As the global energy transition accelerates, the demand for critical raw materials (CRMs) is rising at an unprecedented pace. The list of elements essential for modern technologies – from lithium and strontium to boron and rare earths – continues to expand. Yet, in the race to secure new sources, one unconventional domain remains surprisingly overlooked: Oil and gas wells.

It is increasingly clear that subsurface fluids long known for their hydrocarbon potential may also host valuable concentrations of dissolved CRMs. Elements such as lithium, strontium, boron, and bromine frequently occur in reservoir waters, sometimes in economical concentrations. With modern geochemical techniques, these brines can be re-evaluated not just as waste by-products, but as potential new revenue streams.

As both a geochemist and energy specialist, I have spent nearly a decade working at the intersection of petroleum geology and resource innovation. Among many experiences, one discovery stands out – a reminder that sometimes the past holds the key to the future.

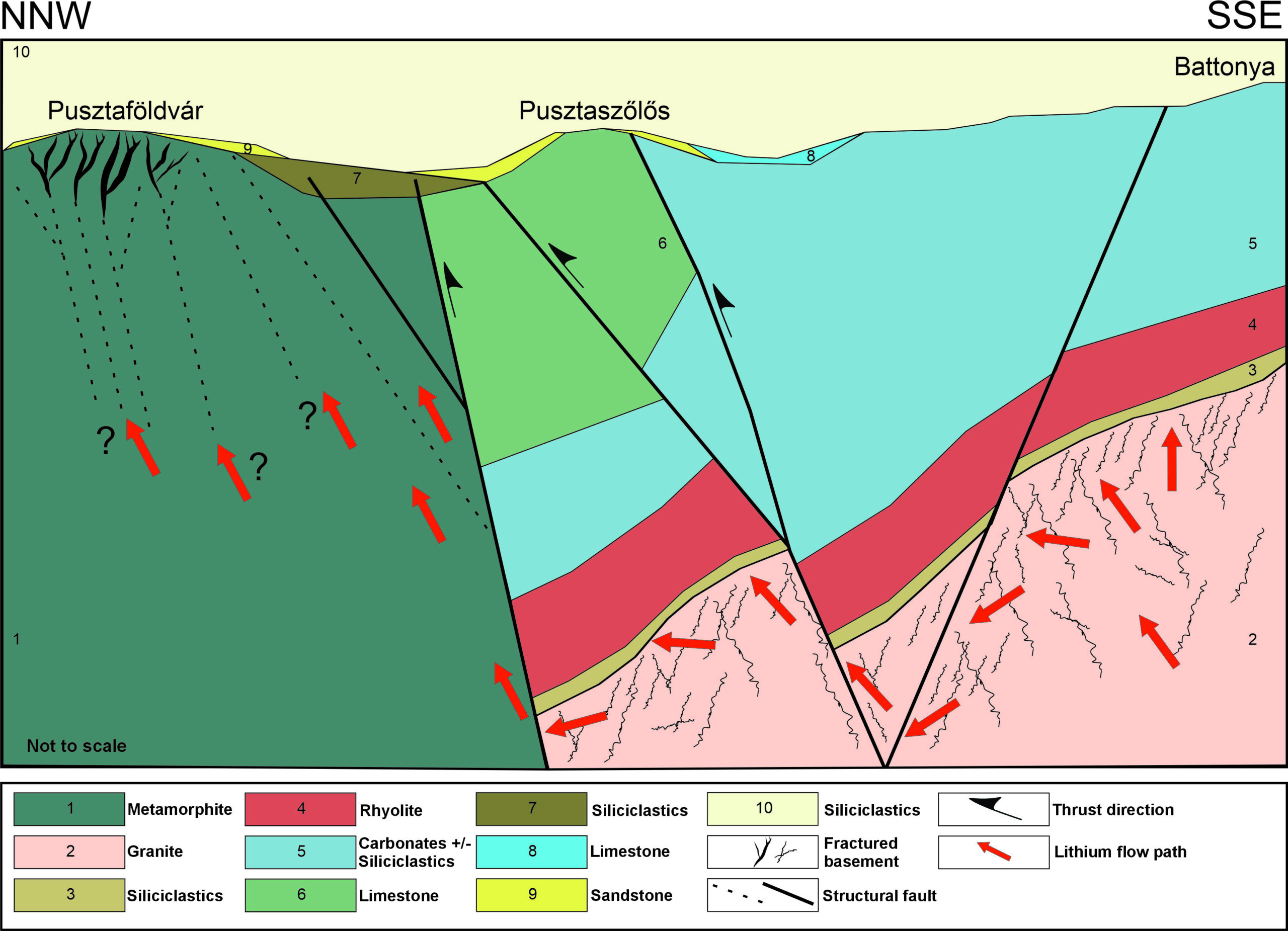

During a project revisiting historic oilfield data, I examined core samples from a 60-year-old development well in an overmature oil and gas field in southeastern Hungary. The well, the 80th drilled in the field, had long been forgotten – its data filed away after production began decades ago. The original core descriptions were brief and routine, noting fine-grained sandstones typical of the reservoir. Nothing appeared unusual.

That changed when we re-analyzed the core with modern mineralogical methods. To our surprise, nearly half of the rock’s mineral content was not quartz (SiO₂), but a lithium-bearing secondary mineral called cookeite. Cookeite is a Li-Al phyllosilicate, typically found in hydrothermally altered pegmatites and granitic systems – not in conventional oil reservoirs. Its presence indicated that lithium-rich hydrothermal fluids had circulated through this formation long after the reservoir formed. In other words, this “ordinary” oil well had intersected an unrecognized lithium-bearing system, hidden within the sedimentary sequence. Since then, more and similar features were observed in several other wells.

This finding was more than a mineralogical curiosity. It illustrated how legacy oilfield infrastructure can provide invaluable insights into the subsurface distribution of critical elements. With thousands of archived cores, water samples, and well logs available globally, the potential for discovering CRM anomalies within existing data is immense. By applying modern geochemical screening and isotopic analysis, old oilfield datasets could be transformed into CRM exploration tools, helping operators repurpose their geological knowledge for the low-carbon economy.

That old core taught me a simple but powerful lesson: Innovation often begins by re-examining what we think we already know. In the era of the energy transition, the boundary between hydrocarbon geology and critical mineral exploration is becoming increasingly blurred. Sometimes, the path to tomorrow’s resources begins with a second look at yesterday’s wells.