When porosities and fluid contrasts are modest, the acoustic impedance (AI) changes associated with water sweeping oil can be small, even at relatively shallow depths. That is the case in the Golden Eagle field in the UK North Sea, where the change in AI from baseline to repeat survey is only 3 % at best. In order to detect any 4D signal in an oil field with such a subtle response, the quality of the seismic data must be exceptional.

As Andrew Wilson from operator CNOOC International presented at the Seismic Conference in Aberdeen in May 2025, the high-density retrievable OBN surveys acquired over Golden Eagle have met these high-quality criteria. With a ratio of 3D signal to time-lapse noise of 25, it is one of the best in class, delivering quality as good as many permanently-installed ocean bottom seismic systems, but at much lower cost.

Making sense of the 4D seismic signal from Golden Eagle came with some interesting insights.

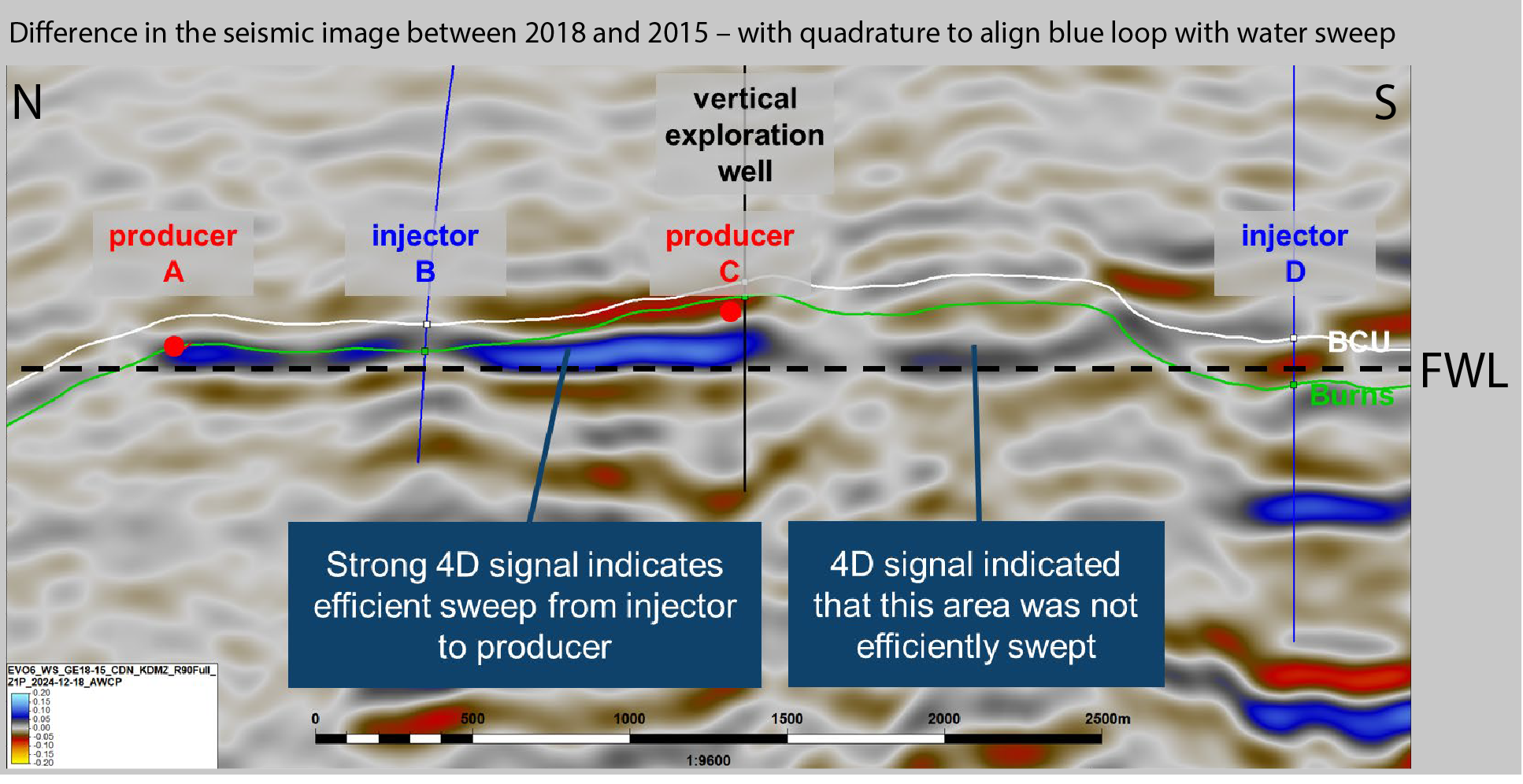

First of all, let’s look at an example of varying sweep efficiency in the Burns reservoir and how this is revealed by the 4D survey. Figure 1 shows the 4D seismic signal calculated between the 2015 (baseline) and 2018 (monitor) surveys. A few things stand out. There is a strong hardening effect between water injector B and producers A and C, which is indicative of water replacing oil (increase in AI). However, it can also be observed that the 4D signal is much weaker to the south of well C, leading to the interpretation that this part of the reservoir was not as efficiently swept. At the same time, the presence of a weak 4D signal indicates the reservoir is not completely tight; otherwise, no signal would have been observed at all. A subsequent infill well drilled between well C and D showed that this interpretation was correct, and it became the best producer in the field.

Another interesting observation from this seismic line comes from the injector well (B). In the vicinity of the well, at reservoir level, it can be observed that the 4D signal is dimmed, where one might expect a similar response to what can be seen a little further away. As Andrew clearly explained in his talk, the AI change is not only a result of an increase in AI due to water replacing oil, but also a decrease in AI due to a pressure increase in the local area to the injector. These components cancel each other out, resulting in a dim 4D response.

So, in one location, a dim 4D response indicated inefficient sweep and a good infill location, but in another area, a dim response results from efficient sweep plus pressure increase. Andrew asked: How can we tell the difference between these two scenarios, since only one of them would result in a good infill well? The answer was to look at not just 4D amplitude maps, but also 4D time shift maps and 4D character on seismic sections.

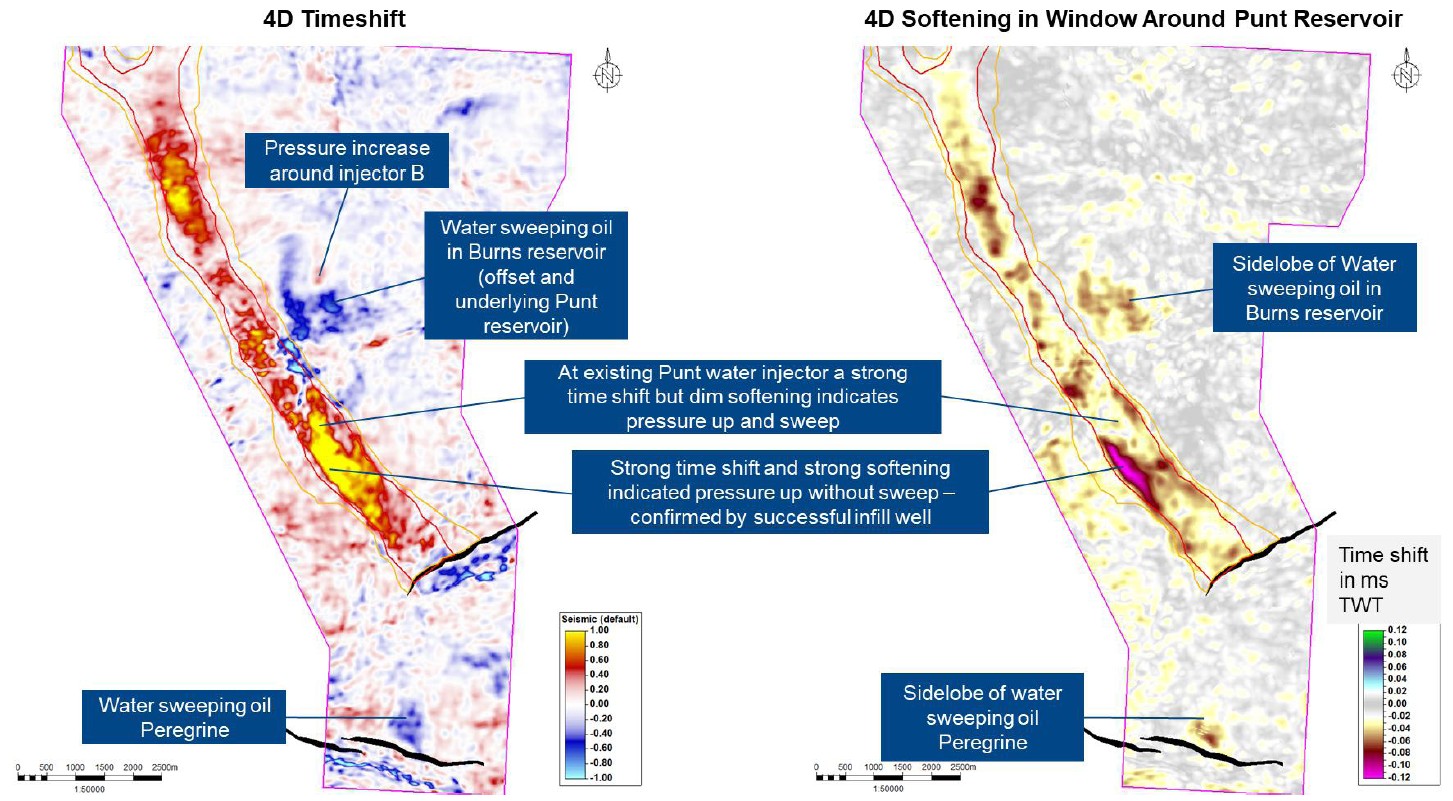

In the Burns reservoir, the sands are widespread and well connected, voidage replacement has been good, and pressure changes are small except very close to water injection wells. However, the Punt reservoir has a much longer and narrower geometry and has experienced large and widespread pressure changes.

Andrew presented a case in the Punt reservoir, whereby the question was asked: How can we recognise unswept areas that have experienced a pressure-up? A strong downward timeshift signal was observed in an area of the Punt, which indicates an increase in pressure resulting from water injection. The 4D amplitude change map is dim at the water injectors, but one part of this area of strong time shift also had a strong 4D softening signal. Together, this strong time shift and strong softening indicate pressure increase but an absence of water replacing oil, i.e. a region which is well supported by water injection but poorly swept. This area was subsequently targeted by another infill well, which confirmed the 4D seismic interpretation.

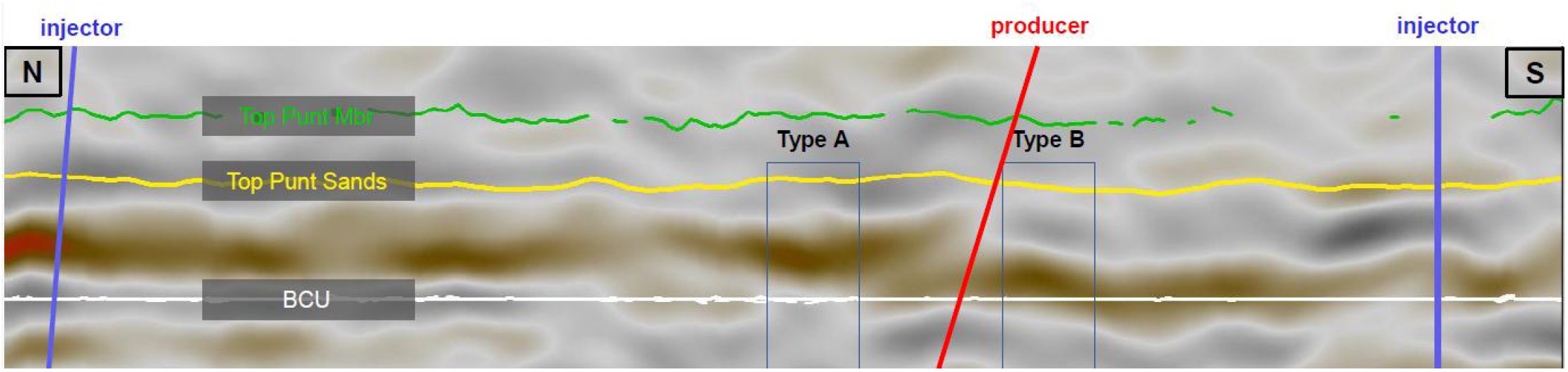

Andrew then continued to show another example illustrating a slightly more complex pattern of differential depletion and sweep in the Punt reservoir. As illustrated by the seismic line below, the observed 4D response on either side of the producing well is different. North of the producer, there is a broad red signal, whilst south of it, there is a blue-over-red signal.

In order to better understand the setting that could be responsible for these different patterns, the team created so-called “4D response panels”, which show the synthetic seismic 4D response for a variety range of sweep efficiency scenarios and pressure changes. This resulted in the observation that the broad red 4D signal corresponds to a poor sweep between 0 and 10 %, whilst the blue-over-red response is consistent with a 30-40 % sweep.

The examples shown here demonstrate that acoustic impedance changes can be caused by multiple factors, and that these all need to be assessed, together with the geology and field history, to make correct inferences on what a 4D signal really means. A dim area around a water injector could be well explained by a local pressure increase and a subsequent decrease in AI, balancing the increase in AI through water replacing oil. Taking these things correctly into account, the value of high-quality 4D cannot be easily overstated when it comes to planning infill wells in a mature field. One of the most important lessons is that a weak 4D signal may actually be a good sign for remaining oil; it shows that a connection does likely exist, but it may need another infill well to be exploited efficiently. A complete lack of 4D signal could be more risky, because it does not rule out the possibility that the lack of 4D signal results from a lack of reservoir at that location, not a lack of sweep. Both of those scenarios could be consistent with observing no 4D response.

Although all of the Golden Eagle infill well results were consistent with the observed 4D seismic, Andrew concluded that “4D seismic does not lie, but sometimes it does keep secrets”.

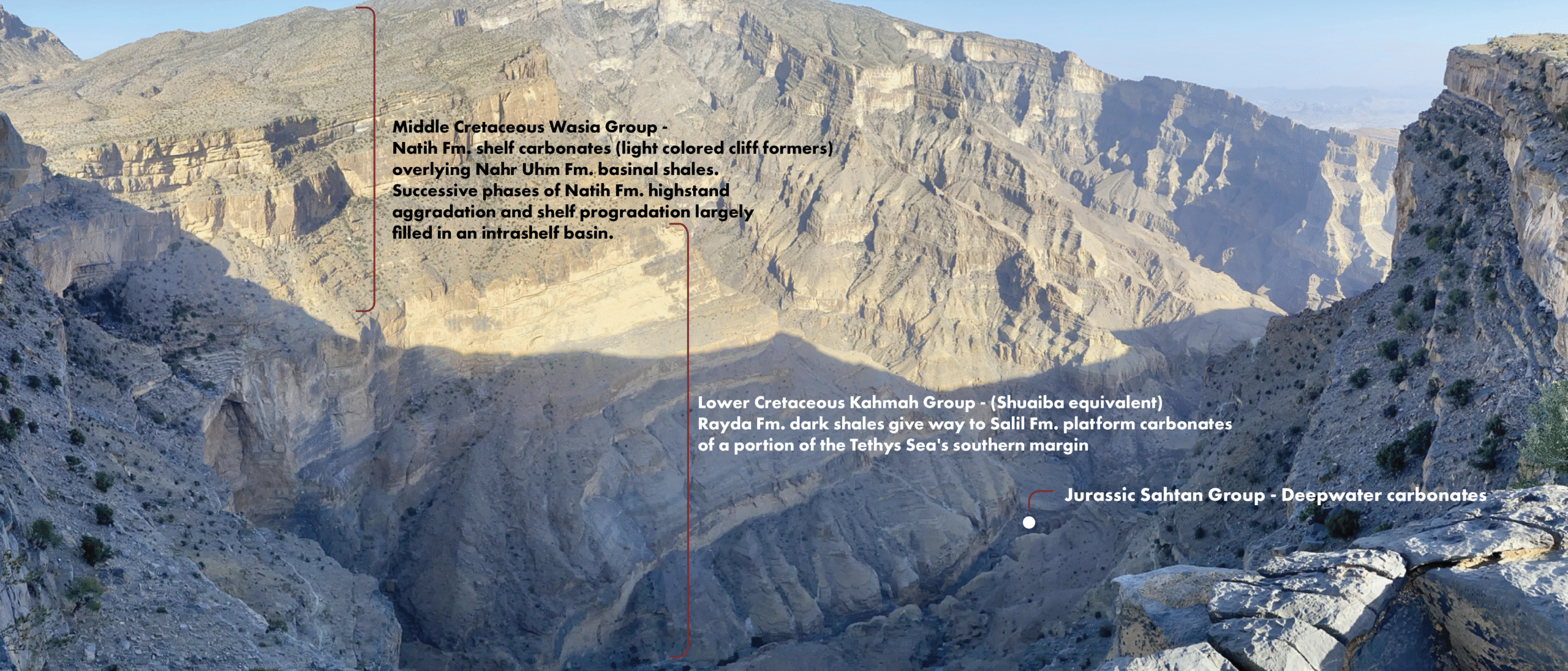

The Golden Eagle field was discovered in 2006, with first oil achieved in late 2014. The field has two main reservoir units, the Lower Cretaceous Punt and the Upper Jurassic Burns sandstone. The Punt is a relatively narrow and long submarine channel fill, whilst the Burns sands have a more widespread distribution with good aquifer support. Both fields have a combined stratigraphic, structural and fault trapping configuration. The recoverable volume of oil from Golden Eagle is expected to be 140 MMboe.