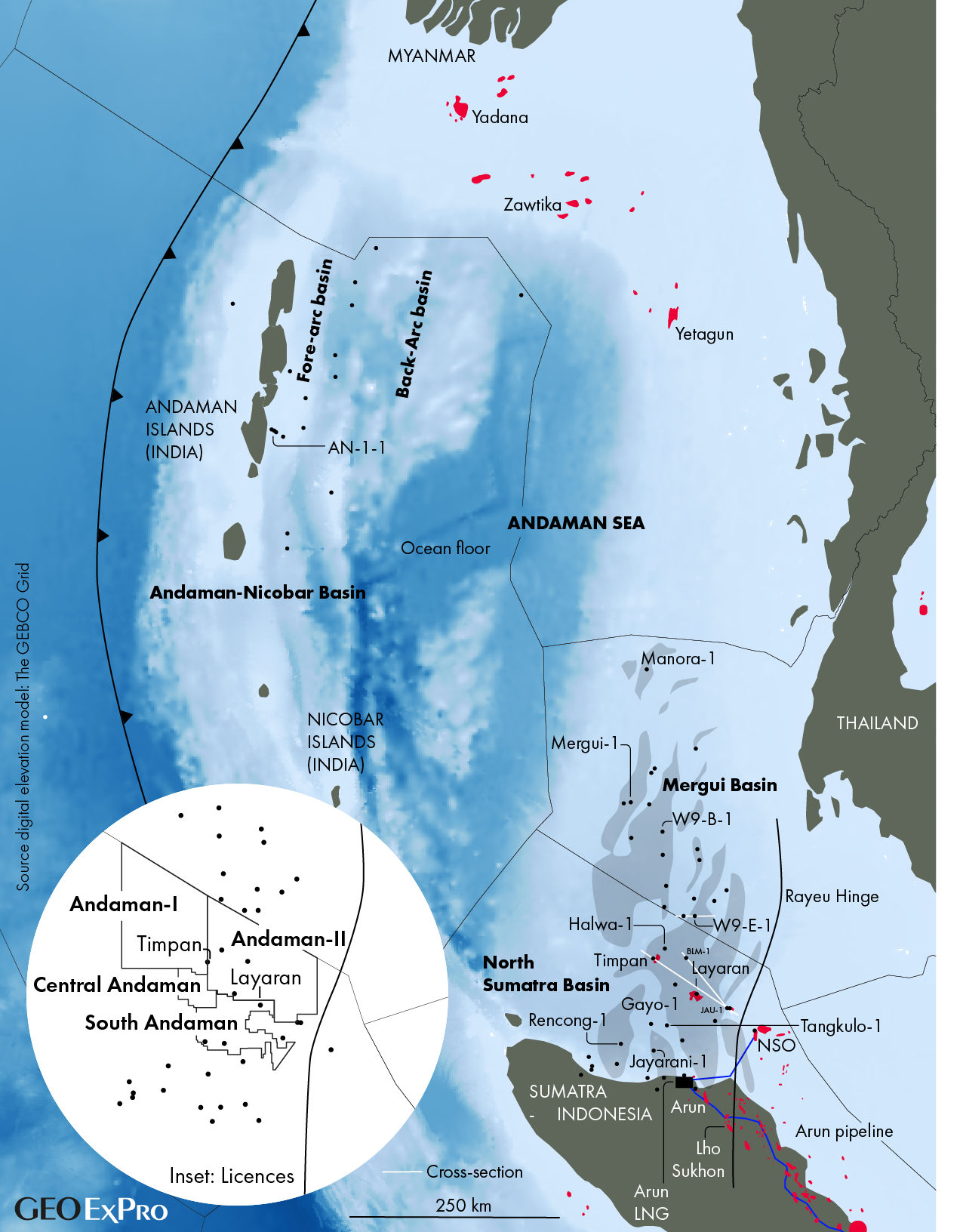

Before taking a dive into the past, recent and future exploration activity in the Andaman Sea, it is good to take note of an important above-ground advantage of the area. There are no country boundary conflicts. This is not because the entire Andaman Sea territory is claimed by a single country; there are four: Myanmar in the north, the Indian Andamans Islands towards the west, Thailand in the center and Indonesia in the south. This saves the area from major issues that other parts of SE Asia face, for instance, the nearby Thai-Cambodia Overlapping Claim Area.

Before taking a dive into the past, recent and future exploration activity in the Andaman Sea, it is good to take note of an important above-ground advantage of the area. There are no country boundary conflicts. This is not because the entire Andaman Sea territory is claimed by a single country; there are four: Myanmar in the north, the Indian Andamans Islands towards the west, Thailand in the center and Indonesia in the south. This saves the area from major issues that other parts of SE Asia face, for instance, the nearby Thai-Cambodia Overlapping Claim Area.

The basin has a rich history of petroleum exploration, with Myanmar and Indonesia being more successful and Thailand and the Indian Andaman sector yet to celebrate their first commercial discovery. Despite the lack of commercial success in the latter two areas, the region is currently undergoing a renewed phase of interest following the announcement of the Tcf-sized Timpan discovery in the deep-water area of the North Sumatra Basin in early 2023, followed by the more recent Layaran-1 and Tangkulo-1 gas and associated condensate discoveries in the same area and play. This may encourage India to drill new wells near the Andaman Islands, with one of them currently operating, even though the geological setting is very different. It may also generate renewed enthusiasm in the Thai part of the geologically similar Mergui Basin.

What follows below is a brief overview of the Andaman Sea’s petroleum geology, exploration history and future drilling plans. Most of the input is from Andy Racey and Andy Taylor, who have recently finished an extensive non-proprietary report on the petroleum geology of the southern Andaman Sea. This is supplemented with thoughts provided by Ian Cross and Mike Whibley. Finally, Rob Chambers provides some thoughts on how the recent discoveries around Timpan could be developed.

Since the recent exploration successes are solely in the south of the Andaman Sea, the focus of this article lies in the Indonesian and Thai parts of the basin.

Geological setting

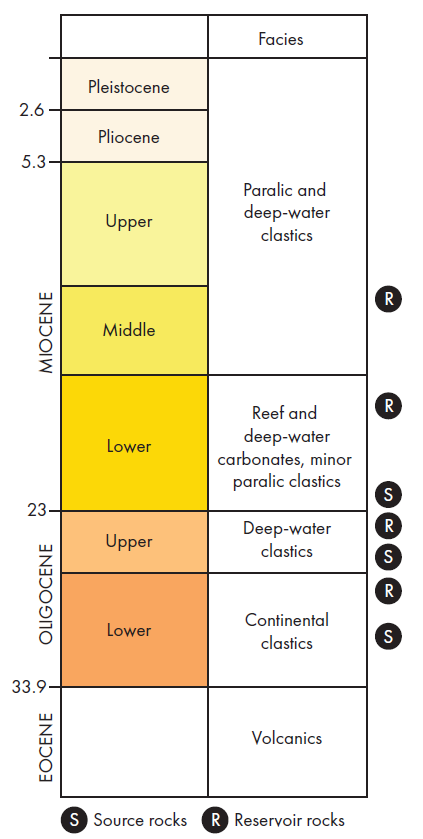

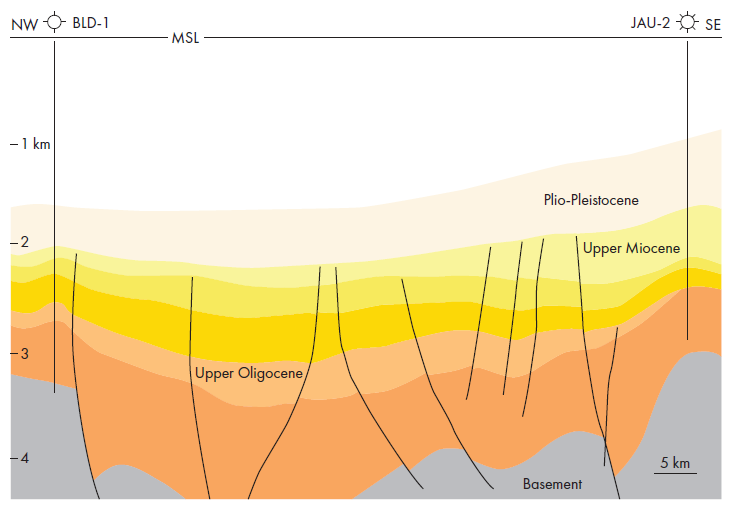

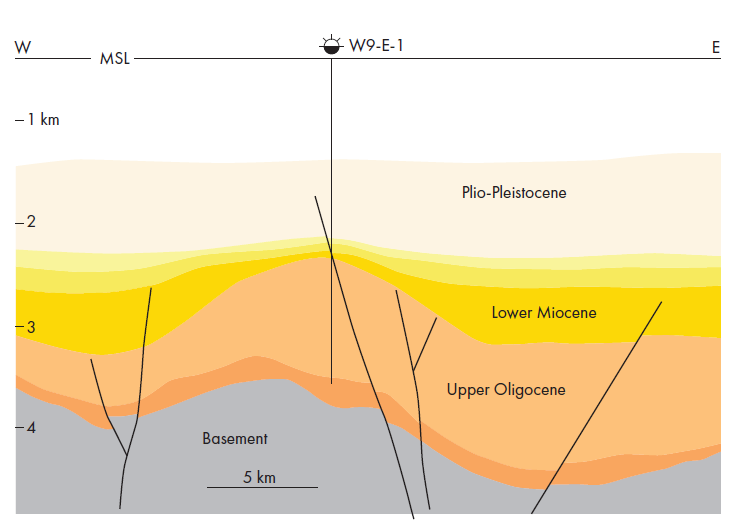

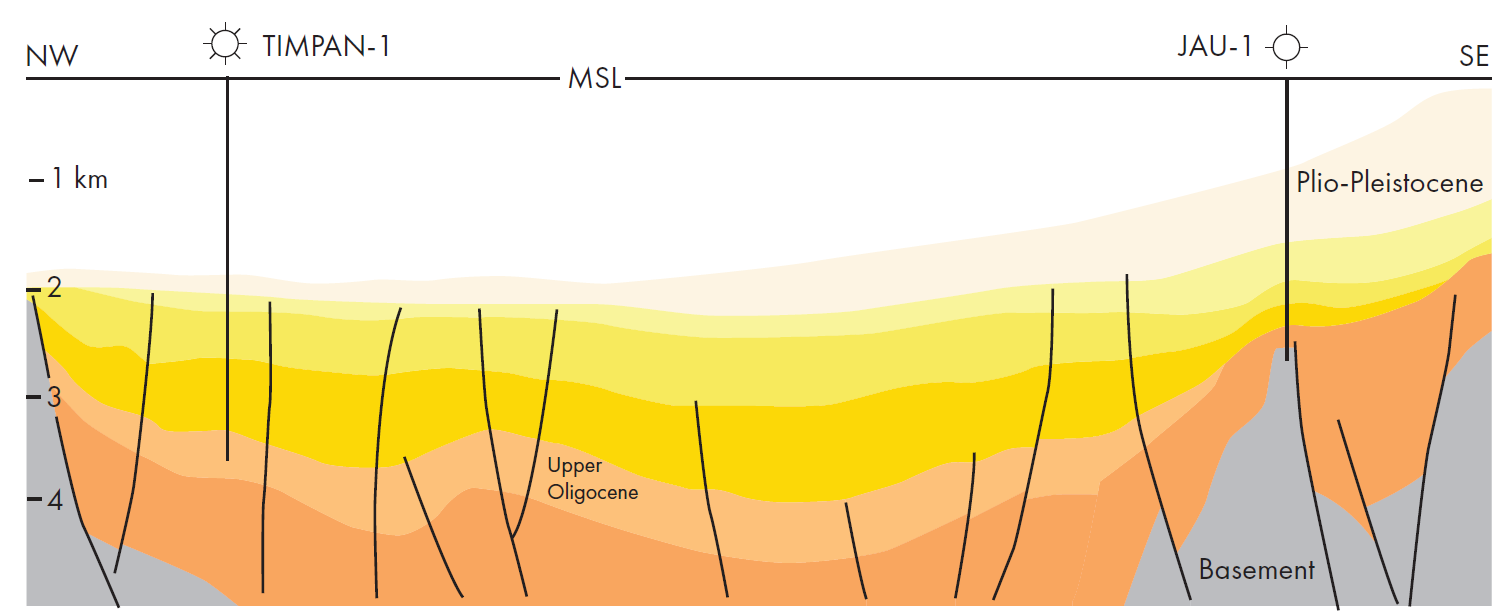

The North Sumatra-Mergui Basin, which forms the southern Andaman Basin, is often referred to as a back-arc basin but is really developed in a dynamic transtensional tectonic setting. The onset of rifting started in the Late Eocene with associated volcanics and was followed by the deposition of a Lower Oligocene continental early syn-rift sequence. A major transgression in the Late Oligocene established the widespread late syn-rift deep marine clastic sequence. The Early Miocene subsequently marked the onset of inversion and regression with the deposition of shallow and deep marine carbonates. The Middle Miocene starts with renewed transgression and deposition of mixed shallow and deep marine clastic sequences. Subsequently, the uplift of the Barisan Mountains to the south in onshore Sumatra initiated the rapid deposition of a thick sequence of Upper Miocene to Pliocene aged marine clastic sediments.

Drilling history

Drilling in the Andaman Sea area has been most prevalent in Myanmar and Indonesia. However, the first reports of oil and gas exploration in the Andaman Sea were in the late 1950s, when the Indian national oil company, ONGC, undertook surveying and mapping.

Approximately 112 wells were drilled offshore Myanmar, resulting in three producing gas fields in three different plays; Yadana, Zawtika and Yetagun.

In both the Indian and Thai sectors, nineteen wells have been drilled in each so far. India’s first exploration well, AN-I-I, was drilled in 1980 and was a small gas discovery, with another four wells reporting gas shows. In the Thai Mergui Basin, two untested gas discoveries were made with gas shows reported in a further five wells.

Drilling in the North Sumatra Basin resulted in the discovery of the giant Arun gas field onshore with around 14 % CO2 and the Lho Sukhon and North Sumatra Offshore (NSO) fields, all within Lower Miocene carbonate reservoirs.

In the northern part of the North Sumatra Basin, most of the large tested traps are stratigraphic and include Lower Miocene reefs on structural highs such as the Arun and Lho Sukon fields. Sandstone pinch-outs and drapes over structural highs and roll-over structures associated with growth faults and shale diapirs have also been tested. It has previously been assumed that vertical migration is required, and therefore, many of the structures drilled to date have been located on highs close to large faults, which are assumed to tap into the inferred deeper source kitchens.

Prior to the recent phase of exploration activity, around 20 wells had been drilled in the offshore North Sumatra Basin, west of the Rayeu Hinge, resulting in four minor gas discoveries, one small oil and condensate discovery and four wells with gas shows in an area of around 60,000 km2. The addition of the three large recent discoveries, plus two with gas shows, markedly improves the exploration success rate and the estimated ultimately recoverable resources for the basin.

North Sumatra Basin recent exploration

Where legacy exploration in the North Sumatra Basin previously mainly focused on Miocene reefs, more recent exploration efforts have targeted the Upper Oligocene Bampo Formation turbidite sandstones with a reported gross potential of 12 Tcf gas and 400 MMbbls condensate. This did not come out of the blue; flat spots had been observed in 2D seismic lines across the area for a long time, but the deep-water nature and the risk of elevated CO2 levels, such as observed onshore Sumatra, delayed their drilling.

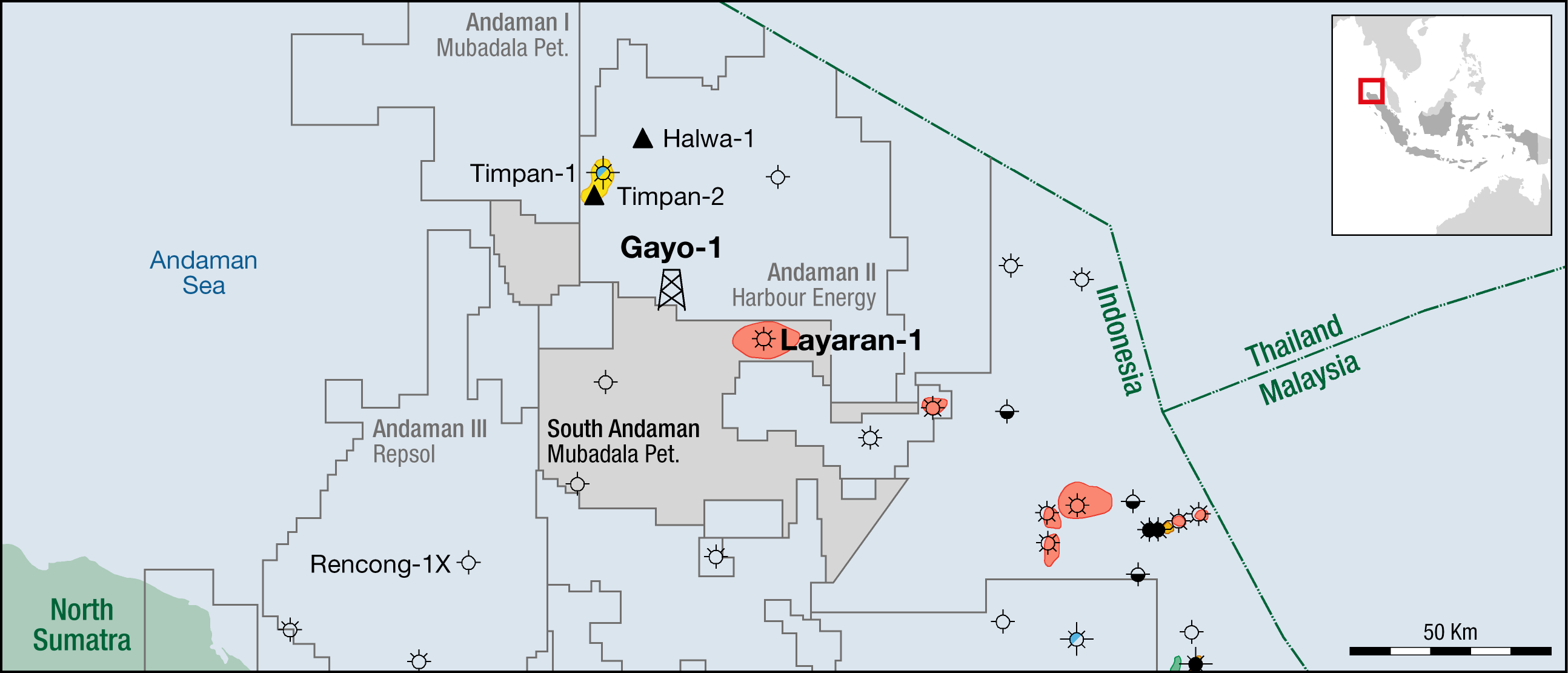

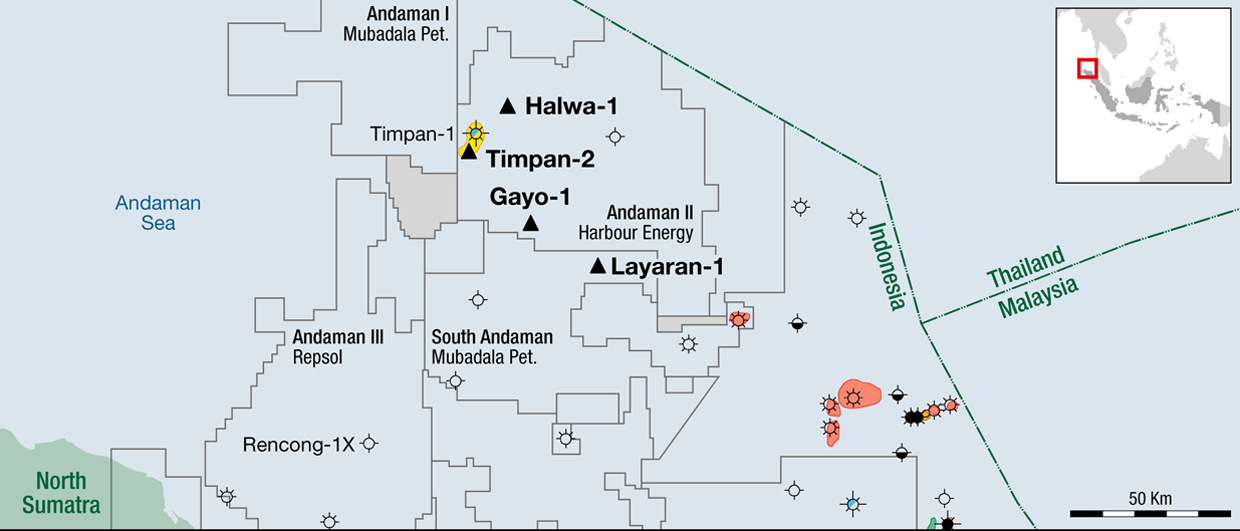

Timpan-1 was ultimately drilled in July 2022, and because of the associated flat spot it was considered by Harbour to be an “appraisal well” with a 70 % chance of success. Indeed, the well encountered a 119 m gas column and flowed at 27 MMscfgd and 1884 bpd of condensate and represents a 1.4 Tcf discovery. The reservoir comprises high net / gross fine-grained sandstones.

The much-awaited Ren-cong-1X wildcat was spudded just before Timpan-1 in the Andaman Block III PSC. The main play in this PSC, originally awarded to Talisman in 2009, was considered to be Upper Eocene to Oligocene carbonate build-ups. However, the well came in dry, which caused Repsol and PETRONAS to exit the North Sumatra Basin in August 2023.

The second well on the same clastic turbidite play as Timpan was Layaran-1, which encountered a 230 m gas column in the same sandstones that flowed gas at 30 MMscfd and is estimated to have a GIIP of 6 Tcf.

The third well, Gayo-1, identified a good gas column at the same level but of poorer reservoir quality. Subsequently, Halwa-1 encountered only gas shows but had good reservoir quality. At the Halwa-1 location, a fault runs from the target reservoir almost to seabed, where a bright spot can be seen in the seismic. The main risk was, therefore, around the presence of commercial quantities of gas deeper down, which now seems was not the case with trap breaching being the main potential issue. The most recent well, Tangkulo-1 drilled in the Andaman South licence, flowed 47 MMscfgd and 1,300 bcpd.

These recent exploration results indicate that the concerns about CO2 were unfounded, but reservoir quality, especially permeability and chlorite cementation, remains an area of concern. Based on trends in reservoir quality, it now appears that reservoir quality could get better in a westerly direction.

Further wells are planned over the next few years.

Mergui Basin exploration

Adjoining and contiguous with the North Sumatra basin to the north is the offshore Mergui Basin in Thai waters, which has an areal extent of around 50,000 km2.

Exploration activities in the Mergui Basin is broadly divisible into two phases. From 1974 to 1979 Esso and Unocal acquired 2D seismic data and drilled 10 wells, resulting in two untested gas discoveries (W9-B-1 and Mergui-1). Esso drilled five wells in 1975 – 1976, while Unocal drilled a similar number around the same time.

From 1983 to 2000, additional seismic data were acquired and nine further wells were drilled, three by Placid Oil in 1987, five slim-hole (mostly shallow) wells by Unocal in 1997 and one well by Kerr McGee in 2000 (Manora-1), which was the last one to be drilled in the Thai sector of the Andaman Sea. The Manora-1 well was a commitment well, and because Kerr McGee was keen on exiting the basin, rumour has it that the Manora prospect was selected quite haphazardly.

The main play tested to date in the Mergui Basin is similar to that seen in the North Sumatra Basin and assumes the presence of Oligocene Ranong Formation source rock in the grabens charging Miocene carbonates and clastics on basement highs sealed by younger mudstones. None of the wells drilled in the Thai sector reported any CO2 associated with the gas.

Remaining hydrocarbon potential is likely to be limited to deeper water (>1 km) areas closer to the main thermally mature depocentres, with gas the most likely hydrocarbon type and source potential and charge effectiveness being the principal risks. The recent discoveries on the Indonesian side of the border suggests that the current geological model needs revising in terms of reservoir type and distribution.

The Mergui Basin is currently unlicensed with no exploration activity since 2000. Speculative non-proprietary seismic surveys are not allowed in Thailand, which limits the chances for the acquisition of new multiclient data. However, it is understood that PTTEP shot some newer proprietary 2D lines recently in the East Andaman Basin.

Myanmar and India

Further north, in Myanmar, three main proven plays exist. In the Yadana field, thermogenic gas is produced from Lower Miocene shallow marine carbonates; biogenic gas is produced from Plio-Pleistocene shallow marine deltaic sandstones in the Zawtika Field – related to Ayeyarwaddy delta coming from the north – and thermogenic gas with condensate is produced from shallow marine sandstones shed from the peninsula to the east of the Yetagun Field. To the west of the Andamans, along the Rakhine coast, biogenic gas is produced from Pliocene sandstones in the Shwe / Mya complex of fields. Western companies have mainly pulled out of Myanmar because of the political situation.

The Indian sector of the Andaman Sea is characterised by a very different geological setting compared to Indonesia and Myanmar, as it sits mainly in the fore-arc basin of the Indian plate accretionary system and is impacted by distal sediment input from the Ganges-Brahamputra and Ayerawaddy deltas to the north.

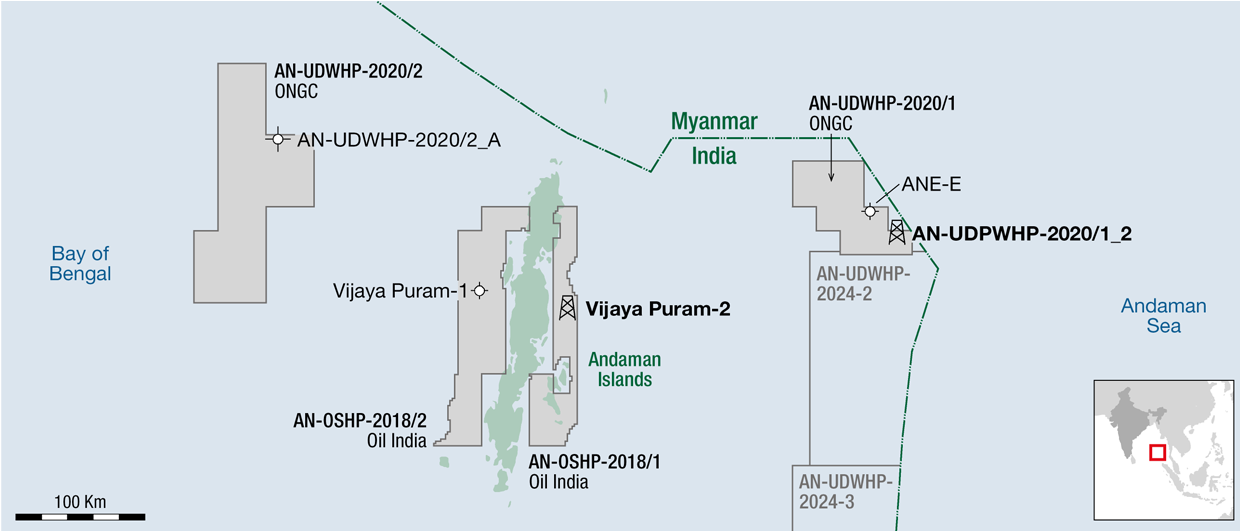

As mentioned above, 19 wells have already been drilled in the past, but Oil India recently announced that it will spud three more, with one already drilling as we go to print Mid-February. There is limited further detail available, but the team at Westwood anticipates that the most likely prospects are Paleocene to Oligocene deep marine sands deposited in the accretionary wedge. Miocene carbonates on the highs could be another target.

In addition, Westwood also anticipates one deep-water well for ONGC in the Andaman Back-Arc basin, just south of Myanmar territorial waters, that will likely target plays similar to the syn-rift Lower-Middle Miocene clastics of the Yetagun Field, or the post-rift Upper Miocene-Pliocene deep marine clastics of the Zawtika field.

Development scenarios for the recent gas discoveries around Timpan

The Andaman Sea has long been discussed as a frontier area with potential, and there will be companies looking at the recent success and asking, “Why weren’t we part of this?” and “Can we be part of this now?”.

Mubadala and Harbour are the main incumbents, holding the majority of the current Andaman acreage. We saw both companies further cement their presence by signing a PSC last year with the Indonesian government for the Central Andaman work area. This work area covers acreage previously relinquished from the South Andaman PSC. bp is the other company currently involved, with a 30 % stake in the Andaman-II PSC that they acquired from KrisEnergy in 2019.

One potential way for a company to enter the area is through M&A. Either of, or both, Mubadala and Harbour could look to dilute their interests, especially if the new partners bring deepwater and LNG experience. For bp, they could look to be central to any development, or they may look to exit for a nice profit.

Another option for entry would be the acreage previously covered by the Andaman-III PSC. This was relinquished by Repsol and PETRONAS in August 2023 following the drilling of the Rencong-1 exploration well that came up dry. For this option, we will need to see how SKK Migas offers this acreage.

Given the potential scale of the development, there will inevitably be political interest, with one of the remaining issues being the end market(s) for the gas. Indonesia would like as much of the gas as possible for the domestic market, but the current infrastructure is limited. The Arun pipeline that could carry the gas south into Central Sumatra is understood to have a current capacity of about 300 MMscf per day. Other options for pipe gas include Singapore or Malaysia, with both countries likely to show an interest given rising domestic demand and high LNG prices.

Another option would be LNG, which may offer access to better prices. There is existing LNG infrastructure at Arun in North Sumatra. However, the plant has been mothballed for a number of years and is unlikely to be easy (or cheap) to reactivate. Other LNG options could include a new onshore LNG plant or and offshore LNG vessel (FLNG) could also be considered.

As hinted at above, domestic gas pricing is another challenge for the development, with Indonesia wanting to cap gas prices for industrial use at $ 6 to 6.5 per MMbtu. This means that Harbour and Mubadala are likely to be keen to export as much of the gas as possible given the higher price point that could be achieved.

We may see an eventual development based on a compromise, with both domestic gas commitments through the existing Arun pipeline and LNG exports. Whilst this works on paper, the details will need to be ironed out and, as we have seen elsewhere in Indonesia, this is not always a simple or quick process.

If FID was taken today, we could see first gas as early as 2028 / 2029. However, as we have seen, there are plenty of issues that need to be resolved before FID. In addition, Mubadala and Harbour may look to further appraise the discoveries or drill further nearby prospects. Given all of these factors, a more realistic target for first gas would be 2030 – 2032.