While people in Bolivia easily spend two days queuing up at fuel stations these days – the country has very quickly turned from an exporter to a net importer of energy in recent years – the electric cars in Norway zoom smoothly over the neatly gritted tarmac. Energy security is not very much on people’s minds in the Nordic country, I think.

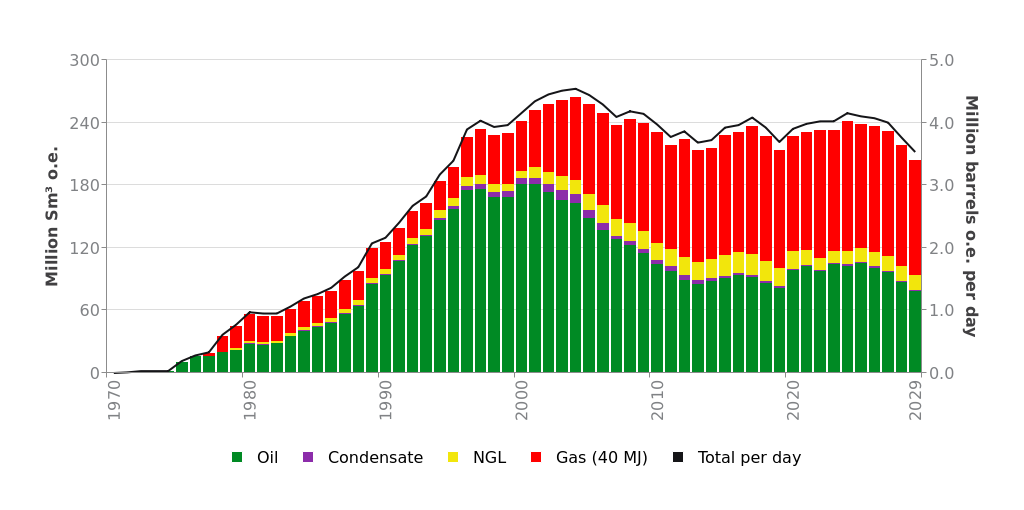

But even in a place that has now enjoyed an energy surplus for decades, some industry people are getting increasingly nervous about what seems to be an inevitable turning point; the start of decline in oil and gas production in Norway. According to most projections, that is going to happen within the next five years. Norway currently produces a bit more than 4 MMboe per day.

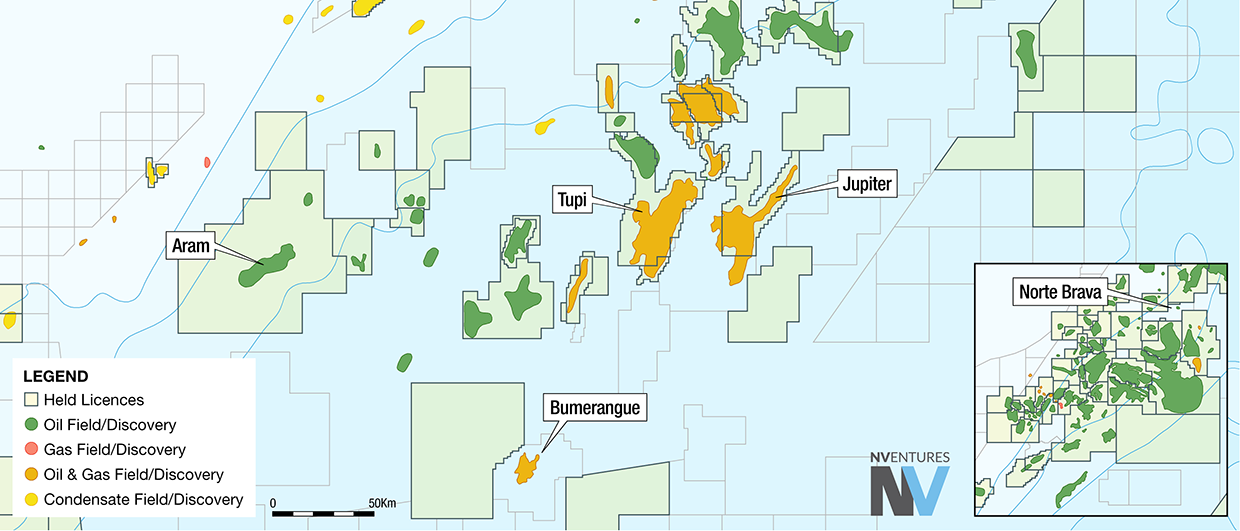

And if you look at what has been found over the past decade, there is little hope that the reserve replacement ratio will climb to a level where more volumes are discovered than what is produced. Exploration has strongly focused on near-field drilling, which, even though profitable and highly efficient when it comes to extending the life of receiving hubs, does little to arrest the overall decline in the country’s hydrocarbon production.

The number of operators available to explore the shelf is also at a historic low of around 20. One of the main reasons for this is mergers and acquisitions. As most companies have a drive to grow production, it is getting increasingly hard to make that happen through the drill bit. The only solution left is to acquire or merge with other explorers. Vår’s acquisition of Neptune is an example, as well as Harbour’s purchase of Winterhall’s assets. The list of transactions is long.

Against this backdrop of the approaching decline, there are still some inefficiencies in what looks like such a smoothly-run and transparent society to an outsider like me. For example, the time to develop a new discovery in Norway tends to take twice as long as in the GOM. Listening between the lines at the conference, a lack of concrete development plans at the time of drilling is one of the reasons for this delay. Over-engineering is another. As someone with direct knowledge of the NCS told me during a coffee break; “I remember a case in which an operator came up with a plan to develop a 40 million barrel prospect with 14 development wells.” Oil prices must be very high to justify such an investment.

Another hurdle that was voiced during the conference is about the lack of communications between oil companies. To make a call on what the best export route for a new discovery should be, the operator of a new discovery needs to know the capacity of the pipelines. It is that information that is not always directly shared by the owners of the hubs, which is detrimental to making a well-informed decision.

Aker BP and DNO now aim to break with this trend of sluggish development, and have been very vocal in local media that they aim for first oil from the recent Kjøttkake (meat balls) discovery in three years. Apart from the intrinsic desire to have first oil as soon as possible, I also feel that this is a little prod to Equinor who still have to come up with an overall development plan to hook up their operated discoveries in the same area.

So, companies are increasingly aware of the sense of urgency to work towards arresting the coming decline. Looking at drilling plans and taking into account the clear lack of frontier exploration successes reported over the past few years though, it looks like Norway will ultimately come off plateau in the next few years. I hope Brussels is listening.