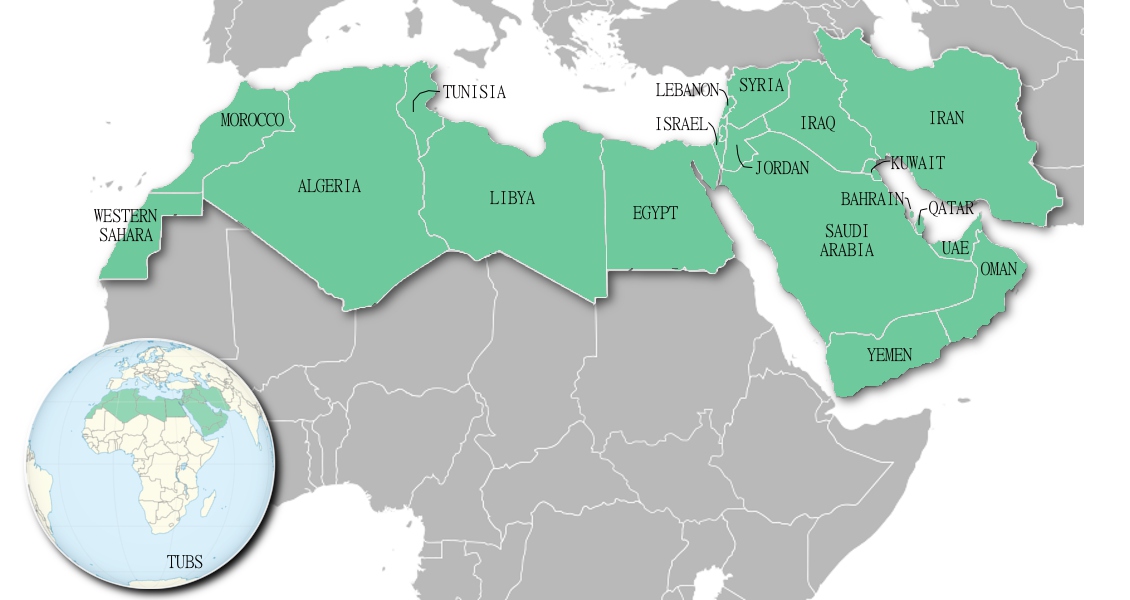

Commentary about the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) may promise an explanation for what is taking place in this intricate region – but often what it offers instead is an excuse for why we cannot explain it and never will. The MENA region is variously described as too complicated (with so many different factors that ‘we’, as outsiders, could never possibly comprehend them) or too simple (fuelled by ancient prejudices like tribe and sect that we could never understand). The implication of both arguments is: give up.

But we cannot give up, because the MENA region’s challenges cannot be contained within its borders and because solving them will take positive contributions – especially trade and investment – to overcome negative stereotypes. And the region can be explained, with the lessons from North Africa being an insightful place to start.

The MENA Region’s Bellwether

The first rule for explaining the region is to not generalise when describing its countries. Borders matter. The Islamic State group (IS) may speak about a Muslim Caliphate, and some commentators still insist on dividing the region into a ‘Sunni’ and ‘Shi’a’ world. But, as important as sectarianism or faith may be at a local level, their impact on geo-politics is often exaggerated. This is still a region defined primarily by states: their governments, their rivalries, and their policies.

Rule number two is that, even though we must not generalise about states, they do face common challenges. They deal with them in different ways.

My view is that the governments of North Africa are caught between two powerful forces and the different responses of Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia, Libya and Egypt will be bellwethers for the rest of the region. One force is that of their people’s aspirations, and the threat of popular unrest if they are not met. The Arab Spring was the beginning of a process that manifested this sentiment, and we can expect it to be manifested yet again. The second force is the need for economic development, to match the aspirations of booming populations at a time of plummeting energy prices.

The outcomes in North Africa will be felt in the wider region and beyond, with Europe in particular either contributing to the region’s prosperity or continuing to feel its pain.

The Drive For Political Stability

Despite the origins of the Arab Spring being in North Africa, the first important trend to identify in the region’s politics for 2016 is that its governments are taking a firmer grip. This is seen in heightened security measures and a more general restoration of law and order, but it also applies to human rights, and the curtailment of free expression.

The controversy surrounding this re-imposition of order should not be taken lightly. The deaths and detentions of anti-government protesters caught the headlines, but the prevention of free political speech and assembly has become pervasive (if less visible) across the whole of North Africa. However, one of the most difficult aspects of this trend to acknowledge is that it has not been universally unpopular.

El Djem in Tunisia is famous for its Roman amphitheater. (Source: Sinead Archer)Among investors, and many ordinary citizens, greater stability has been welcomed despite concerns about the methods through which it was achieved. The energy of the Arab Spring revolutions in North Africa did not simply settle quietly down into the structures of constitutional politics, which were anyway weakly developed across the region after decades of dictatorship. It was also the case that, although the street protesters knew what they were against (‘the regime’), they never articulated what they wanted to replace it with in a unified or specific way.

El Djem in Tunisia is famous for its Roman amphitheater. (Source: Sinead Archer)Among investors, and many ordinary citizens, greater stability has been welcomed despite concerns about the methods through which it was achieved. The energy of the Arab Spring revolutions in North Africa did not simply settle quietly down into the structures of constitutional politics, which were anyway weakly developed across the region after decades of dictatorship. It was also the case that, although the street protesters knew what they were against (‘the regime’), they never articulated what they wanted to replace it with in a unified or specific way.

The result was that free speech and expression in the aftermath of these revolutions became associated with raucous street politics, and efforts to force the adoption of views rather than considering compromise. Libya’s civil conflict began this way, and both Egypt and Tunisia saw blood on their streets. This instability threatened individual livelihoods, the health of the economy at large, and – sparking international attention – could create a space for extremist militancy. Governments therefore imposed stability, but they need to achieve benefits from it soon.

One test in 2016 is whether power can ultimately be shared between those of different persuasions, or if it will be monopolised by those committed to just one. Tunisia’s progress in this respect won it a Nobel Peace Prize, but bitter coalition politics are now giving Tunisians a more unsettling face of democracy. In Egypt, fears that the Muslim Brotherhood would exclude everyone else from power mean that it is now so thoroughly excluded itself as to be illegalised and designated a terrorist group. But Egypt’s Islamists will ultimately need a way of engaging with the state other than through prison. Morocco’s elections, in late 2016, will be another power-sharing test.

But the issue is that the genie of popular aspiration cannot be put back in the bottle for ever. The main political trend to watch in North Africa during 2016 will be efforts by the governments to keep it there, but the main challenge of 2016 will be whether these governments can meet the economic and political aspirations of their youthful and growing populations. If they fail, then no amount of repression will save them from what still remains the greatest risk to state stability in North Africa: popular unrest. Riots relating to economic issues have already occurred in Algeria and Tunisia in 2016, and they won’t be the last that we see this year if stability does not bring prosperity.

Terrorism and its Context

Terrorism is a consequence of state collapse, not a cause. Revolutions may provide space for militant extremism, but the equation cannot be reversed. But it is terrorism above all else that will draw international attention to North Africa, and consume the energy of the governments in this part of the world. The coming year will be characterised by efforts to solve the conflicts and failures of governance that give rise to terrorism, with the peace process in Libya and counter-insurgency in the Sinai being the key test cases.

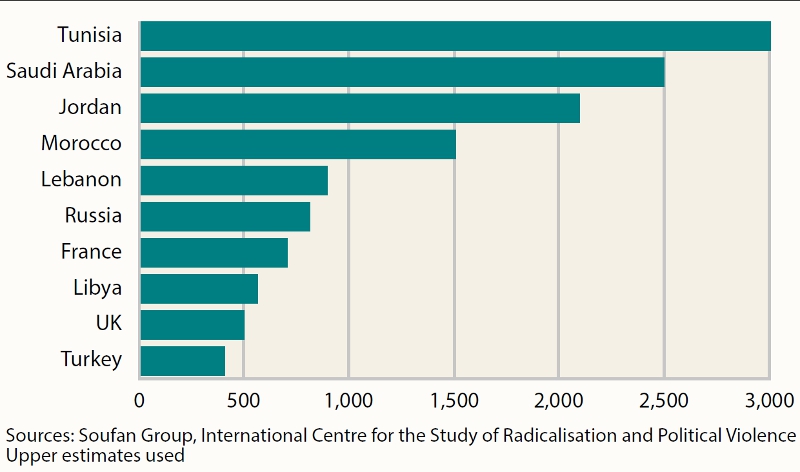

Foreign fighters in Syria and Iraq.The rise of the Islamic State group (IS) does, in this context, seem to constitute an evolution of jihadism into an even less pragmatic and more pernicious form. Its desire to hold territory, and its determination to kill all who will not obey it, means that even Al-Qa’ida’s members are among those who detest and fight IS. But there are encouraging signs to look for in 2016, when it comes to countering IS and other militant groups in the region.

Foreign fighters in Syria and Iraq.The rise of the Islamic State group (IS) does, in this context, seem to constitute an evolution of jihadism into an even less pragmatic and more pernicious form. Its desire to hold territory, and its determination to kill all who will not obey it, means that even Al-Qa’ida’s members are among those who detest and fight IS. But there are encouraging signs to look for in 2016, when it comes to countering IS and other militant groups in the region.

The first is that the zealotry and lack of pragmatism displayed by IS may alienate the group from its local social base. Its emphasis on foreign fighters could be one of the group’s weaknesses in this respect. Its lurid atrocities against locals are another.

If IS continues to alienate local communities in 2016, such as it will in the Sinai if it remains determined to disrupt the tourist trade on which they depend, then the self-destructive impetus in IS’ brutality and lack of long-term strategy will become apparent. Menas consultants report that a conspiracy theory is already gaining credence in the region that IS is a Western plot to undermine Muslims and, as derogatory as that may be, it could at least serve to discredit the image of a terrorist group that relies on presentation for effect.

A second factor in 2016 will see not only efforts to attack terrorist groups militarily, but also a recognition that this will not work without redressing the context in which they operate. If these terrorist groups seek to take and hold territory, like IS does, then they cannot be defeated by airstrikes: 2016 will see greater efforts to confront them on the ground. If they emerged from civil conflicts, then they cannot be defeated until that conflict is resolved: Libya is the key test case here, as its war has exported terrorism into North Africa. The year 2016 will test the emphasis that the international community has placed on Libya’s new unity government to solve that conflict.

But terrorism is where political, economic and security failures converge. Governments need to counter terrorism militarily, while also offering their people positive and compelling economic or political reasons to not join such groups. If the political scale is being tilted towards greater control rather than openness in the region, then the economic stakes will become higher still.

Economy Remains Key Battle

The future political and security stability of North Africa will ultimately depend on its economies; whether they can address the abundant poverty that exists throughout the region and still create enough jobs to sustain a youthful and growing population.

Commerce is key, but North African states look more to Europe than one another for trade. (Source: Jane Whaley)North Africa is one of the world’s least economically integrated regions, and an effective start could be made in 2016 by facilitating trade between states. But the impetus so far has been for these countries to further fortify themselves, building more fences and berms and deploying more troops to their borders as a response to the focus on militancy. Smuggling may be thriving, but licit trade is not, and that is not a problem that is likely to be solved quickly as national road and rail networks are so poorly connected across their international boundaries and there is no apparent political will to redress this. North African states still look to Europe for trade, not each other.

Commerce is key, but North African states look more to Europe than one another for trade. (Source: Jane Whaley)North Africa is one of the world’s least economically integrated regions, and an effective start could be made in 2016 by facilitating trade between states. But the impetus so far has been for these countries to further fortify themselves, building more fences and berms and deploying more troops to their borders as a response to the focus on militancy. Smuggling may be thriving, but licit trade is not, and that is not a problem that is likely to be solved quickly as national road and rail networks are so poorly connected across their international boundaries and there is no apparent political will to redress this. North African states still look to Europe for trade, not each other.

Then there is the issue of the collapse in energy prices, and the reality that – if they stay low for a number of years – states such as Algeria that have become dependent on oil and gas revenues for their state budgets (and generous welfare provisions for their millions of poorer citizens) will be at serious risk of unrest. Algeria is stressing the merits of diversification, while Egypt has emphasised that it wants to use its expanding energy reserves to address booming domestic demand rather than prioritising export. But these are long-term solutions to immediate problems, and time may not be on the side of nervous governments or their restless citizens.

The upshot is that there will be an abundance of investment opportunities in North Africa during 2016, and evolving terms on which business can be conducted. Governments will be eager to attract investment, particularly that which allows them to boost local employment and reduce reliance on imports, while at the same time competing more intensely with one another to do so.

The demand for business is certainly there, as are the opportunities. The ambiguity lies in the environment. There will, in the short term, be a period of greater calm in North Africa as populations remain reluctant to rebel, eager to draw prosperity from stability. The fear of terrorism will always remain greater than the threat, even though that threat will persist. But this window of opportunity must be used to attract trade and investment, and improve the effectiveness of governance. Whether it succeeds or fails, North Africa in 2016 will give us an abundance of signs to look out for.