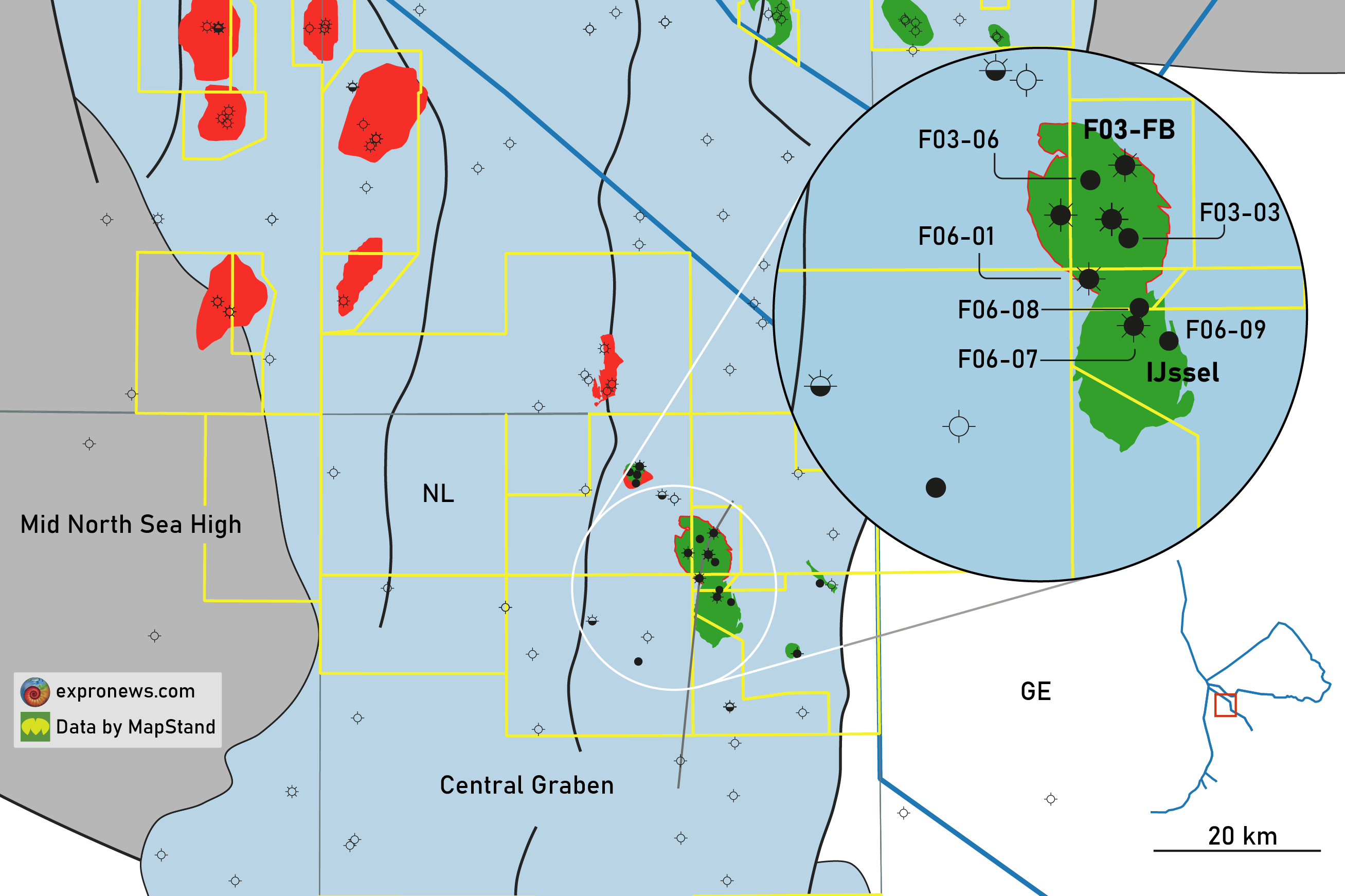

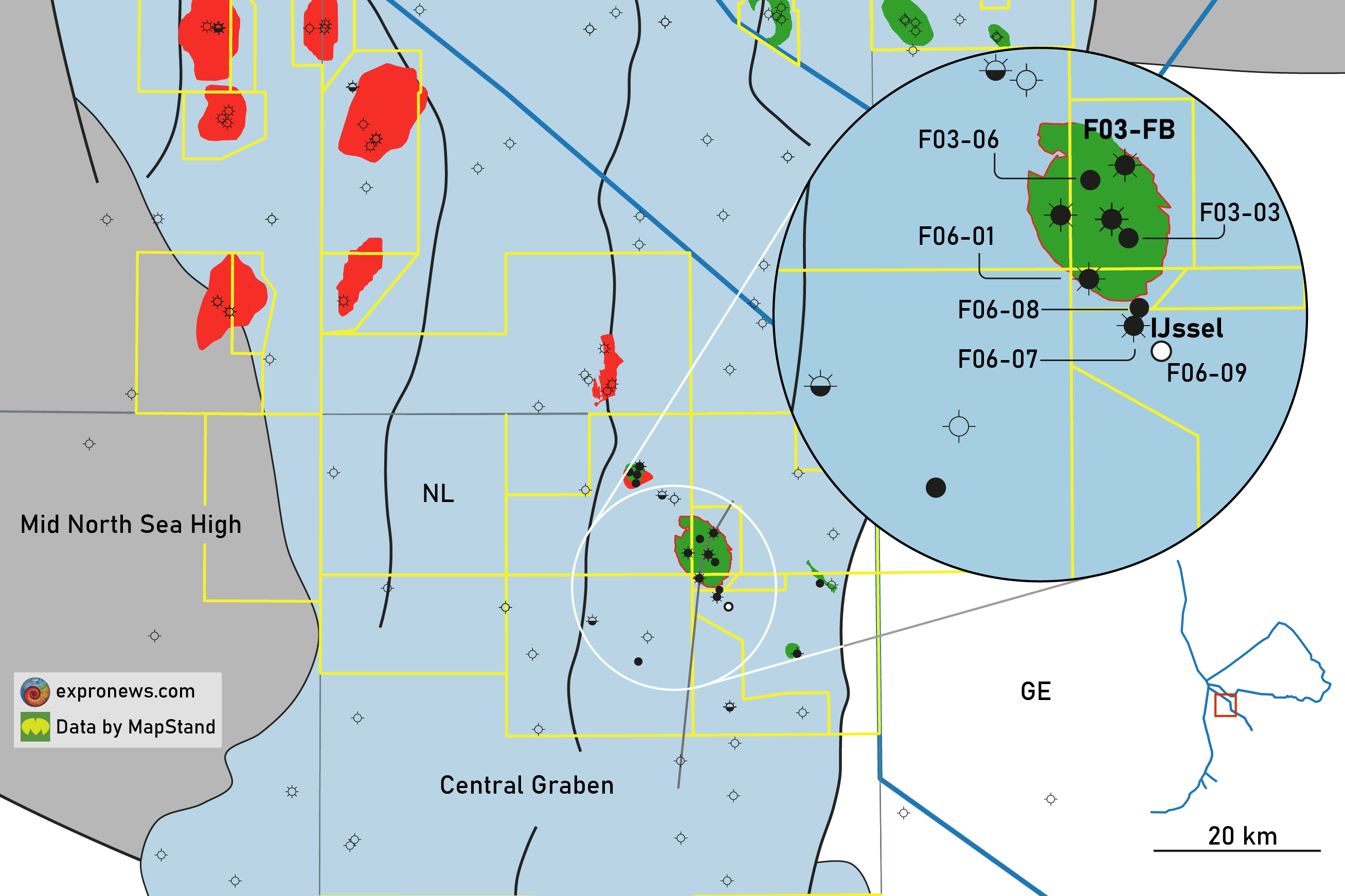

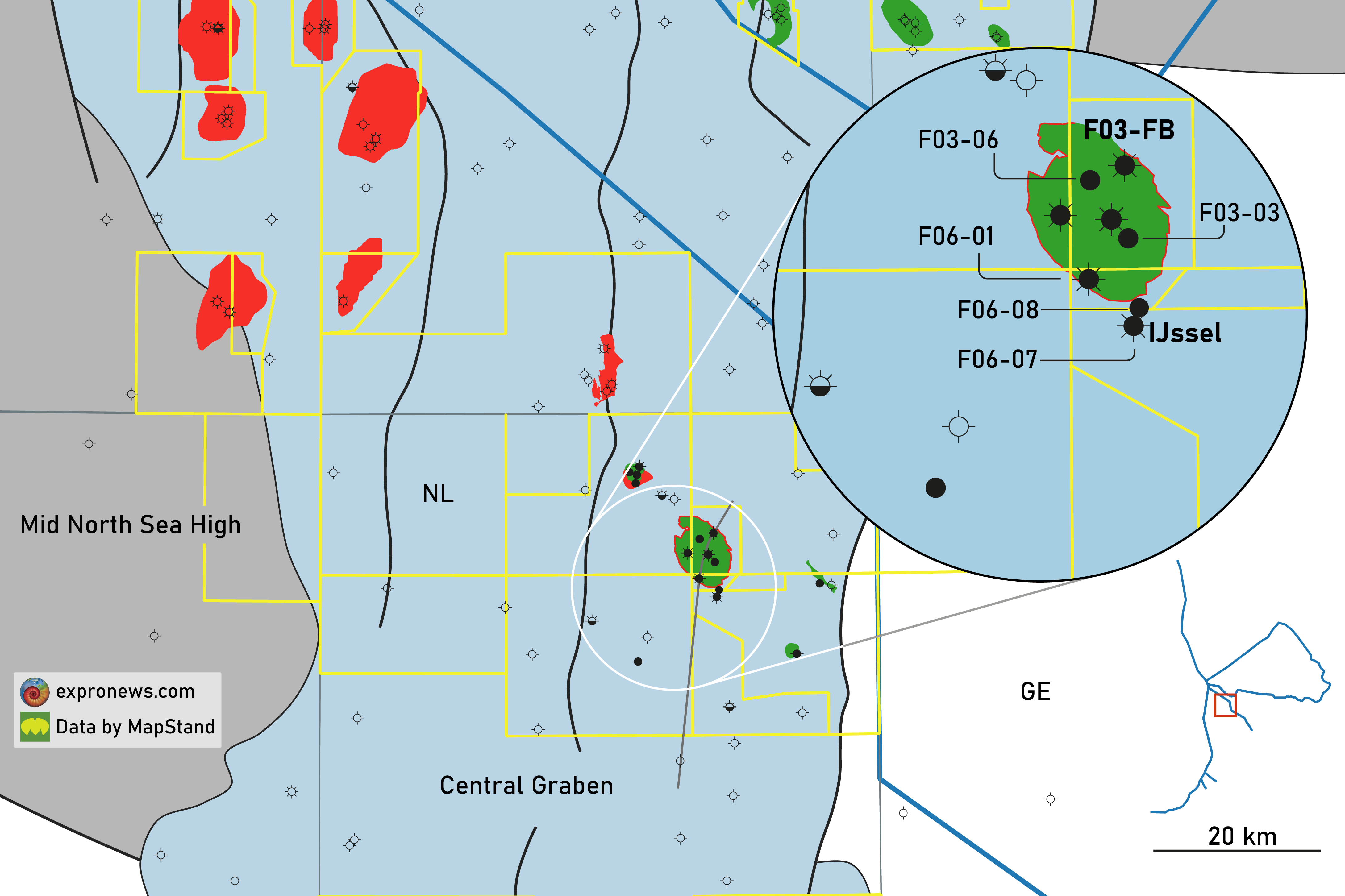

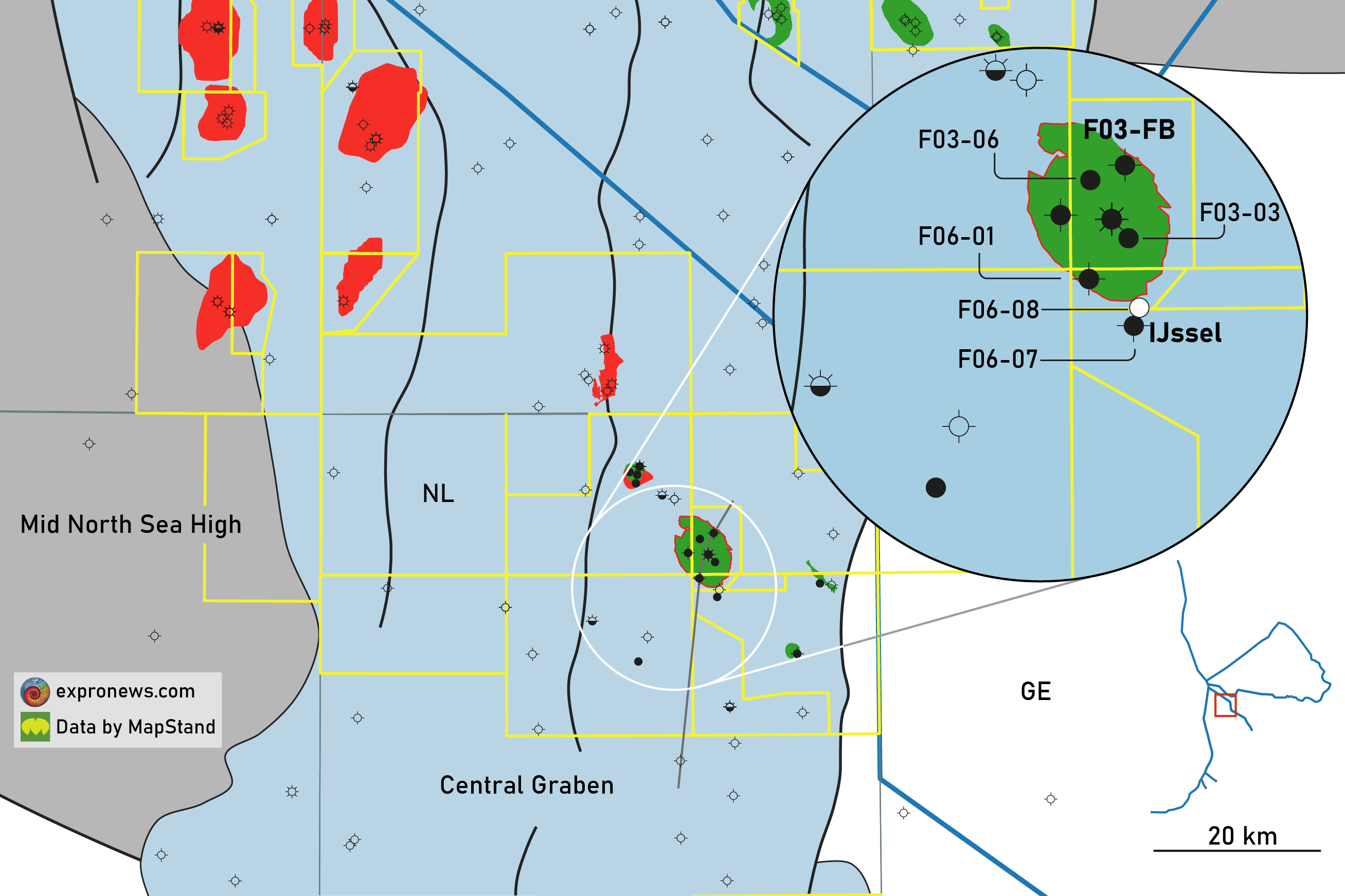

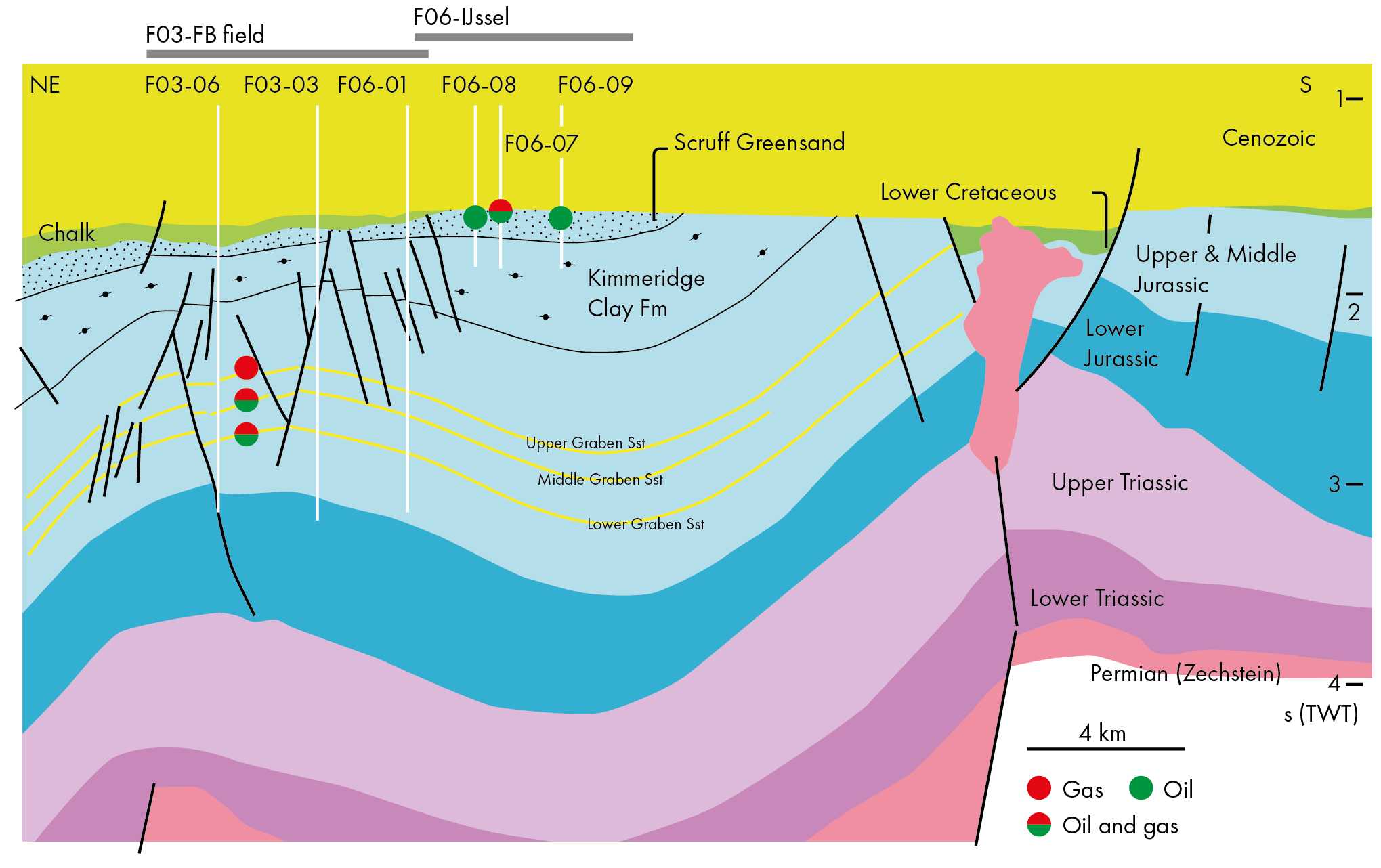

“It may be the last oil field development in the Dutch sector,” upstream analyst Bert Manders told me the other day. The IJssel field development in the northern part of the Dutch offshore, operated by ONE Dyas and partnered with Dana Petroleum, could indeed be the last oil discovery that will make it to first oil in the Netherlands. Only for that reason, it is worth writing an article about it. But there is another aspect that makes IJssel quite particular too, and that is the type of reservoir and the surprises it had in store.

IJssel is mostly reservoired in Upper Jurassic glauconitic sands of the Scruff Greensand Formation, deposited in a shallow marine environment. The difficulty with glauconite is that it has the physical characteristics of a sandstone but the chemical composition of a clay. Besides being a clay mineral, the glauconite grains themselves have a porous internal structure, adding up to a large portion of the total pore volume. Unfortunately, these grain-internal pores are micro-pores that hold capillary-bound water only, leaving no place for hydrocarbons. This is why water is more attracted to it than to “normal” sands, with the result that the derived water saturation log “reads” relatively high water saturations in glauconitic sands. In turn, that led to an initial placement of the projected Free Water level (FWL) at too high a level in the exploration well.

The tool that came to the rescue was the NMR tool, which is capable of differentiating between bound water and free water. The results from the NMR tool suggested that most of the water was bound, leaving room for another fluid to be in the macro-pores: Oil.

Then, it was also observed that oil shows had been made below the initially defined FWL, adding to the idea that there must be oil deeper down as well. This formed the basis to also test the formation below the FWL, with a very nice surprise as a result. As Rob Lengkeek presented at the Energy Geoscience Conference in Aberdeen in 2023, dry oil flowed at a stable rate from this newly and deeper perforated level.

This must have added the reserves to IJssel that made it worth pursuing with the development; ONE Dyas expects to produce almost 20 million barrels of oil from the field, as well as an additional 3.2 MMboe in gas over the course of 20 years, using four production wells and one water injector.

The last interesting thing about the IJssel discovery is that it is located very close to the F03B field, which has been producing oil and gas since 1994 from slightly older and deeper Upper Jurassic sands. The cross-section nicely shows how the F03B wells almost clipped the northern edge of the IJssel closure. It is not unlikely that the slightly “unconventional” behaviour of the glauconite-bearing reservoir forms one of the reasons why its potential was not realised until later on. But still in time for the field to be developed.