foreign investment out of the colony. Without US government backing, Standard was destined to support its markets in the Far East from oilfields much farther afield. By 1912, Royal Dutch Shell had virtually secured a monopoly of the Indonesian oilfields when it acquired its last real competitor, the Dordtsche Petroleum Company. By 1920 it controlled about 95 percent of crude oil production and operated oilfields in Borneo, Java and Sumatra, and the Plaju refinery in south Sumatra, which at one time was the largest refinery in South-East Asia.

To comply with the requirement that all companies operating in Indonesia should be registered in the Netherlands, Jersey Standard set up the Dutch-registered and managed NKPM (Nederlandsche Koloniale Petroleum Maatschappij) with its headquarters in The Hague. NKPM applied for an oil concession for the promising Djambi field in central Sumatra, but Royal Dutch Shell intervened and made a higher offer, and then the Dutch authorities suspended all mining operations. For the next five years, NKPM was effectively barred from exploring and drilling for oil. A new Dutch mining law was passed in 1917 which gave the government at least half a share of future oil concessions and enabled it to take over a promising area upon the prospecting company being reimbursed for their expenses.

Oil Running Out?

In 1919, the US Geological Survey estimated that oil supplies would run out in ten years, bringing an oil scare to Washington and a new determination to seek foreign oil concessions which was fanned by a perception that American firms were not receiving equal treatment abroad. In 1920 the Mineral Leasing Act was passed to allow the US government to withdraw the mining rights of foreign companies on home soil if their governments did not allow reciprocal rights to US firms. This was the start of the so-called ‘Open Door’ policy, which represented a push by the US government and firms to gain equal access to commercial opportunities abroad.

In 1921 BPM went into partnership with the Dutch East Indies government and set up Nederlands Indische Aardolie Maatschappij (NIAM) to operate the oilfields around Djambi. In the same year, NKPM discovered oil in the Pendopo/Talang Akar field in South Sumatra, and new discoveries followed. The company built a new refinery and changed its name to the Standard-Vacuum Petroleum Maatschappij or SVPM. In 1934 the company obtained its first concession for central Sumatra and went on to strike oil at several locations.

A late arrival on the scene was the California Texas Oil Company (Caltex) which, as its name suggests, was a merger between Standard Oil of California and the Texas Company. In 1930, Caltex established NPPM (Nederlandsche Pacific Petroleum Maatschappij), also registered in the Netherlands and headquartered in The Hague. Caltex soon struck oil in Central Sumatra and in 1941 discovered the Duri oilfield at a depth of 400 feet. Operations were interrupted by World War II and production did not commence until February 1954. The oilfield measures 10 km by 18 km and is part of the productive Rokan block, which includes the giant Minas field discovered in 1944. The Duri and Minas fields became Indonesia’s most productive fields in the post-war years.

The End of the Colonial Era

By 1938, production had reached 7.4 million tons, all processed by local refineries. But success brought danger. For many years, Dutch officials had suspected that the Japanese coveted the Indonesian oilfields; in fact this was often cited as one of their reasons for excluding foreign oil companies from the area. When war broke out, the oilfields were a primary target for the Japanese, who lacked their own sources of crude and needed vast quantities of petroleum to fuel their war effort. As Japanese forces invaded the Dutch Indies from February 1942, the oil companies set about destroying their installations, but this was only partially successful. Nevertheless, oil production under Japanese control never achieved the same level as during the pre-war years. The Balikpapan refinery, which the Japanese used to supply their navy, was bombed by the Allies, together with other targets. The result was that, by 1945, production had dropped to 845,000 tons.

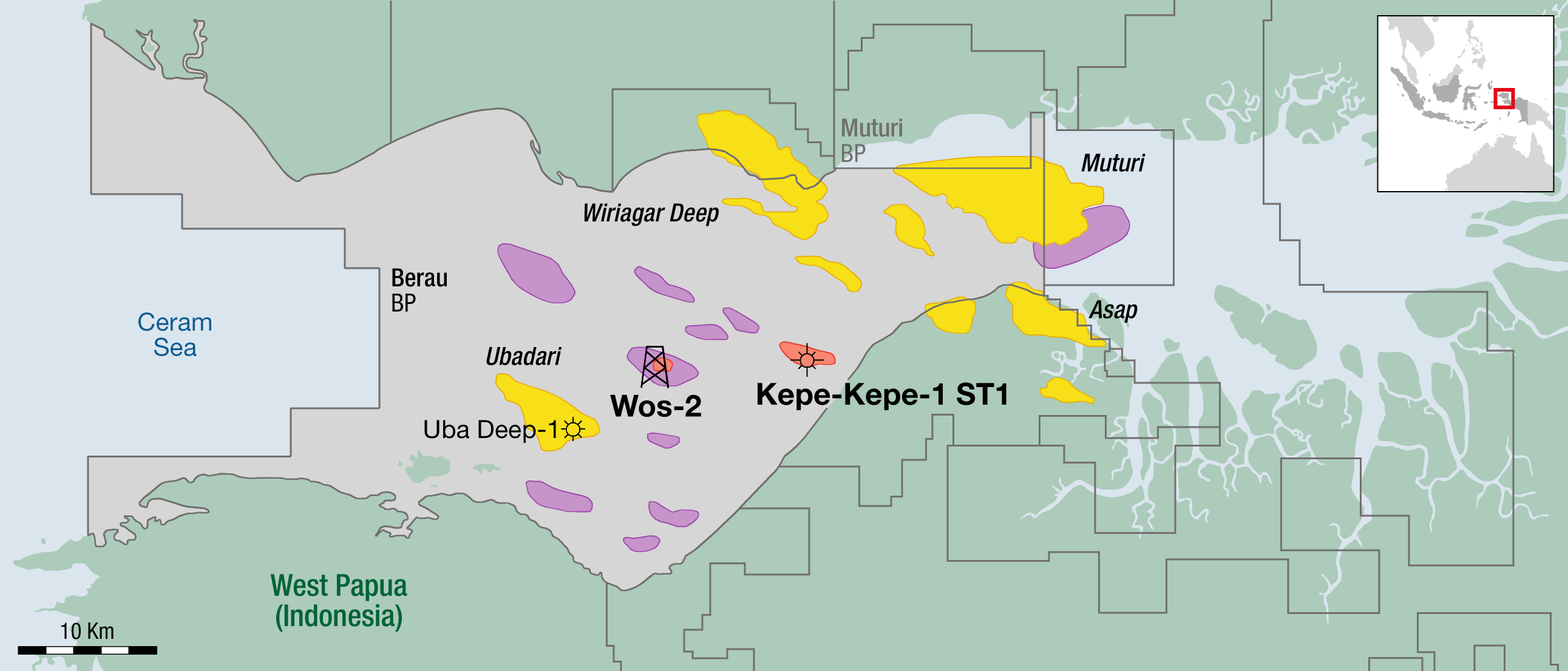

At the end of the war, nationalist leader Sukarno returned to Indonesia from internal exile and declared independence on 17 August 1945, three days after news broke of the Japanese surrender to the Allies, but it was not until 1949 that the Dutch recognised Indonesian sovereignty. The post-war years were characterized by a drive for economic independence and the activities of the state-owned oil company, nowadays known as Pertamina. Nevertheless, ExxonMobil and Chevron (the successor to Caltex) still maintain a presence in the country, being among its main oil producers – Shell withdrew in 1965. In more recent years, declining output has seen Indonesia, which was once among the leading oil producers, dropping to the rank of 25th in the world.

Acknowledgement

Many thanks to Peter Morton for his kind assistance.