When I was a PhD student, 20 years ago, a seasoned geologist told me that the energy transition was not so much a transition, but a shift towards tapping into all possible sources of energy in the light of oil and gas becoming more difficult to produce. The Chinese took to heart what my manager said at the time.

They are clearly at it. Whilst building new coal power plants all the time, the country also champions the solar, wind and hydro sectors. Nuclear energy has also seen a spectacular rise, especially between 2010 and 2020, with 30 more power plants under construction.

That is not enough, though. If any nation is pushing the frontiers of oil and gas exploration, it is China. Abroad, they are present in an increasing number of places, with Suriname being one of the latest countries to sign a Production Sharing Agreement. In the meantime, they keep on drilling away in many other areas, amongst others in the Congo, where I heard it is not uncommon to see the completion of 200 wells within a year.

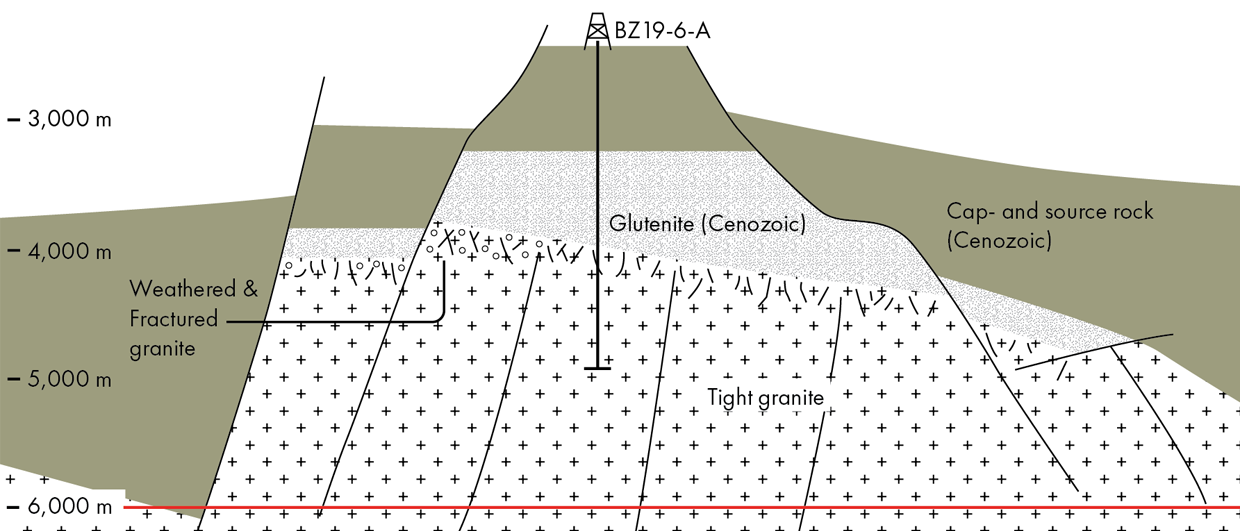

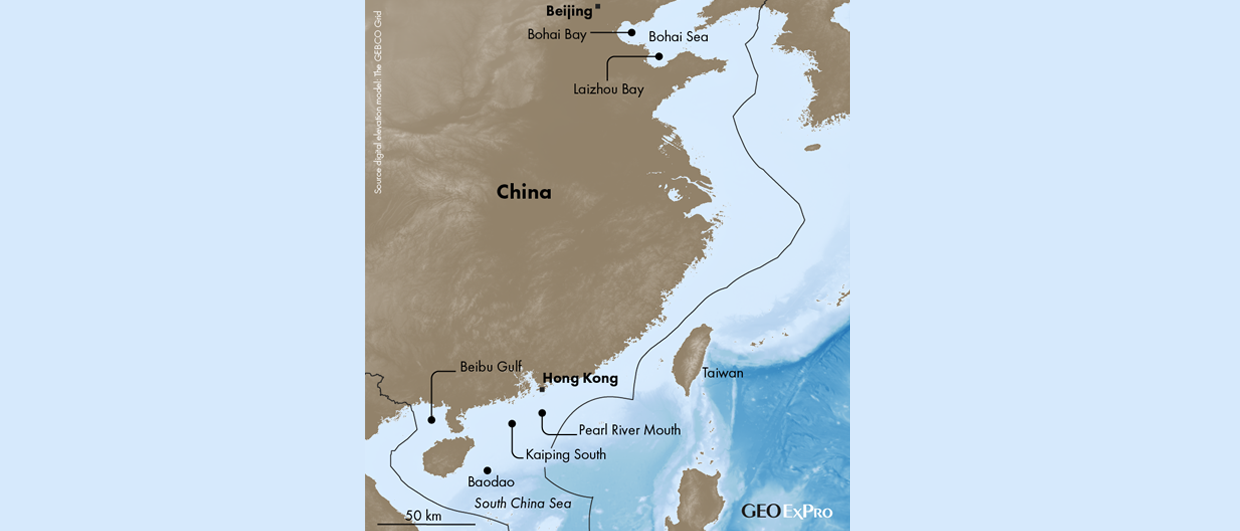

And then on home turf, the quest for new hydrocarbon resources continues, with ultra-deep exploration in the Tarim Basin, development of basement reservoirs in the Bohai Sea, and now the reported find of ultra-shallow gas in ultra-deep waters. So, what is this about?

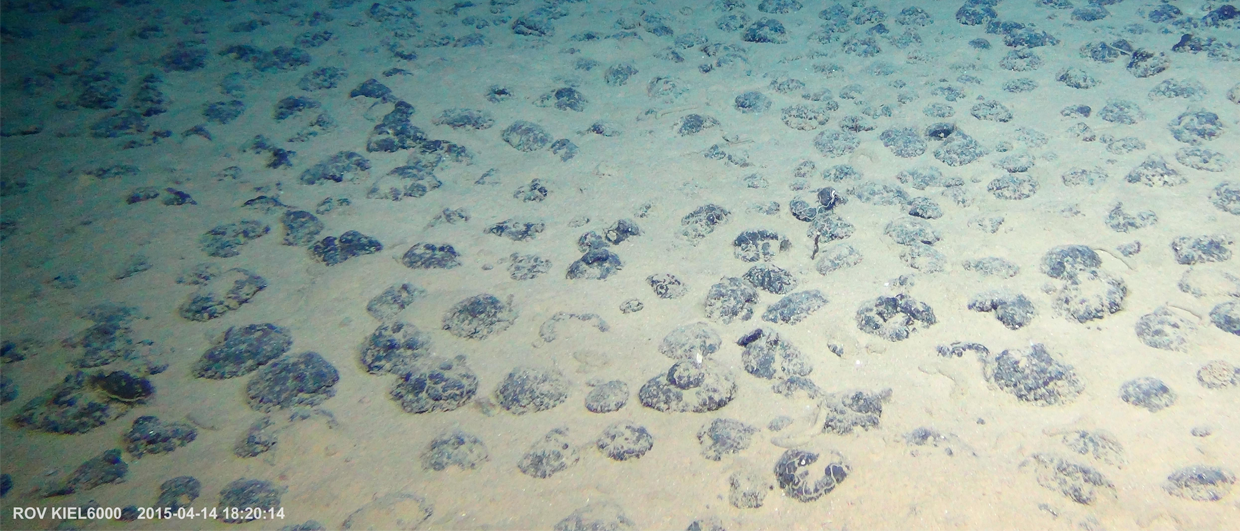

The discovery was announced by CNOOC in June and says that the Lingshui 36-1 gas field – situated in the South China Sea – is in approximately 1,500 m of water but only 210 m below the seabed. The reservoir is of Quaternary age, and it seems to have a gas-in-place volume in excess of 100 billion cubic meters.

In contrast to the West, where one won’t find any literature on a new discovery in the public domain, this is different in China. The Journal of Marine and Petroleum Geology already published a paper last year on what is supposed to be the area where the discovery was made, clearly suggesting that the timing of the press release does not line up with the moment the well reached TD.

One of the main conclusions of the paper is that the gas could be trapped at such a shallow depth below the seafloor because of the high water depth, the resulting pressure exerted by the water column, and the presence of gas hydrates. That is a very interesting observation, as it deviates from the commonly held view that most shallow gas in marine environments is sub-economic because of a lack of effective trapping. Have the Chinese hereby unlocked a new type of play? As they report in the paper, this model of shallow gas in deep waters may be a play worth looking at in other parts of the world too.