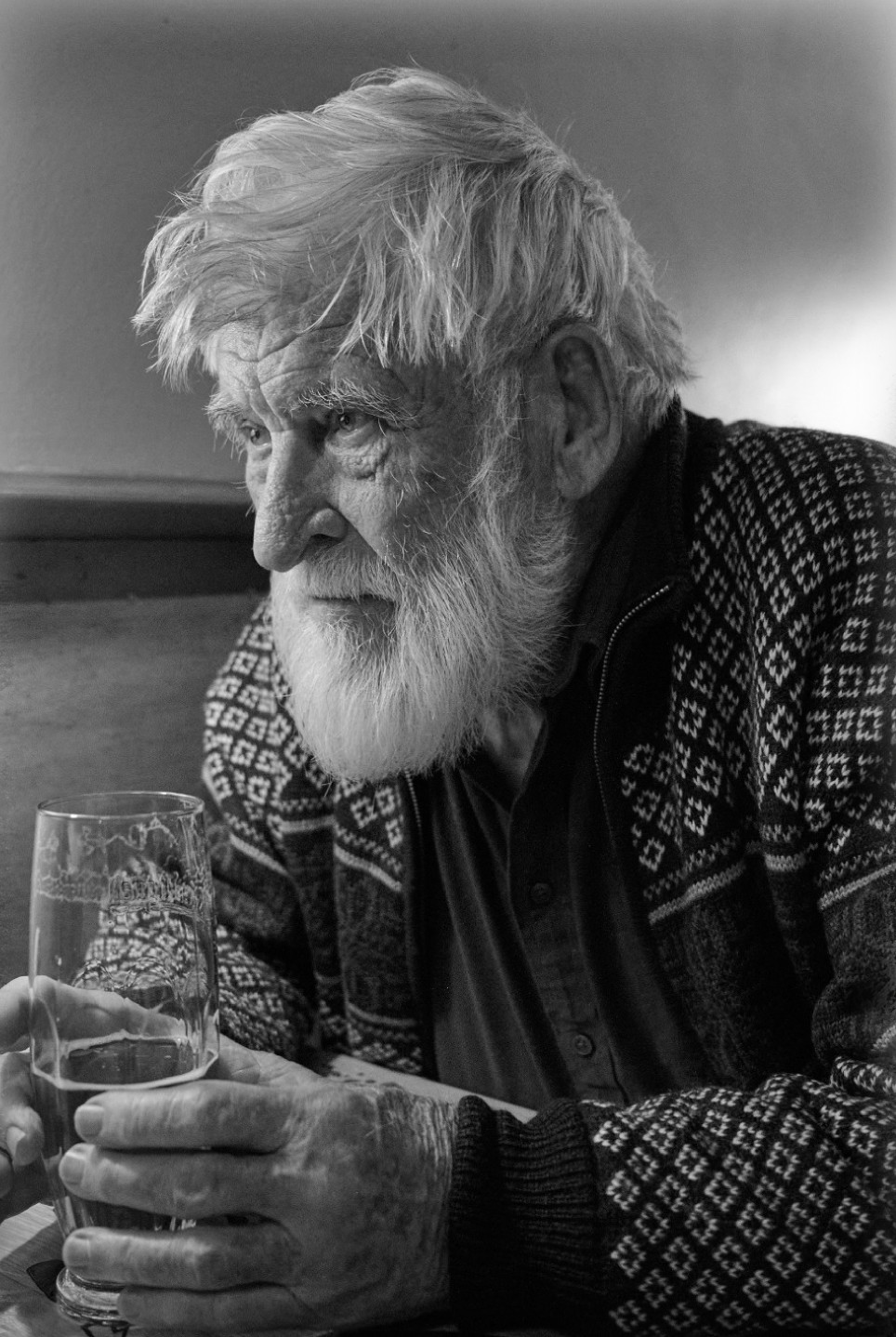

My father, 90, is a product of the random precariousness of this world. His mother’s first husband died at sea, washed overboard in a storm, whilst his father’s first wife and infant twins died of tuberculosis. Two tragedies not uncommon for that time. A widow and a widower picked themselves up and tried again – hence my father.

Why is this relevant to our oil and gas industry?

Well, I am an unashamed advocate for the oil industry. I have no qualms about what we do. In just one hundred years, hydrocarbons have made the world warmer, safer, and more reliable. I sit comfortably with Alex Epstein and his moral case for fossil fuels being the foundation of – and vital to – a modern, flourishing civilisation; and with the Czech Vaclav Smil whose more nuanced and empirical view holds that hydrocarbons are an essential resource to be valued, not wasted. We are now so much better at staying alive. Hydrocarbons have reduced the precariousness of this world.

But our industry is, by design, precarious. Oil and gas professionals know that better than anyone. There are current concerns about geopolitical instability, and how perceived weak or indecisive governments are killing the oil industry. That narrative seems to overlook two things: That business always blames government, and that the oil business has always been desperately unstable. Capitalism insists that the market is self-correcting and that only the weak are culled. But oil-price fluctuations kill companies; oil-price crashes kill communities.

Even when things are going well, there is uncertainty – lost careers and family sadness. Exciting new company mergers create redundancies, a euphemism for “discarded”. Twice in my career, I worked for companies that chose to relocate from London to Aberdeen. All very positive – unless you were a Londoner with kids at school and the grandparents around the corner. I wasn’t and didn’t, so I headed north – twice – but 90 % of the staff were not free and so were forced to choose: Unemployed or leave your life.

A consulting colleague recently said, “The difference between consultants and staff is that consultants know their tenure can end tomorrow”. Eventually, for some, it’s enough. I know plenty of people who have left the industry: Geologists to the civil service, a driller to defence, sports, to boatbuilding, to art, to e-gaming, to jewellery, to musical-instrument renovation, to market-gardening – on and on. All more stable. All happier.

My father-in-law was a pro-democracy agitator in communist Czechoslovakia. He would joke that Norway was “the last remaining communist country”. If that were true, then it is ironic and absurd that Norway has provided the most stable environment for oil-industry capitalism.

Václav Havel – Czech playwright and President – described hope as “not the conviction that something will turn out well, but the certainty that it makes sense, regardless of how it turns out”. In our oil industry, I doubt we have ever been able to expect either.